Google, and its parent company Alphabet, has its metaphorical fingers in a hundred different lucrative pies. To untold millions of users, though, "to Google" something has become a synonym for "search," the company's original business—a business that is now under investigation as more details about its inner workings come to light.

A coalition of attorneys general investigating Google's practices is expanding its probe to include the company's search business, CNBC reports while citing people familiar with the matter.

Attorneys general for almost every state teamed up in September to launch a joint antitrust probe into Google. The investigation is being led by Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton, who said last month that the probe would first focus on the company's advertising business, which continues to dominate the online advertising sector.

Paxton said at the time, however, that he'd willingly take the investigation in new directions if circumstances called for it, telling the Washington Post, "If we end up learning things that lead us in other directions, we’ll certainly bring those back to the states and talk about whether we expand into other areas."

Why search?

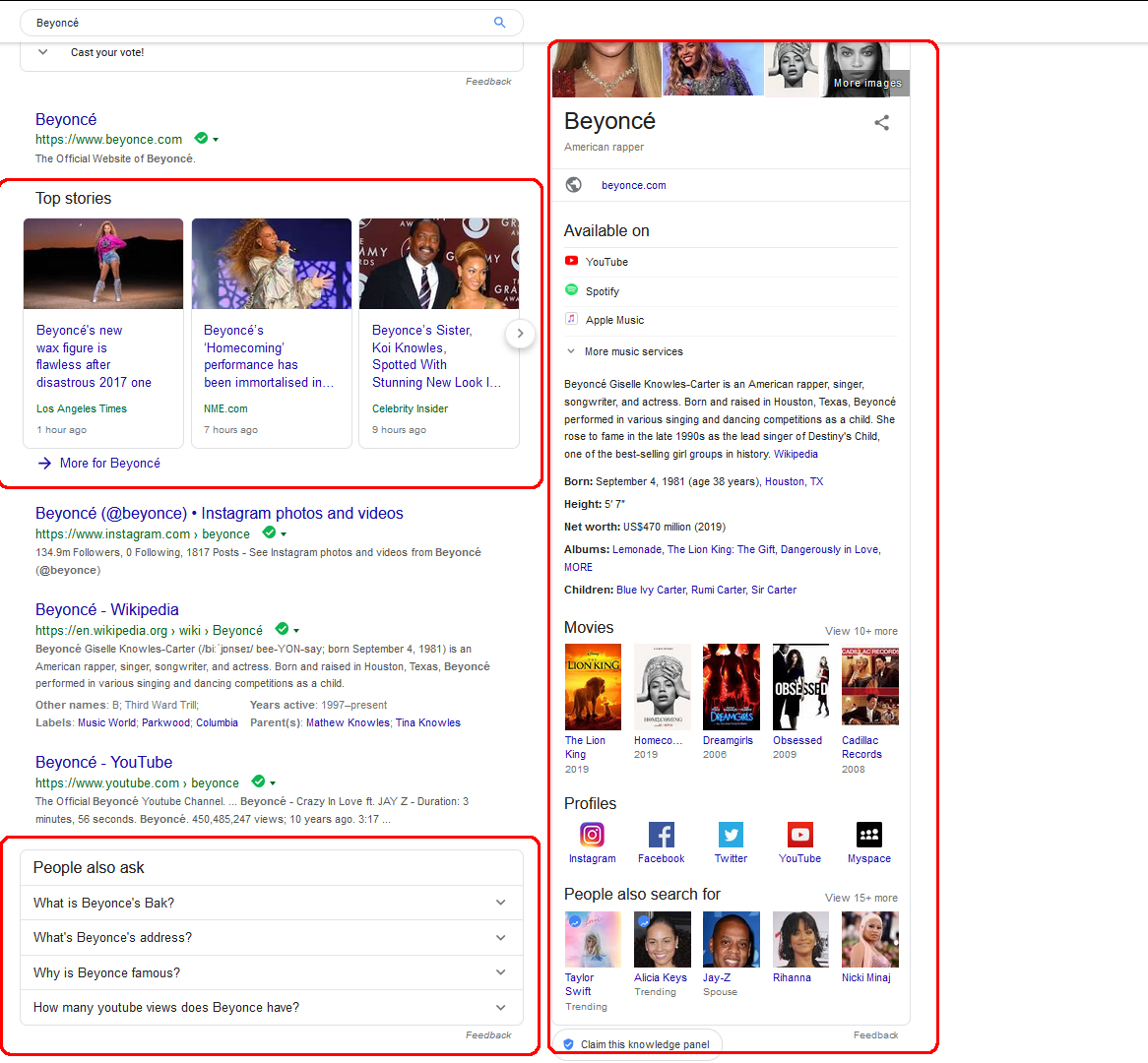

Google's decades-long dominance in the search market may not be quite as organic as the company has alluded, according to The Wall Street Journal, which published a lengthy report today delving into the way Google's black-box search process actually works.

Google's increasingly hands-on approach to search results, which has taken a sharp upturn since 2016, "marks a shift from its founding philosophy of 'organizing the world's information' to one that is far more active in deciding how that information should appear," the WSJ writes.

Some of that manipulation comes from very human hands, sources told the paper in more than 100 interviews. Employees and contractors have "evaluated" search results for effectiveness and quality, among other factors, and promoted certain results to the top of the virtual heap as a result.

Loading comments...

Loading comments...