The visitors started coming in 2013. The first one who came and refused to leave until he was let inside was a private investigator named Roderick. He was looking for an abducted girl, and he was convinced she was in the house.

John S. and his mother Ann live in the house, which is in Pretoria, the administrative capital of South Africa and next to Johannesburg. They had not abducted anyone, so they called the police and asked for an officer to come over. Roderick and the officer went through the home room by room, looking into cupboards and under beds for the missing girl. Roderick claimed to have used a “professional” tracking device “that could not be wrong,” but the girl wasn’t there.

This was not an unusual occurrence. John, 39, and Ann, 73, were accustomed to strangers turning up at their door accusing them of crimes; the visitors would usually pull up maps on their smartphones that pointed at John and Ann’s backyard as a hotbed of criminal activity.

John’s grandfather had bought the three-bedroom home in 1964 in a quiet, sedate neighborhood then popular with civil servants, and planted nectarine and peach trees in its large backyard. For the first 50 years, everything was more or less fine.

Ann and her husband inherited the home in 1989, and, as violence and crime rose in the area, they installed a fence around the property and bars over the windows. In 2012, John moved in, shortly before his father died. Unfortunately, that’s around the same time the problems started.

“My mother blamed me initially,” said John. “She said I brought the internet into the house.”

The visits came in waves, sometimes as many as seven a month, and often at night. The strangers would lurk outside or bang on the automatic fence at the driveway. Many of them, accompanied by police officers, would accuse John and Ann of stealing their phones and laptops. Three teenagers showed up one day looking for someone writing nasty comments on their Instagram posts. A family came in search of a missing relative. An officer from the State Department appeared seeking a wanted fugitive. Once, a team of police commandos stormed the property, pointing a huge gun through the door at Ann, who was sitting on the couch in her living room eating dinner. The armed commandos said they were looking for two iPads.

“It’s almost with religious zeal that these people come, thinking their goodies are in my yard,” John told me. “The Apple customers seem to be the worst.”

They wondered if it would be worse if they weren’t white South Africans. And indeed, when the police showed up looking for a stolen laptop at the home of their neighbor, a pastor named Horace, who is black, the police wound up seizing a laptop at the home and taking Horace’s tenant to the station for questioning. It was a dead end, as usual.

A few months ago, John received a legal complaint in the mail from a South African leather-goods shop called Benna Bok; the owners accused him of bullying them on Facebook and said they were frightened for their lives. That was the final straw. John got serious about figuring out what was happening and sought out experts who could help him. It’s also when the problem started costing him serious money; he hired a law firm, to which he’s paid 20,000 ZAR (or about $1,500) so far.

Despite appearances, John and Ann are not criminals. John is a lawyer who works on property law and human rights cases—helping asylum seekers and returning land taken in the past from black South Africans. Ann is a nurse who has spent most of her life in labor and delivery rooms in Africa and the Middle East. She moved from Ireland to Zambia when she was 22 because, she says, she “wanted to work in the sun”; there, she met John’s father, who was from South Africa. No, they are not criminals. They just happen to live in a very unfortunate location, a location cursed by dimwitted decisions made by people who lived half a world away, people who made designations on maps and in databases without thinking about the real-world places and people they represented.

John and Ann were victims of a technological phenomenon they could not understand and had no idea how to solve. They had come to accept these visits as a recurring annoyance, like the rain or a car alarm going off, but it escalated from an annoyance to a threat to John’s career when Benna Bok’s owners threatened to sue him for harassment. They did not believe him when he said it was a case of mistaken digital identity; they said they had filed a police report and threatened to report him to his professional association. So he went to work unraveling the curse on his home, and I helped him exorcise it.

The outline of this story might sound familiar to you if you’ve heard about this home in Atlanta, or read about this farm in Kansas, and it is, in fact, similar: John and Ann, too, are victims of bad digital mapping. There is a crucial difference though: This time it happened on a global scale, and the U.S. government played a key role.

“I had no idea what was happening,” Ann told me at a cafe in Durban, on South Africa’s east coast. “I thought it was a scam, that they were coming to the house to try to see what was inside so they could steal it.”

The house was robbed one time, in 2014. The intruder(s) took Ann’s phone, tablet, and jewelry she’d been given by new mothers in Oman, who tend to give gifts to the nurses who help deliver their babies. She didn’t attempt to track the devices down.

John thought there must be some kind of digital signal emanating from the house. He reached out to local internet service providers asking for help, called the company that made his modem, canceled the home’s landline, and sent an email to an international contact at Apple asking the company to look into the issue—all to no avail. He started keeping meticulous records of every visitor who stopped by, and wrote up memos about what was happening that he would print out and give to people who kept coming and accusing him of new crimes.

Then, in 2016, he spotted an article I’d written about a couple in Atlanta who had strangers showing up at their home repeatedly looking for lost smartphones. He sent me an email, but it was formal and vague, and framed the problem as if it were happening to a third party.

“To the extent that the couple referenced have found a solution, the writer would be pleased to hear from you,” he wrote.

I responded by sending him a story I’d written about a farm in Kansas that was located approximately in the center of the United States. The farm’s owner, Joyce Taylor, had been dealing with accusations of criminal activity for a decade and didn’t know why—until I called her and told her that her front yard was a hot spot in a database offered by a company called MaxMind.

Since 2002, Massachusetts-based MaxMind has been in the business of determining where in the world a digital device is based on its Internet Protocol (IP) address, which is the unique identifier a device needs in order to connect to the Internet. If you’re reading this story online, you’re doing it on a device using a IP address, and our servers have recorded that IP address. We have also probably mapped it in order to figure out whether you’re an American reader, or a European reader, or an African reader. You’re probably seeing ads surrounding this story that are targeted to you based on where we think you are, based on your IP address.

Companies like MaxMind have a few different ways to figure out where an IP address is located. They can do real-world research by sending cars out into the world, a la Google Street View, which look for open WiFi networks, connect to them, get their IP addresses, and then record their physical location. Or they can buy location information from apps on people’s smartphones, which correlate IP addresses to GPS coordinates. (You read that scary New York Times article about “apps that know where you were last night”? It’s companies like MaxMind that they’re telling.)

Absent these more precise methods, MaxMind can simply look at which company owns an IP address—that information is maintained by international non-profits who “keep the Internet running smoothly”—and then make an assumption about where the IP address is, whether it’s at the company’s office or generally located in the city where the company is based.

The thing about IP mapping that many people don’t realize (and I wish they would, since I wrote two huge stories about it in 2016) is that it is not an exact science. Sometimes an IP address can be mapped to a house—you can try to map your own IP address here—but in general, an IP address, at its most precise, just indicates what city and state a device is in. At its least precise, it simply reveals what country a device is connecting to the internet from.

But computer systems don’t deal well with abstract concepts like “city,” “state,” and “country,” so MaxMind offers up a specific latitude and longitude for every IP address in its databases (including its free, widely-used, open-source database). Along with the IP address and its coordinates is another entry called the “accuracy radius.”

The accuracy radius does what you might expect. It says how accurate the coordinates are; it indicates the 5-mile, or 100-mile, or 3,000-mile area included with “a point” on a map. Unfortunately, it is ignored by many geo-mapping sites such as IPlocation.net, which gets its data from IPInfo and EurekAPI, two more IP geolocation databases that use MaxMind as a source.

MaxMind provides location information to thousands of companies. Some use it to display local ads. Some use it to prevent fraud. Some use it to determine whether a customer is accessing the right version of their website or service.

MaxMind has never told me exactly what their secret sauce is for determining where in the world an IP address is located, but if it doesn’t know that much about an IP address, and knows only that it’s being used by a device somewhere in the United States, it previously gave the coordinates for the front yard of Joyce Taylor’s farm in Kansas; by the time I called her in 2016, 90 million IP addresses were mapped to her home in MaxMind’s database. Any time a device using one of those IP addresses did something terrible, those looking into it assumed the people who lived at the farm were responsible.

When I emailed the company’s founder Thomas Mather, back in 2016, asking why it had associated so many IP addresses with the Kansas farm, he’d been incredibly candid with me, explaining that the company had picked a default central digital location for the United States without realizing it would cause problems for the person who lived there. He asked me what the company should do to rectify the situation. “Do you have a sense of how far away we should locate these lat/lons from a residential address?” he emailed me back. “Do we also need to locate the lat/lon away from business/commercial addresses?”

I was a little stunned at the time to have the CEO of a company ask me for that kind of very basic advice about his own business. The company wound up changing the default location for the U.S. from Joyce Taylor’s farm to a lake nearby. Taylor and the residents of the farm later sued MaxMind; the case settled out of court.

MaxMind seemed to realize it had messed up badly. At the beginning of 2018, it said it was removing longitudes and latitudes from the free database it offered online, but according to a blog post last April, customers complained, so MaxMind decided to leave them. “Please remember to use the accuracy radius if displaying coordinates on a map,” MaxMind warned at the end of its post. It also preemptively moved other popular coordinates to places that wouldn’t result in harassment for private citizens.

“MaxMind has changed over a hundred frequently resolved coordinates,” Tanya Forsheit, a lawyer for the company, told me by email. “MaxMind chooses coordinates it believes won’t be misinterpreted to be associated with specific buildings or homes. These may include bodies of water, forests, parks, etc.”

Technologist Dhruv Mehrotra crawled MaxMind’s free database for me and plotted the locations that showed up most frequently. Unfortunately, John and Ann’s house must have just missed MaxMind’s cut-off for remediation. Theirs was the 104th most popular location in the database, with over a million IP addresses mapped to it.

I’m embarrassed to say that I didn’t figure this out in 2016, when John first reached out. I was getting quite a lot of emails at the time from people who hoped I could solve their tech mysteries, and John’s got lost in the flood. I shudder to think of the number of important stories that sit in the inboxes of journalists who are too harried to tell them.

But it wasn’t entirely my fault. When I visited John at his home in Pretoria this January, he told me he was hesitant to pursue the story with me because he worried about how it made him look to be the frequent target of criminal questioning. (He’s still worried about that, and asked not to be easily identifiable in this piece.)

“You want to be known for the good things you’ve done in life,” John told me, “not the bad things that have happened to you.”

He also thought it might just stop on its own after the Kansas farm story so clearly demonstrated how harmful faulty IP address mapping can be. The downside of this delay is that John and Ann continued to get visits over the last couple of years, as recently as last month when police showed up looking for a kidnapping victim. The upside is that John sought other help. He saw on Facebook that a classmate of his from Pretoria Boys High, the same English-speaking high school Elon Musk attended, was a computer science lecturer at the University of Pretoria. John sent him a message.

“I’m not the guru, this guy is,” the classmate responded, sending John contact information for Martin Olivier, a professor at the University. Within three days of John contacting him, Olivier discovered that MaxMind didn’t choose to put the target on John and Ann’s home on its own. It got help from the U.S. military.

Olivier, like me, received a very cautious email from John that didn’t name any particular person as the victim of the problem. “At first it didn’t make sense,” said Olivier over lunch at a cafe in Pretoria. “But as he told me more, it became pretty clear what had happened.”

Olivier is a stout fellow with salt and pepper hair—more salt than pepper—and a big bushy beard. When I met him, he was dressed from head to toe in blue jean and wearing blue leather shoes. I thought of him immediately as “denim Santa,” and then couldn’t shake that description from my brain. He speaks English with an Afrikaans accent, and has been teaching computer science in South Africa for three decades.

Olivier realized quickly that IP address geolocation was to blame, but he wanted to figure out why John and Ann’s house had been selected as a default location so he headed to Google.com. He mapped John’s home and got its latitude and longitude; let’s say it was-25.700062, 28.224437. He then tried a variety of searches involving those coordinates and wound up on a “Pretoria Prayer Times” website that told Muslims what time of day they needed to pray if they lived in Pretoria, as identified by the coordinates for John’s home.

It seemed like the coordinates represented Pretoria as a whole, so Olivier searched for “City GPS coordinates,” which landed him on MaxMind’s free database. He tried “City GPS database” instead, and after a number of false starts, as captured in the history of Google searches that he printed out for me, he wound up on a Google Answers page for “Database of world cities + GPS coordinates + population?” It was a thread about how to find such a database and one of the commenters mentioned a “HUGE file of city names that contains probably over a million names with lat/long data.” The person added, “It’s from the National Geospatial Intelligence Agency (who knew…?)”

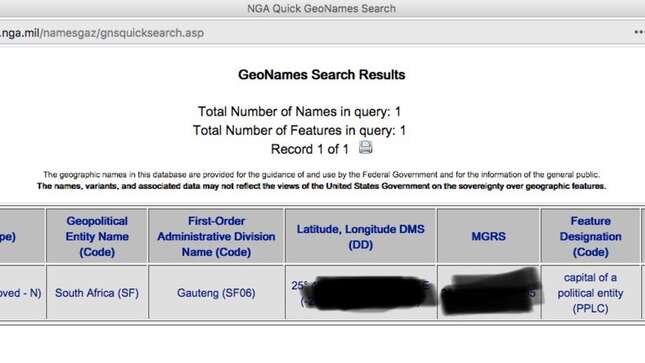

When Olivier visited the database and did a search for Pretoria, South Africa, he discovered that the designation for “the capital of a political entity” pointed straight at John’s house. When he looked up the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency’s website, he discovered it’s both a U.S. intelligence agency and part of the United States Department of Defense and “delivers world-class geospatial intelligence that provides a decisive advantage to policymakers, warfighters, intelligence professionals and first responders.”

A person familiar with the intelligence community told me the agency does analysis of satellite imagery for the military and intel community, to determine, for example, if a particular region is secretly building nuclear weapon sites. In 1999, when the agency was known as the National Imagery and Mapping Agency, it provided a map and satellite imagery analysis to the U.S. military that was used when NATO mistakenly bombed the Chinese embassy in Belgrade; agency analysts reportedly failed to recognize the building as an embassy. When the agency changed its name in 2003, it hyphenated “Geospatial-Intelligence,” so that, according to this person, it could have a vaunted three-letter acronym, like the FBI, CIA, and NSA. It goes by NGA.

Human beings conceive of the world as a giant map, as a series of places with lines drawn around them and labels inside the lines. The NGA is in charge of the official recording of the lines and labels for the entirety of the U.S. government (so that it works from a standard map of the rest of the world), but also for everyone who uses the NGA’s free online database. The only part of the world the NGA mostly ignores is the U.S. itself, because it is not supposed to be “spying” on Americans, and the U.S. Geological Survey takes care of local mapping.

“Yes, the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA) is one of the sources for data in the MaxMind databases,” a lawyer from MaxMind told me via email.

MaxMind determined that over a million IP addresses were operated by entities in Pretoria (such as South African ISP Telkom SA), and so it geolocated those IP addresses to the coordinates offered by the NGA for the city. And any time someone uses one of those IP addresses to do something bad—like cyberbullying the owners of a leather shop—it looks to someone who maps the address like the bad thing is being done by someone sitting in John and Ann’s backyard.

“Your simplest option may be to move ;-),” wrote Olivier to John in an email.

“Maybe my place will make a good parking lot,” John wrote back, convinced there was little he could do to combat misinformation being propagated by the U.S. military.

Olivier’s passion is digital forensics, and getting law enforcement, prosecutors and judges to better use technological evidence, so this was particularly frustrating for him. (He’s not alone.)

“The thing about IP location is we know it’s junk,” he told me. “It’s good for games and ads but not for anything formal.”

It’s not that IP addresses are useless for evidence gathering, but the proper approach is to go to the internet service provider that operates the IP address and get it to tell you who was using it at the time it did the bad thing. This usually requires a subpoena or court order, so regular people turn to IP mapping sites instead. And those sites sadly don’t tell people just how imprecise IP mapping is unless they read the fine print or click into the FAQ. (I asked one of the most popular sites, Iplocation.net, why they don’t have a more prominent warning about the imprecision of IP address mapping, but it didn’t respond to multiple inquiries.)

The free tools available to us online can give us an unwarranted sense that we know more, and to a higher degree of certainty, than we actually do.

“Welcome to the house of horrors,” John said to me, when an Uber driver dropped me off outside his house in Pretoria.

It was the first week of January, summer time in South Africa, and the sun burned brightly overhead. He was tall and dressed formally in a suit, but shook my hand warmly and invited me into his home. His house is on a major road and the sound of passing traffic was audible from his living room. He told me that he and his mother had been thinking about selling the home but felt like they probably wouldn’t be able to until the visitor problem was resolved, because they’d have to disclose it to any potential buyer.

John had gotten back in touch with me in October, frightened by threats he was getting from the leather goods shop Benna Bok and wanting to finally resolve the issue. This time I focused my full attention on it.

According to legal documents, a husband-wife team had launched the Benna Bok shop on Facebook a year earlier; they were immediately overwhelmed by the number of orders that came in for their simple leather shoes and handbags. They fell behind on production, and customers started getting angry about shipping delays. An anonymous person using the pseudonym “Frank Vermuelen” doxed the shop owners and their parents, posting their phone numbers and addresses online, calling them scammers, fraudsters, and thieves. The husband got a call from someone who threatened to “cut off his balls” if he didn’t get a refund for an unfulfilled order.

Benna Bok’s owners, feeling “terrorised,” somehow got Vermuelen’s IP address and mapped it to John’s home. Beyond their threats to sue John and report him to his professional association, Benna Bok announced in a series of Facebook posts that it would soon expose Vermuelen.

Benna Bok felt wrongfully accused of being fraudsters, but were perpetuating the cycle of wrongful accusation by going after John, who had never heard of the shop before it accused him of serial harassment. I reached out to Benna Bok and its lawyer repeatedly about the path that led them to John but never got a response. Customer dissatisfaction with the shop’s failure to deliver goods in a timely fashion is high enough that one of the owners was recently grilled on South Africa’s 60 Minutes. It seems unclear whether the shop’s owners are defrauding their customers or just really terrible business people, but either way, John is now thankful they came after him.

“It’s almost a blessing,” he told me. “I was hoping this would just go away on its own, but this forced me to do something about it. Before the problem was ephemeral. The police would come, look for something, and go away without finding it. But this time there was a case, something I could hold onto and fight.”

John took me on a walk around his block. All the houses had fences in front, some with barbed wire on top. Dogs barked at us as we passed many of the homes.

He took me to his backyard to show me the place that served as a homing beacon in an unknown number of databases. It was a big grassy space, with stones set in an approximately 20 by 20 foot square in the middle. There was a bird bath, an orange tree, a shed that served as a workspace, and a cat running around, keeping an eye on a black bird in the bath. It was deceptively serene and peaceful for all the trouble it had caused.

So why did the NGA choose this place to represent all of Pretoria?

“Our Political Geographers use medium-scale maps to place a feature’s coordinates as close to the center of a populated place as possible.” said NGA spokesperson Erica Fouche. “In this case, [John] lives near the capital. There was absolutely no intent to place the coordinates on his residence.”

“For additional context, our coordinates for politically sensitive features, such as Jerusalem, are precise and based on State Department specifications,” she added in a later email, as if to say the cartographers are not usually so casual about these things.

What is a place? What is its center? What best represents it? There are several different possible “centers” of Pretoria. There’s the zoological park. There’s Africa’s biggest mall. There are multiple government buildings that have served as political centers over South Africa’s long complicated history. There’s the Palace of Justice in Church Square, where Nelson Mandela was imprisoned. There are the Union Buildings, with the famous statue of Nelson Mandela, his arms upraised, which serves as the seat of the South African government. John and Ann’s backyard is in a suburb north of the city center, and it’s unclear how NGA’s cartographers decided it was a key location. It was a weighty, if apparently random, decision.

“I think it’s quite irresponsible,” said Ann. “You would imagine they would survey or do some kind of investigation before putting that beacon there.”

Fouche told me John and Ann could email the agency to “rectify the situation,” and gave me an email address that I passed along to John.

Once we knew what the problem was, it was relatively easy to fix. John’s lawyers emailed the NGA and, after about a month, they changed the coordinates to a location John’s lawyer recommended: Church Square, a historic center of Pretoria.

“Which basically means I’ve just put the crosshairs of the US military on oom Paul’s forehead, surely one of the greatest achievements of my life,” wrote John’s lawyer in an email, referring to a controversial statue in the square that commemorates Paul Kruger, an Afrikaner political leader from the late 1800s who fought the British and was part of a long line of South African leaders who oppressed the country’s black citizens. (“Oom” means “uncle.”)

I asked the NGA whether it would reassess other coordinates in its database to prevent something like this from happening again.

“NGA routinely modifies coordinates to maintain an accurate product and will continue to improve all our metadata as source availability allows,” a NGA spokesperson emailed back. “This is the first request from a private citizen to reassess coordinates that NGA’s GeoNames team has received in at least seven years.”

MaxMind chose to move the coordinates to a different location: a lake in an industrial part of the city. Two years after MaxMind first became aware of this problem with default locations, its lawyer says it’s still trying to fix it.

“MaxMind has taken significant steps to help reduce the likelihood of misuse of coordinates by third parties, and is currently working on finishing up a lengthy project to develop a tool to review all commonly used coordinates and make adjustments as needed,” said Tanya Forsheit, the company’s lawyer, by email. When I asked for more details about the “tool,” it turned out to be a visualization of “where in the world a given latitude and longitude pair appears on a map [with the ability] to make and save adjustments, as necessary, after two people conduct manual review.”

Forsheit could not provide a timeline of when MaxMind would be able to more thoroughly review the coordinates in its database but said MaxMind “anticipates that it will begin incorporating adjustments by January.” She also said MaxMind is “fine-tuning its messaging about the meaning of latitude and longitude coordinates in its databases and services.” Companies who use the database to display a location are supposed to tell their users that the point on a map is actually a large blob on a map.

And that’s the problem, really. John and Ann’s problems weren’t necessarily caused by one bad actor, but by the interaction of a bunch of careless decisions that cascaded through a series of databases. The NGA provides a free database with no regulations on its use. MaxMind takes some coordinates from that database and slaps IP addresses on them. Then IP mapping sites, as well as phone carriers offering “find my phone” services, display those coordinates on maps as distinct and exact locations, ignoring the “accuracy radius” that is supposed to accompany them.

The victims of theft, police officers, private investigators, the Hawks (South Africa’s FBI), and even foreign government investigators showed up mistakenly at John and Ann’s door, and none of them ever tried to figure out why.

“We assume the correctness of data, and often these people who are supposed to be competent make mistakes and those mistakes then are very detrimental to people’s daily lives,” said Olivier. “We need to get to a point where responsibility can be assigned to individuals who use data to ensure that they use the data correctly.”

A strange side effect of the changes made by NGA and MaxMind was that a search for the coordinates for John and Ann’s house on Google Maps showed a location pin in their back yard but Google Street View photos of Tshwane City Hall. Google said this was the result of “a backend bug” when I asked about it.

Olivier said there’s likely no one in the world who really understands how all these databases interact.

“There’s an interesting interrelationship between the various data sets. What seems like a local change might have a global effect,” said Olivier. “Until we understand those changes, we should be very careful to rely on these huge datasets.”

As long as the changes that the NGA and MaxMind made get distributed to any other databases that were relying on them, the nightmare is probably over for John and Ann. But there are very likely other people in the world living in homes with the same problem, who don’t know why it’s happening to them, who don’t know who is causing it, and who have no idea how to solve it. Hopefully they find this story.

Contact the Special Projects Desk

This post was produced by the Special Projects Desk of Gizmodo Media. Reach our team by phone, text, Signal, or WhatsApp at (917) 999-6143, email us at tips@gizmodomedia.com, or contact us securely using SecureDrop.