The most important part of any review I write for Ars is the experiential component—that’s what I seek out whenever I’m reading a review somewhere, and that’s the part I try to focus the most effort on. "Speeds and feeds" are nice, of course—you can’t really have a review, especially a product review, without stats and quantified performance and all the rest of that stuff—but the ultimate question a review has to answer is, "What is that thing like?"

With an application or a product, photographs and screenshots are a core component of conveying the experience of using that application or product—and screenshots are a poor tool for telling you what it’s like to use an Oculus Rift, especially when coupled with a well-executed transformative VR gaming experience like Elite: Dangerous is turning out to be.

I’ve been playing Elite: Dangerous exclusively with the Rift DK2 for several weeks now, stealing an hour or two every few days (much to my eyes’ detriment, apparently), and I’ve been struggling with how to convey the experience. I mean, I could drop the standard boatload of verbiage about how awesome it is—it is awesome!—but what does that really tell you?

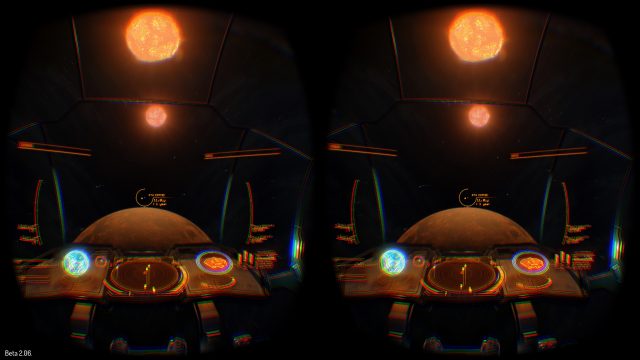

I could post screenshots. Here’s what Elite: Dangerous looks like with the Rift DK2:

But what does that tell you? That Elite: Dangerous features muddy graphics and suffers from chromatic aberration? That the game looks kind of brown, kind of orange, and kind of meh?

Let me tell you what was happening when I took that screenshot. I had undocked from Ray Colony, the main settlement in LFT 1446 (there’s a reddit thread featuring a non-Rift screenshot here), and I was headed back to Isherwood Ring station to drop off a load of marine supplies. I locked onto Eta Cephi and was swinging my ship’s nose to point in the right direction for the jump and bam, there it was—a perfect stellar conjunction, like something right out of Kubrick, lacking only a monolith to make the image complete. The system’s binary suns hung in space above me, big as God, while my referent star sat between them and the planet dominating the bottom quarter of my view.

It was, literally, breathtaking.

I stared at it for probably a full minute, just marveling in the stillness and enormity of space and the planets. In 3D, through the Rift, those suns had weight as they hung there in the black; the planet below has a looming solidity, and I felt a vertiginous sense of height as I looked down at it. I realized I had to at least try to capture what I was looking at and feeling, so I snapped a few screenshots, wondering how they’d turn out—wondering if there was any way the distorted image would be able to capture the awesome, awe-inspiring vista that lay spread out in front of me.

Of course, it didn’t. The image looks how all Oculus Rift screenshots look. It looks like garbled crap.

More real, and more isolated

Even after weeks, Elite: Dangerous with the Rift DK2 makes me stop and say "holy crap" at least once per session. The game supports the latest Oculus SDK revision, which means that it can tell not just where your head is pointed, but it also fully understands where your head is. The positional tracking is executed with fluidity and grace. When using the Rift with first-person games (like Alien: Isolation, for example, which has experimental Rift support that can be enabled by flipping a single config file option), you can use this positional tracking to lean around corners or duck simply by moving your head, but that mobility only gets you so far when you have to return to your mouse and keyboard to actually move your avatar.

Elite: Dangerous neatly sidesteps this issue by simply having your player character remain seated. This solves the potential problem of reconciling the Rift’s positional movement with your game’s character (like whether or not your in-game avatar should shuffle left or right if you move your head laterally). You’re strapped to your cockpit chair, and so there’s no need to worry about what your avatar is doing or how to square "real" movement (i.e., where your head is) with WASD input and mouselook.

This also neatly blends with what the real you is probably doing when you play Elite—you’re almost certainly sitting in a chair. If you look down in the game, your view pans down to see a flightsuited body also seated in a chair, grasping the ship’s stick and throttle. If you also happen to have your left and right arms extended in front of you holding a HOTAS-type setup, your body’s proprioception matches nicely with what your eyes are seeing, and you experience an odd momentary blurring of self—proprioception is a weird thing, and it’s easy to allow yourself, just for a moment, to think that the body you’re seeing is yours.

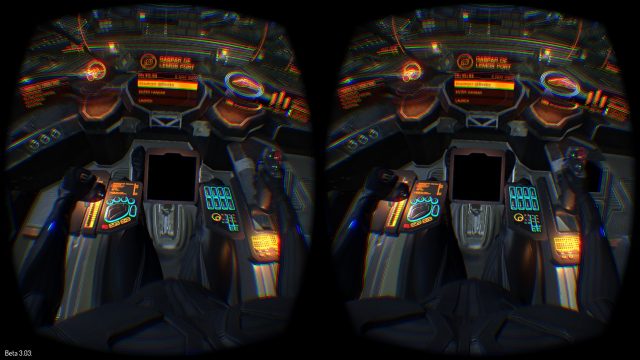

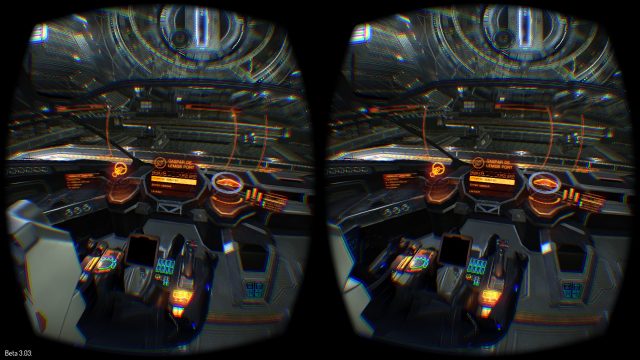

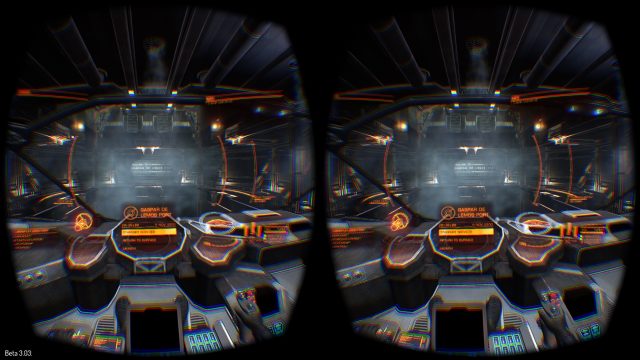

It’s one thing to be able to look around the ship’s cockpit. That’s easy and probably the first thing anyone does. But once you realize you can move your head, a whole new way of interacting with your spaceship reveals itself. Can’t quite read the text on a control panel? Lean forward. Need to check above and behind you while you’re undocking to see if there’s a ship about to crash into you? Lean forward and crane your neck or look back over your shoulder like you’re checking the blind spot in a car. The increase in immersion is stunning, because automatic actions yield expected results—you really can see a bit more out of your Cobra’s side window if you crane your neck in that direction a bit, just like in a car.

-

Looking forward.

-

Leaned forward, looking left.

-

Looking back above left shoulder.

-

Leaning far forward, looking over left shoulder.

Of course, the most incredible thing you can do in Elite: Dangerous right now with the Rift is non-obvious—it took me a few days before I even realized I could do it.

You can stand up and walk around your cockpit.

Freedom

I need to clarify here—the designers haven’t yet added a "first person" module where you can walk around in your ship (the Star Citizen folks just took the wraps off of exactly that feature for their game last week at PAX Australia, in fact). Such a module is eventually coming, but this isn’t that. All you’re doing when you stand up is moving your viewpoint around in the cockpit—your headless avatar remains disturbingly seated in the pilot’s chair.

But oh, what it feels like.

The Rift DK2’s orientation and positional tracking, for those who haven’t experienced it, is remarkable. The standout feature is that it tracks even the subtle muscle twitches your head and neck make, and the device’s latency is low enough that those kinds of subtle movements are incorporated seamlessly into your view—in other words, if you stare hard at the pixels making up the image in front of your eyes, you can see that they’re moving a lot more than you might think in response to your own body’s subtle movements. The orientation and positional tracking remain note-perfect when you physically stand up and move.

I think the first time I "got up" from my cockpit chair was when I needed to get a kleenex or something while playing. I leaned away from the desk and flailed my arm in the direction I knew the thing to be, but couldn’t reach, and so without pulling the Rift off my face, I scooched over to grab the kleenex box. My view slid in the same direction, far off of my avatar’s neck; surprised, I looked back and beheld my own body, calmly still sitting in the chair, flying the ship.

It was an epiphany, and I stood up and walked around the cockpit of my starship for the first time. The illusion of actually being there is completely convincing—well, except for the fact that your in-game body stays seated in the chair. You’re limited only by the length of the DK2’s HDMI and power cables—they’re 10 feet long (a bit over 3 meters), and the DK2’s standalone infrared camera is capable of tracking the Rift as far out as I can stretch the cables. You'll occasionally bump into the edge of the camera's field of view, but the production Rift is expected to have an even wider field of view.

Even viewed through the screen door effect of the DK2, the cockpit environment is stunning. It’s not so much that the graphics are all that great—the relatively low resolution of the DK2’s screen makes everything fuzzy, and there’s really no way around that—but rather that the 3D effect is so smoothly rendered and tracks so perfectly with your head and position. You can walk around the ship’s cabin, kneel, stand, lean in to look more closely at little details—you can even, if the ship is a small one like the Sidewinder, poke your head out through the roof and see the stars unroll above you like a limitless vast blanket of night.

And the damnedest part is that no amount of screenshots or video can describe it to you all.

No one can be told what the Matrix is

The paradox of the Rift’s virtual reality experience is that it is ultimately a closed and private one—much in the same way as it’s impossible to bring another person fully inside your own head to show them exactly what you see, it’s impossible to really share what using a Rift is like. You really do, as Morpheus says, have to see it for yourself.

I’ve played as many Rift demos as I can get my hands on, and I’ve forced as many games as I can to work in VR mode, even battling Surgeon Simulator for an hour or so to try to make it function properly with the Rift, but the simple act of walking back and forth in my spaceship’s cockpit in Elite hands-down beats anything else I’ve seen so far with the Rift.

Maybe it’s because you physically have to walk, and the area in which you can walk is relatively tiny—most ships have a small cockpit (though not all—I haven’t yet acquired the credits to wander around in the enormous Anaconda’s cockpit), and that space matches up well with the area that can be navigated with the DK2’s cable tether. Maybe it’s because by pairing physical real-world movement with dead-on positional and rotational tracking, I didn’t feel even a tiny twinge of nausea or vertigo—what your viewpoint is doing on-screen exactly matches what you’re doing in real life.

Maybe because for as long as I can remember, I’ve wanted to fly my own spaceship. And now, it really and truly feels like I am. The cockpit and holographic instruments are great, but it’s that sense of presence that makes it so powerful. Standing and looking out the side window of my ship while I cruise is just—addictive.

When games are designed with VR in mind, and when those games are coupled with good hardware, the resulting experience can finally deliver on a lot of the promises we were all made in the 1990s about how head-mounted displays would look and function. I’m already glad I spent the money to buy the DK2.

I just wish there was a way to bring you all along for the ride, because it’s really that good.

reader comments

119