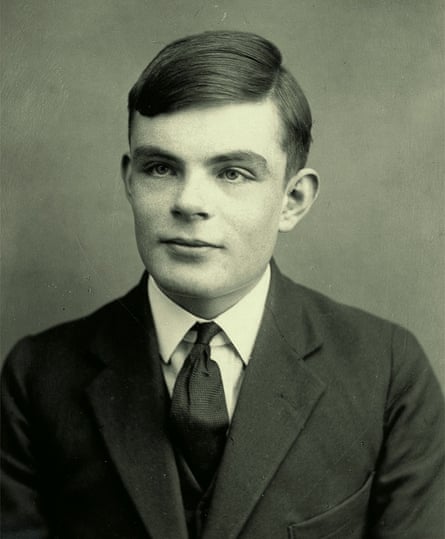

You don’t need a spoiler alert before being told how the Oscar-winning film, The Imitation Game, ends: mathematician and war hero Alan Turing was prosecuted for homosexual acts and, two years later, took his own life. In 2013, Turing was granted a posthumous royal pardon, but there are many more men whose lives were destroyed because of their sexuality, and who have lived with criminal records since.

The film inspired Matthew Breen, editor-in-chief of gay publication The Advocate, to set up a change.org petition demanding a pardon from the British government for 49,000 men convicted of consenting same-sex relations under the “gross indecency” law, 15,000 of whom are thought to be alive. A full-page advertisement in the Guardian in January, paid for by the movie’s producers, the Weinsteins, and signed by Benedict Cumberbatch and director Morten Tyldum, helped propel the pardon49k.org petition to over half a million signatures; it was delivered to Downing Street the day after this year’s Oscar ceremony by Turing’s family.

Last month, Liberal Democrat justice minister Simon Hughes said his party would demand a pardon in any coalition deal, though concerns have been expressed that a handful of paedophiles might slip through the net as a result. Campaigners say this could be avoided by introducing two amendments to current legislation: ensuring that the sex took place between consenting men, and that they were aged over 16.

While the 1967 Sexual Offences Act finally legalised homosexuality, it did little to end public and police persecution. According to research by campaigner Peter Tatchell into arrest figures during the 1980s, there were more than 20,000 convictions for the predominantly gay-related offences of gross indecency, soliciting and procuring. Entrapment was common, with police acting as agents provocateurs in public toilets.

All of this came to an end in 2003, with the repeal of the crime of gross indecency between men. In 2012, it became possible for those convicted of homosexual “sex offences” to have their criminal records erased under the Protection Of Freedoms Act – though not those deemed to have been committed in a public place such as toilets, where much of the entrapment went on.

The process is slow and often painful, however, and campaigners such as James Taylor, head of policy at Stonewall, want to see it simplified and extended. “There are still thousands of men out there who face difficulties because of convictions on their records,” Taylor says. “The fight for gay rights is not over.” These are some of their stories.

Stephen Close, 52, Salford

I joined the army in 1980 because I was confused about my sexuality. Coming from a deprived, working-class area, we had no education about things like that. I thought the army might make a man of me.

I was sent to serve in Berlin, where one of my jobs was guarding Rudolf Hess. He was one of the architects of the Final Solution, which included the imprisonment and murder of thousands of gay men. Ironically, a month later I was myself in a British prison for being gay.

I was 20 and I’d had a few drinks with another soldier one night. There was some chemistry there. We started kissing, but unbeknown to us, another soldier was watching. The following day I was on the firing range when two military policemen arrived. I was escorted back to camp, where they put the allegations to me. I denied it. After several days of constant questioning, I cracked. At that point, I was charged with gross indecency and sent for court martial. There was a lot of abuse from other staff and I was beaten up. All my army friends turned their backs on me. I suppose they were afraid. It was horrible.

I had no legal representation at the court martial. I was sentenced to six months in military prison and discharged with disgrace. I was then flown out of Berlin under armed escort and transferred to Colchester military prison, where I had to wear red ribbons on my uniform to signify my crime, so the guards could keep an eye on me. My mum and dad came to visit me in prison. They were very understanding, really.

I served four months. It wasn’t long, but I was in pieces. I broke down on the train home to my parents – it felt like my life was in tatters. I spent a lot of time in my old bedroom. I had suicidal thoughts, low self-esteem and no confidence.

When I was released, my father gave me a talk. He said: “Although we don’t have much money, we will find a way of paying for a cure.” I told him there was no cure and I had come to terms with what I am. My father embraced me and told me he still loved me.

Because of my record, I found it very difficult to get any decent work. I’d left a good job as an apprentice engineer to join up, too. In 2007, I had a job with a cleaning company and worked my way up to a supervising role. They won a contract to clean the local police stations, but that meant a criminal record check. I was told they wouldn’t give me clearance. I had to explain why to my manager and hand in my notice. I was angry and hurt again.

Then, in January 2013, two police officers came to my house demanding I go to the station to give my DNA or I’d be arrested. My mum was frantic, asking to know what I’d done wrong. It turned out to be part of Operation Nutmeg, in which criminals with convictions predating routine DNA collection could have theirs taken and added to the national database.

Afterwards, I sat in my car, devastated. All the life was sucked out of me. I couldn’t believe it was still haunting me after 30 years. Then Peter Tatchell launched a campaign and the DNA was destroyed. I applied to have my criminal record erased shortly afterwards, and eventually received a letter from the MoD saying my army record was now clear. There was no apology. It took a very long time to trust anyone, though I did go on to have two long-term relationships.

Now I want a pardon and an apology. Turing got one from Gordon Brown, but no one else has. It ruined my life. I have a poor job as a caretaker, no savings and no pension. I’m 53 and it’s too late to start a new career. All for a kiss.

Martin, 40, south London

In 1989 I was in my early teens and at secondary school in Kent, struggling to come to terms with my sexuality. I needed someone to talk to, so I confided in an English teacher. She asked if I was sexually active and, foolishly, I said I was. I expected advice, but instead my parents were informed and social services were brought in. Then the police became involved. They even used me in a covert operation, aimed at a local spot known for cruising. Fortunately, no one turned up, but my trust in everyone had evaporated. My school performance dropped and I left at 16, in 1991, with poor qualifications.

I’d wanted to be an electrician, but I ended up in a local department store. The owner made it clear he was aware of my sexuality from the off, so obviously the school had informed him when he asked for a reference.

Not long after, I met a lad my age in the park. I was relieved to find someone I could relate to. We saw each other a few times, then one week he wasn’t there. I was disappointed, because I’d hoped we could have a relationship. A few weeks later, just after my 17th birthday, I was called into the boss’s office. Two policeman arrested me and I was taken out in handcuffs in front of everyone. At the station, I was left in a cell for hours. I asked for a solicitor, but was told one wasn’t available.

When I was questioned, it transpired the boy I’d met was 15. It was a shock. I hadn’t asked, and it wasn’t as if he was in school uniform. In fact, I thought he was older than me. Nothing very sexual had gone on anyway, and at the time of our meetings there was a matter of months between us; we were both under the age of consent. A boy and a girl so close in age would not have been arrested.

When the indecent assault charges were read out in court, they had added “attempted buggery” to the list. I hadn’t done any such thing, nor was it on the original charge sheet. I had no legal advice to stop it. I was sent for trial at crown court and bailed.

That week I opened the local paper and there was my picture, coming out of court that day, along with some other people, and a story about a paedophile ring. I’d never seen any of them before. When I went back to work, I was attacked. Eventually, thankfully, a solicitor got the buggery charge dropped, but I was found guilty of gross indecency and indecent assault, and given two years’ probation.

I left the store, but it was hard to find work because of my criminal record. I got a job in a warehouse, then someone from my old school arrived and told everyone. I wasn’t taken on after my probation. I began to suffer from depression. I lost self-esteem and became increasingly careless about my own safety. In 2000, I was diagnosed HIV positive. I would have killed myself without the psychiatric help I got as a result of that.

The Turing petition has highlighted what went on in this country. An apology might help me move on, but it won’t make me HIV negative. Nothing will take away the pain I’ve suffered.

Today, I’m living in a council flat on benefits that the state are trying to stop. I’m studying so I can be an electrician, but I refuse to take a poorly paid job. Why should I, after everything? I’d rather die.

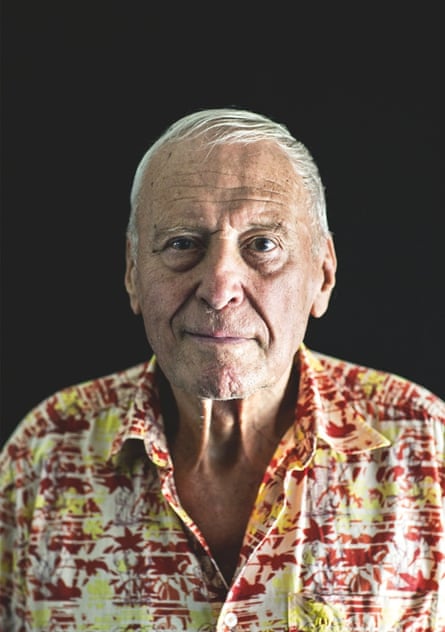

George Montague, 91, Brighton

After the war, I lived in a small village called Hitcham in Buckinghamshire, where I ran an engineering business employing 40 people. I was a scout commissioner and a pillar of the community.

In 1974, when I was 50, I went to Slough for the day. There was no one else of my persuasion in Hitcham, so I used to go looking for company. There was no internet or gay scene, and hardly any bars, so we used to gravitate to “cottages”, or public toilets.

The place was empty but for one man in a cubicle. I went into the adjoining cubicle and locked the door. There was a hole in the wall between us, a sure sign it was a gay haunt.

I had a glance through and the chap was much older than me. I blocked up the hole and waited for him to go, but instead he pushed the paper out and attempted to put his penis through. At that moment there was a scuffling outside and a police officer craned over the top of the door. I was doing nothing; I hadn’t invited any contact from the other man, but the timing was awful. We were both arrested and taken to the police station.

During questioning, they produced a “queer list” with my name on it. They made it their business to find out the name of anyone locally who was gay. They’d do it by arresting a young gay boy and threatening him until he gave them as many names as possible. I was charged with gross indecency and sent for trial. I employed a solicitor and counsel, which cost a lot of money, and pleaded not guilty.

A friend, a local doctor, went before a jury for a similar offence and was found not guilty, but it didn’t matter, because all the details came out anyway. The story was in the press regardless. It ruined him and he died a broken man. The man in the adjoining cubicle to me pleaded guilty, which, I suppose, he was. That was also all over the papers – that he was a married man with children. The disgrace for many men was terrible.

There was no story about me, despite me being found guilty. I had a few contacts on the local paper because of my community work, and they were kind. There was suspicion in the scout movement, though, which made me angry and upset. I know the word “paedophile” was used, and that was humiliating. I resigned, which hurt a great deal.

I was fearful it would come out, though. My wife knew I was gay when she married me – she was a wonderfully supportive woman – but no one else knew: not friends, not my children. I took it in my stride. I came to terms with it, and had several relationships subsequently. Today, I live with my long-term partner of 18 years.

I was lucky, really, compared with some, but I remain very angry about what happened to me. I served my country during the second world war. I don’t want a pardon because I’m not guilty. I’m angry with the government and the entire establishment throughout the 20th century. They need to apologise to the gay community on behalf of their predecessors, and the police need to apologise for the way they enforced the law. There are many men out there with this stigma hanging around their neck.

Peter, 57, north London

I was 21 in 1979, when I was caught, entrapped, in public toilets, twice in one year.

The first time, I went into a toilet in Stockport and stood at the urinal nearest the door. A man at the far end kept staring at me. Then he moved one cubicle closer. At that moment, two policeman shot out of the washroom behind us, and we were arrested and taken to the station. I protested that I hadn’t done anything, but they said they’d seen us and that the other man had an erection, which was untrue. I was charged with soliciting and released.

I went home pretty fearful and looked up a solicitor in the Yellow Pages. When I explained what had happened, he asked if I was gay. When I said I was, he said, “Just plead guilty.” I did as I was told, and was given a £100 fine and a criminal record.

The following day, to my horror, it was the front page of the Manchester Evening News. People at work knew I was gay, but it was hugely embarrassing. I was far more worried about what my parents would say. My dad was very traditional, captain of the local golf club, that sort of thing. To this day, it’s never been discussed.

Six months later, I went into a public toilet in Manchester city centre. I was in a rush, but I noticed a pretty guy stood in a urinal a few places along. His face was very flushed. He kept looking at me, giving the impression he was masturbating. As I glanced at him, another man entered the toilet, walked behind us, then walked straight out. When I left, he was waiting outside. He stopped me and arrested me for soliciting. The young guy came out and turned out to be a policeman. Nothing sexual had happened, but they both testified I had an erection, which was, again, totally untrue. I was taken to the station, where the conviction from earlier in the year inevitably came up: “You’ve got a record for this sort of thing, haven’t you?”

I couldn’t believe it. I was charged and let go. I found another solicitor, whose advice was the same: plead guilty. In court, I was given a heavier fine and another conviction for a sexual offence was added to my record. This time, the story only made page three of the Manchester Evening News.

People will wonder why I didn’t make more of a fuss at the station, but Manchester was a very precarious place for gay men back then. I had first-hand experience of their hypocrisy even before those two incidents.

When I was 18, I was walking home from a gay bar when an older man attacked me under a railway arch and raped me. He was huge and I couldn’t fight him off. I agonised about it for a few days, then decided to report it, so I went to the local police station. As I approached, the desk sergeant looked up from his pad: it was the man who had raped me. I turned around and ran out.

I got over what happened reasonably well. Last year, I married my long-term partner and I have a decent job where no one cares that I’m out. But I’m still angry about what happened. I don’t want a pardon, because I didn’t commit an offence. I want an apology and I want these convictions taken off my record, although I don’t hold out much hope.

Richard, 69, Warwick

I grew up in a small mining town in Staffordshire. In 1962, I was 16 and had just left school to go to college. It wasn’t the sort of place where you acted gay if you had any sense, so you looked for a cottage. I met a few local lads that way. Then we met an older guy in his 40s who had a car.

There was no grooming, but one of the boys let it slip that he had been with another lad, and his parents reported what was going on. I was stopped in the street one day and taken to the station. Once they had me in there, I was told that the others had confessed to having sex, which turned out to be untrue. I was terrified. They had to bring my father in. He got hold of a solicitor, who was useless. As the pressure built, he didn’t stop me from talking. He was more like, “Get it off your chest.” I was asked if this older guy was involved. I said yes and he was arrested, too. We were all told to plead guilty. The older guy pleaded not guilty and was found not guilty.

I went before a magistrate and was remanded in custody, on the basis I might reoffend. I can recall the disgust on the magistrate’s face. I was in tears and no one from my family was there to help. A black maria came and I was taken to Winson Green prison to await sentence.

There was no induction wing, so I was put among the men. I appealed on the basis that the older guy had been found not guilty, so I couldn’t have done anything, either. It was thrown out and I was sent to borstal. It was complete summary justice.

I was taken to Shrewsbury prison and then moved to Wormwood Scrubs, which was the holding prison, while they waited for a place at Feltham Young Offenders. I was in the Scrubs for a month before I finally moved to Feltham, where I was put in a separate unit with about 100 others, all in single rooms because of our status. About 70 or 80 of us were in for homosexual offences, the rest were rapists and the like.

I was in there for about 15 months, on top of the three I’d served on remand. It was tolerable. I wasn’t beaten up, fortunately. My family came to visit once. Inside, I had a job as a carpenter’s assistant with a member of staff who used me for sexual favours and paid me in tobacco.

When I got out, I returned home for a while, but I hardly ever went out – I was too scared. Eventually, I left and moved to Birmingham. My relationship with my parents never recovered.

I’ve buried what happened to me, but the scars are there. Only a few people know what happened, and there’s always that fear of being exposed. My ex-wife knew, because I’m bisexual, but my kids don’t.

I don’t feel sorry for myself, but I do feel sorry for the men who killed themselves because of their treatment. I didn’t know I could have my conviction quashed until now, and I’m going to apply. I believe there should be a pardon for all those treated so badly. I can forgive my parents for what happened, but I’ll never forgive the police and the justice system. Some names have been changed

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion