The secrets of a diary written on castle floorboards

- Published

A hidden diary written by a carpenter on the floorboards of a French Alpine chateau provides a rare insight into the private lives of villagers in the late 19th Century, writes Hugh Schofield.

When the new owners of the chateau of Picomtal decided to renovate the parquet in some of their upstairs rooms, they made a remarkable discovery.

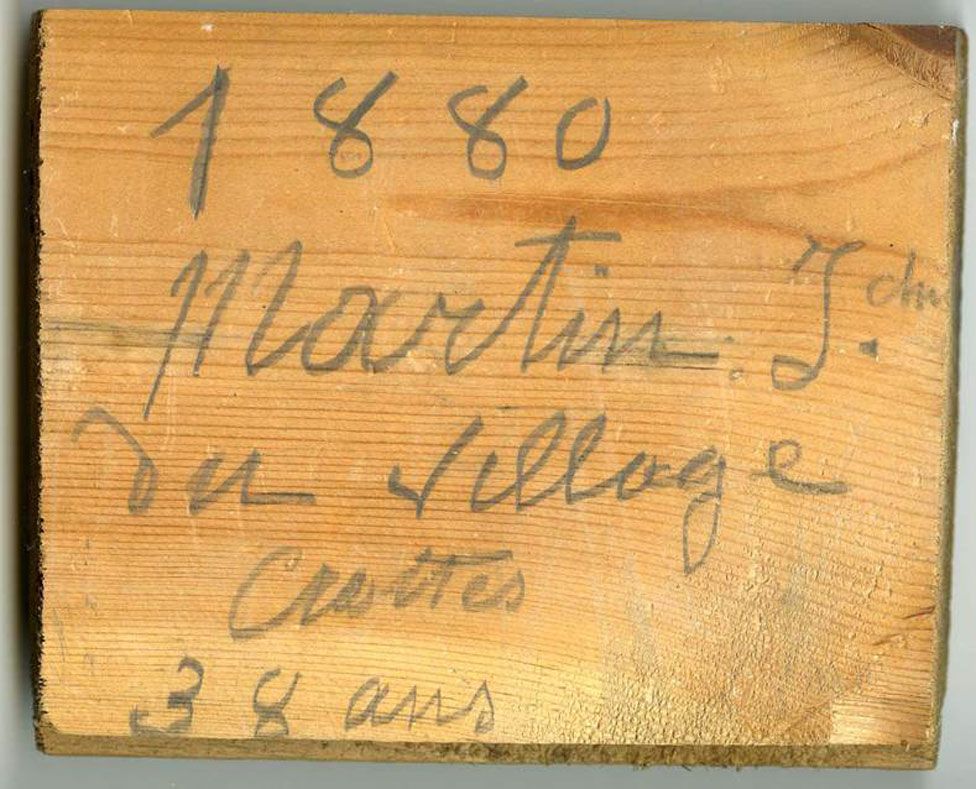

On the underside of the floorboards - invisible until the boards were taken up to be replaced - were long messages written out in pencil. The messages were dated over several months between 1880 and 1881, and they were signed by a certain Joachim Martin.

Joachim Martin, it quickly became clear, was the carpenter who installed the parquet for the chateau's then owner - and what he left behind was a kind of secret diary intended to be read only long after he was dead and buried.

In 72 entries - some longer than others, some purely factual, others pulsating with personal feeling - Joachim sets out what is in his head as he goes about his daily work.

"These are the words of an ordinary working man, a man of the people. And he is saying things that are very personal, because he knows they will not ever be read except a long time in the future," says historian Jacques-Olivier Boudon of Sorbonne university.

Personal it certainly is. Joachim's diary touches on matters of sex, crime and religion - and sometimes a combination of all three! - allowing us an extraordinary behind-the-scenes glimpse at the goings-on in the small rural community of Les Crottes, just outside the chateau walls.

The most shocking episode deals with an infanticide - a story that clearly still haunts Joachim 12 years after it occurred.

"In 1868 I was passing at midnight before the doorway of a stable. I heard groans. It was the mistress of one of my old friends and she was giving birth."

Over time the woman gave birth to six children, Joachim informs us, four of which are buried in the stable. He makes clear that it was not their mother who killed them, but her lover - his old friend Benjamin - whom Joachim accuses now of trying to seduce his own wife.

"This (criminal) is now trying to screw up my marriage. All I have to do is say one word and point my finger at the stables, and they'd all be in prison. But I won't. He's my old childhood friend. And his mother is my father's mistress."

There - according to Boudon, who has published a book called Le Plancher de Joachim (Joachim's Floorboard) - we have an insight into the reality of village relationships which no conventional archival text could come close to.

Joachim feels horror at the multiple infanticide, but he will not denounce it because of the intimate connections that link his and Benjamin's families, who are neighbours. The killing of babies was certainly a criminal offence but at a time before contraception was available it was perhaps not that uncommon.

Joachim's diary implies that in places like the village of Les Crottes infanticide was taboo. People knew it went on, but no-one spoke out.

Quite possibly the pressure of the secret was one factor that prompted Joachim to unburden himself on his planks. Another appears to have been his anger at the local priest.

The 1880s were a time of rapid change. France's Third Republic was bedding in, having seen off a final challenge from the monarchists, and across the country reforms were being introduced that limited the powers of the church.

Joachim approved of these reforms - principally, it seems, because of his personal animosity towards the Abbé Lagier; he thought he was an obsessive womaniser, who abused the confessional for sexual kicks.

On one of his planks, Joachim writes: "First I find it very wrong the way he sticks his nose into our family business, asking about how one makes love to one's wife." (Actually, he uses a more vulgar term.)

"He wants to know how many times a month," he writes, adding more detail of a vulgar nature concerning different sexual positions. "The pig should be hanged."

In the same entry he describes the village priest as "a bit of a lad, there he is bowing to the women while the poor cuckold husbands have to keep quiet".

According to Boudon, the Abbé Lagier may not have been acting totally beyond his brief in asking women in the confessional about their sex lives. In fact many priests at the time did this, on the religiously-sanctioned grounds that couples had to be discouraged from engaging in practices that would not result in the birth of a child.

What the episode shows is how such priestly prying created resentment, and thus contributed to the growing anti-church feeling.

Interestingly, Boudon has unearthed other evidence that corroborates the tensions in Les Crottes between priest and congregation. In 1884 a petition was sent to the local parliamentary deputy asking for the Abbé Lagier to be replaced. Several letters were sent to back up the petition, and one of them (which has been preserved) was written by Joachim.

The arguments used by the petitioners were, first, that the Abbé abused the confessional (and by implication that he was morally dissolute). And second, that he was a miserably incompetent doctor...

Here we have another fascinating insight into village life. It turns out that many parish priests at the time doubled as guérisseurs - or healers - much to the infuriation of the medical profession. But doctors were thin on the ground, and priests were used to accompanying the sick.

Joachim and his fellow parishioners don't seem to have had a problem with this in principle. Their objection is simply that, as a doctor, the Abbé was no good.

It is also an intriguing fact that the petitioners asked not for a Catholic priest as a replacement for the Abbé, but for a Protestant - this despite the fact that there were very few Protestants in Les Crottes (Joachim's mother was in fact one of them).

What this shows - says Boudon - is how in people's heads the rigid distinctions between Catholicism and Protestantism were not nearly as marked as is generally thought. In the circumstances, the idea of a married (and presumably less lecherous) pastor was quite appealing.

Of Joachim Martin himself we know only a little. He was born in 1842 and he died in 1897. As a young man he earned money as a fiddler at village fetes. He had four children. No photograph of him is known to exist.

But according to Boudon, the carpenter was clearly a man of intelligence and sensibility.

In his hidden diary of wood, he addresses directly the unknown reader who he hopes will one day come across his traces: "Happy Mortal. When you read this, I shall be no more." And elsewhere: "My story is short and sincere and frank, because none but you shall see my writing."