It's hard to have a meaningful discussion about Apple Pay (iOS' most recent foray into mobile payments) and Google Wallet (Android's three-year-old platform that's had tepid success) without talking about how the systems actually work. And to talk about how those systems work, we have to know how credit card charges work.

It seems like a simple thing, especially in the US—swipe your card, wait a second or two for authorization, walk out of the store with your goods. But the reality is that a complicated system of different companies handles all that transaction information before your receipt ever gets printed.

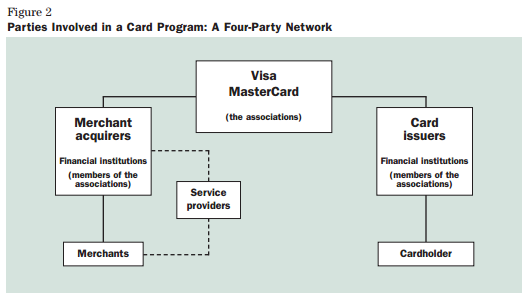

The four-party system

If you're using a so-called “universal” card like Visa or MasterCard, there are typically four parties involved: the merchant, the payment processor, the merchant acquirer, and the issuer. Their roles are as follows:

- The merchant is the person offering goods or services that you (the customer) want to buy.

- The card issuer distributes cards to customers, extends lines of credit to them in the case of credit cards, and bills them.

- The merchant acquirer signs up merchants to accept certain cards and routes each transaction to the card network's processor.

- The processor then sends the transaction information to the correct card issuer so the funds can be taken from the customer's account and delivered to the merchant.

Visa and MasterCard are considered card networks in all of this. And as umbrella organizations, card networks aren't explicitly counted in that four-party system, but they facilitate the system's operation and often have ties to other parties involved.

MasterCard SVP & Group Head for Digital Channel Engagement Sherri Haymond explained the company's role to Ars. "MasterCard sits in the middle: we have a franchise that financial institutions apply to join," she said. From MasterCard's perspective, "acquirers bring merchants into the system, and issuers bring consumers into the system. MasterCard's role is to set rules and standards, and we facilitate movement of money, in most cases from the issuer to the acquirers."

For our purposes, we'll look at Visa- and MasterCard-like relationships, specifically. Just know that some companies—like American Express, Discover Card, and Diners Club—can play the role of the card issuer and merchant acquirer at the same time. And cards issued by companies like Macy's or Sears will likewise have a somewhat simpler system behind the transaction, because these “private label” cards are generally only accepted by one merchant.

Of course, things aren't always so straightforward in practice. According to a paper written by Ramon P. DeGennaro for the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta [PDF], “The payment card industry comprises many different entities that perform various tasks, and because many of them have formed alliances, the lines between them are often blurred.”

DeGennaro writes that the most important institutions in this four-party system are the merchant acquirer and the payment processor. Despite their importance, customers often never interact directly with these two entities. The functions of acquirers and processors can be performed by the same company, although many acquirers usually re-sell the services of a third-party processor.

What happens when you buy something

When a transaction takes place, two major processes occur: the card gets authorized, and the transaction is then cleared.

DeGennaro describes the authorization phase best:

The terminal sends the merchant’s identification number, the card information, and the transaction amount to the card processor. The processor’s system reads the information and sends the authorization request to the specific issuing bank through the card network. The issuing bank conducts a series of checks for fraud and verifies that the cardholder’s available credit line is sufficient to cover the purchase before returning a response, either granting or denying authorization. The merchant acquirer receives the response and relays it to the merchant. Usually, this process takes no more than a few seconds.

Once the card has been authorized, the second part of the transaction is clearing it, or getting the goods to the customer and the money to the merchant's bank. The merchant sends transactions to the merchant acquirer, and the merchant acquirer sends that information along to the merchant accounting system, or MAS, that supports an individual merchant's account. DeGennaro says that the distinction between the merchant acquirer and the MAS can be muddy. "In some cases, the MAS is a part of the merchant acquirer; in others, it is a different entity." DeGennaro continues:

The MAS distributes the transactions to the appropriate network—Visa transactions to the Visa network, MasterCard transactions to the MasterCard network, and so forth. Next, the MAS deducts the appropriate merchant discount fee (to cover the costs of the merchant acquirer’s activities) from the transaction amount and generates instructions to remit the difference to the merchant’s bank for deposit into the merchant’s account. The MAS sends these instructions to the automated clearinghouse (ACH) network, which is a computer-based system used to process electronic transactions between participating depository institutions.

Merchants typically pay what is called a Discount Rate and a Transaction Fee, which are tied to what is called an Interchange Fee, which is determined by the payment card network (again, Visa or MasterCard). According to a Quora post by CEO of 1st American Card Service Brian Roemmele, republished on Forbes, 85 percent of this Interchange Fee is paid to the card's issuing bank (like Chase, or Bank of America, for example). These fees usually amount to about two percent of the purchase price on credit card purchases and are a profit driver for the issuing bank. They also help cover fraud costs and fund reward programs.

This system is complicated, and it is growing increasingly fraud-prone, especially when card information is stored on a merchant's terminal or is sent insecurely. To keep this article (relatively) short, we won't discuss Card Not Present (CNP) transactions, which usually occur online or over the phone and require a customer to input her or his card's security code (those digits on the back of the card).

In a quick note, however, because CNP transactions are much less secure than transactions where the card is present, CNP transactions usually demand higher Interchange Fees from merchants. But although NFC transactions on an Apple Pay or Google Wallet-enabled phone don't physically require a card to be present, they transmit information as if the card was present, so fees aren't higher for merchants that choose to enable NFC on their terminals.

The little-known Google Virtual Wallet Card

The important thing to know about Apple Pay and Google Wallet is that neither payment platform was first to develop tap-and-pay transactions. In fact, a number of stakes holders, especially Visa and MasterCard, had been doing research and development, running pilot programs, and issuing contactless payment-capable credit cards for years by the time Google Wallet entered the scene in 2011. MasterCard, especially, with its growing PayPass platform, had been working with retailers to make RFID, and later NFC (Near-field Communication) chips—which allow two-way communication between the chip and the terminal—readable by terminals at major retailers like Macy's, Whole Foods, and McDonald's.

That said, Google Wallet was the first major deployment of a mobile phone-based NFC payments system. When it debuted, Google Wallet was only available on the Sprint Nexus S 4G, and its official partners were MasterCard and Citi Bank. You could also buy a prepaid card through Google. With its limited number of partners, Google originally stored credit card information directly on the phone's Secure Element—an isolated chip in the phone that has very limited interaction with the rest of the phone's OS. When the phone came close to an NFC reader, Google required a four-digit PIN to be entered before the chip transmitted the card information to the terminal. Since 2014, Google no longer uses a Secure Element, instead relying on Host Card Emulation, which makes it easier for third-party app developers to take advantage of Android phones' NFC capabilities. Four-digit PIN authentication is still required for payments to take place. From there, the transaction proceeds as any normal credit card interaction would. With the four-digit PIN, users are prevented from, say, accidentally buying something.

But the small number of partners made Google Wallet adoption stall. In 2012, the company tried to bring more users into the fold by issuing an update that permitted “all credit and debit cards from Visa, MasterCard, American Express, and Discover” to be uploaded to Google Wallet's cloud-based app. That didn't mean that Google developed partnerships with these companies necessarily (American Express notably balked at the announcement), but Google's new scheme opened the payments system up to greater mobile payments adoption than ever before. That scheme, which remains intact as per Google Wallet's Terms of Service (TOS), last updated in July 2014, is facilitated by issuing the customer a Google Wallet Virtual Card. This Virtual Card is issued by Bancorp Bank through Google, and it essentially acts as an intermediary between the customer's preferred card and the merchant.

reader comments

98