The Justice and Security Act introduces so-called “secret courts” (Closed Material Procedures) into ordinary civil cases in Britain for the first time. Despite vehement opposition, it gained Royal Assent on 25th April 2013. It has not yet come into force. The rules of court provided for under the Act have not yet been passed. So, as yet, the procedures for secret courts are not being used. It is only a matter of time, however, before secret courts are in use in civil cases across the United Kingdom.

Closed Material Procedures (or “CMPs”) mean that one party is not able to take part in either part or the whole of a trial. This party will almost always be a civilian who is bringing a claim against a government agency. It could be a civilian who is the defendant in a case. The government and its lawyers are present during the CMP. The civilian and their lawyer

- cannot be present,

- cannot see the evidence the government is relying upon (and which is said to be national security sensitive information),

- cannot know the government’s case on this evidence,

- cannot challenge this evidence or the government’s case and

- cannot know the reasons for the judge’s decision on that evidence and therefore (at least a part of) their case.

The civilian will be told whether they have won or lost, but not the full reasons why.

The Act applies to “relevant civil proceedings”, which means any civil proceedings in the High Court, Court of Appeal, Court of Session or the Supreme Court[1]. This means that any civil case in any of these courts may be affected by this legislation if sensitive information is required to be disclosed in the course of the case. Sensitive material means material the disclosure of which would be damaging to national security.[2] The cases affected include the writ of habeas corpus and claims for damages for torture, kidnap, assault and negligence.

The final stages of the debate about the Justice and Security Act became a confusing melee of allegation and counter-allegation about the effect of the legislation. Now that the Act is passed, how will it impact on live cases?

Below are four scenarios closely based on real-world case studies. They set out the cases so far, then imagine how they might proceed now that secret courts are a reality.

Scenario 1: Hassan

Based on the case of Abdul-Hakim Belhaj. Read more here.

Hassan had been a prominent spokesperson against Colonel Gadaffi in Libya. He had been forced to flee Libya in the 1990s and had originally lived in the UK. He had then lived in the Far East with his wife. He and Eman had been living in Kuala Lumpur for some time.

One day in 2004 they were both arrested when trying to travel back to the UK. Hassan was held separately from Eman and was not given any information about how she was or where she was. He was desperately worried about her as she was pregnant.

Hassan was very frightened for himself and for his family. He was right to be.

Hassan was kept for days by the CIA. He was mistreated and beaten.[3]

Hassan was transported to Libya and handed over to the Gadaffi regime’s security services. Hassan had spent time in custody in Libya before and knew what to expect. He was held for nearly two years at the prison. While he was there he was tortured.

There was a trial in Libya but Hassan was not allowed to have much to do with it. At the end of the trial Hassan was sentenced to death. He hadn’t really expected any other outcome – everyone knew how trials worked at that time in Gadaffi’s Libyan dictatorship.

While Hassan was back in prison Gadaffi was overthrown. Hassan then became an important figure within the new government. In September 2011 during the chaos as the Gadaffi regime collapsed a British journalist found papers in a building which had been occupied by the Libyan security services. These papers included an email from the head of the British Security Intelligence Service MI6 to Gadaffi’s head of the spy service. The email mentioned Hassan. It said:

"I congratulate you on the safe arrival of Hassan. This was the least we could do for you and for Libya to demonstrate the remarkable relationship we have built over the years. I am so glad. The intelligence on Hassan was British. I know I did not pay for the air cargo. But I feel I have the right to deal with you direct on this."[4]

Hassan had already started his case against the British government, the head of MI6 and the Foreign Secretary when the email was found.

The discovery made Hassan even more certain that he and his wife were doing the right thing. The truth had to be uncovered to make sure such things never happened again. What had happened to Hassan and Eman was against the law. Hassan knew that without the truth being exposed, the people responsible would never be made accountable for what they had done to him, Eman, and probably many other people.

…

On 25 April 2013, the Justice and Security Act was passed. The following text, in italics, is a fictional account of what may occur in Hassan’s case from this point. It demonstrates the dangerous possibilities opened up by the new legislation.

After the passing of the Act, Hassan’s case was made the subject of the Closed Material Procedure. Hassan’s lawyers explained that the legal test for whether a CMP was allowed was not very strict. [4a] Hassan’s lawyers said that the government were allowed to use material which was irrelevant to the issues in the case as the basis for its application for a secret hearing[5]. So the government could have been telling the judge about the intelligence information they had from a source in Kuala Lumpur that gave details of how Hassan was suspected of being “dodgy”.

Hassan was told by his lawyers that the judge had ordered the British government to give Hassan a summary of the material it wanted to rely on in secret. The British government had decided not to give Hassan or his lawyers the summary of material[6]. There was nothing Hassan could do about this.

A security cleared lawyer was appointed to speak to the judge about Hassan but she had no responsibility to Hassan’s interests. Once the Special Advocate had seen the evidence which the Defendants were relying on, she couldn’t speak to Hassan about anything to do with his case.

Hassan’s lawyers explained to him that it was not possible for him to know what material was being relied on by the government in its application for the CMP to be used in his case, or the evidence introduced under the CMP.[6a] Hassan’s lawyers had explained to him that this was the situation; Hassan personally found it difficult to see how a lawyer could possibly do anything for him when Hassan himself didn’t know anything about what was being said about his case in secret, and couldn’t tell the Special Advocate anything at all.

Later on Hassan was told he had lost his case. He was bitterly disappointed, but not surprised.

He asked himself: Where would he find a fair trial, if not in the UK?

Scenario 2: Eman

Based on the case of Fatima Bouchar, wife of Abdul-Hakim Belhaj. Read more here.

Eman is the wife of a Libyan former dissident, Hassan.

Until 2004 she and her husband had been living in exile. They were accustomed to a life of upheaval for themselves and their family. Little they had experienced before could have prepared Eman or her husband for the day they were kidnapped.

When she was five months pregnant Eman and her husband were kidnapped and held by CIA agents in Kuala Lumpur. The CIA had been told their whereabouts by MI6 agents in the UK (Eman and her husband had spent some time in London before living in the Far East).

Eman was not suspected of any criminal or terrorist activity. She was visibly pregnant. The CIA handcuffed her to a wall for five days. She was given water, but not food during the entire time she was handcuffed to the wall. She was not able to care for herself or for the health of her unborn child.[7]

When she and her family were moved by air, she was shackled to a trolley for the duration of the flight[8]. Her body and face were bound, and her right eye was taped open for the entire journey. Eman was not accused of any crime. She was not accused of anything other being married to a man considered undesirable to certain governments at the time.

Eman and her husband were returned to Gadaffi’s Libya, where her husband was put on trial. She and her daughter were released after two months in gaol.

Some years later, the information became available which strongly suggested that British agents had been involved in helping with Eman’s kidnap by letting the CIA know where she was. Eman and her husband issued claims for damages for kidnap and assault under the ordinary common law of England and Wales. The Defendants were the British government, the head of the Secret Intelligence Service and the then Foreign Secretary.

During 2012 the Defendants to Eman’s case tried to delay the litigation.

Eman and her husband offered to settle their claims on the basis of £1 in damages from each Defendant plus a full admission of liability and an apology. Despite this, the delays continued.

Eman and her husband did not know what Defence was being put forward by the Defendants. Were they going to argue that it was permissible to facilitate kidnap? Were they going to make allegations about Eman herself being involved in “dodgy” activity? Would they argue that being chained to a wall for three days was not cruel and unusual treatment? She had no idea, and her lawyers couldn’t tell her.

…

Once the Justice and Security Act passed in 2013 the Defendants became more aggressive in their conduct of the litigation. They indicated that they would seek to use the Closed Material Procedures provided for by sections 6-14 of the Act.

Eman was told one day that her lawyers had heard from the High Court, responsible for Eman’s claim. A specially trained and security cleared judge had been appointed to hear an application for CMPs to be used in Eman’s case. Eman’s lawyers were told about this before the application was made[9]. The application was granted. This meant the majority of her case would be held in closed court. Eman and her lawyers would not be allowed to be present in court.

After that application was granted, Eman found her case more difficult to cope with. She was very angry about how she and her family had been treated.

Fair trials did not happen in Libya under Gadaffi. But Eman had always understood that Britain was a country where fair trials happened.

Eman found it hard to remain calm as her case continued without her.

Eman was told by her lawyers that no one would be representing her – the Attorney General had decided it wasn’t necessary[11]. Eman was told that this decision was likely to be unlawful, following a case from the European Court of Human Rights, but the only way to challenge the Attorney General’s decision was by judicial review. There was no public funding available for the judicial review part of Eman’s case and she did not have the money to pay for this privately.

Eman asked her lawyers: How would she be able to tell the judge if the government were saying things about her and her family which were untrue, when she didn’t know what was being said? They couldn’t answer.

The case continued and eventually Eman was told she and her family had lost. She was able to see what her lawyer told her was an “open judgment” which said very briefly that her claim had been dismissed. Her lawyer told her there was also a closed judgment, which meant it had been given in secret. This judgment explained the evidence relied upon by the British government and the other Defendants, and explained fully why her case was dismissed. The Special Advocate had seen this judgment, but couldn’t tell Eman or her lawyers what it said. Eman and her husband and their lawyers would not be allowed to see it, ever.[12]

This seemed very unfair to Eman. How could she know if she should appeal? How could she ever find out what had led to her kidnap?

Eman had brought a case against the British government and the other Defendants because she wanted to know why her health and freedom had been attacked by people working for and with Britain. For her the damages claim she had brought (seeking money as compensation) was not important. She wanted to know who was responsible for making the decisions which endangered her and her unborn child. She wanted to know why they had decided to facilitate her family’s kidnap and her husband’s torture. She wanted to know why her unborn child’s life had been put at risk.

She had failed.

Scenario 3: Salwa

Based on the case of Khadija Al-Saadi, the daughter of Libyan dissident Sami Al-Saadi. Read more here

Salwa was twelve years old when she was kidnapped by the CIA along with her mother and father. She was not accused of anything other than being the daughter of a man considered undesirable by some governments at the time.

When the Justice and Security Bill was being debated in parliament she wrote to the Minister responsible:

“…I told him that having a secret court judge my kidnap was the kind of thing Gaddafi would have done. All he would say was that secret trials do ‘justice’ because more evidence would go to the court. But how is it fair for spies to whisper in the judge’s ear?..[13]”

Despite Salwa’s plea, the Justice and Security Act was passed…

Salwa lost her case too. She was not allowed to know why. She had learned from her mother and father about principles of fairness and freedom. They had told her that many of the principles for which they had fought and sacrificed for many years were things they had read about from history, and were things for which the United Kingdom had been renowned. Salwa didn’t understand how the UK government could tell the world about freedom and fairness and human rights, when its own courts refused her case in secret.

Scenario 4: Connor

This case study is based on the case of Martin McGartland, who acted as an informant for MI5 in Northern Ireland for many years. More information about Mr McGartland’s case can be found here.

Connor worked for MI5 as a mole in Northern Ireland within the IRA in the 1980s. He was credited with saving the lives of dozens of British soldiers through the intelligence he provided. After he stopped working for MI5 he lived in a safe-house. He was there attacked and shot by the IRA. MI5 has refused to pay for his continuing treatment for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. So Connor has brought a claim for damages to cover the cost of his treatment.

MI5 have applied to use a CMP to defend the claim[14]. If the application is successful, neither Connor nor his lawyers will be present in court to find out why MI5 decided to stop paying for his medical treatment.

…

These four are scenarios which are now possible following the passing of the Act, involving people who have been struggling for justice for years. These case studies may be enough of a warning. But in assessing the potential damage to be wrought to our justice system by the Act, we must look beyond the cases we know about which are currently in court.

Below are four imaginary scenarios that nevertheless demonstrate how Closed Material Procedures may operate in future.

Scenario 5: James

James lives in London and is a British citizen. In February 2015 he was detained under the new powers given by the Terrorism (Prevention) Act 2014. He issued a writ of habeas corpus to try and find out why he has been imprisoned and to challenge the reasons for his detention.

The government successfully applied for the case to be heard under a CMP. James loses his case. He is never told what the allegations are against him, which led to his detention. He remains in custody [15].

Scenario 6: Helen

Helen was a Private in the British Army and served in Helmand province. She was severely injured when a piece of equipment (provided by the Army) exploded at her base. She brought a claim against the Ministry of Defence seeking damages for her injuries. Her claim is based in negligence – the failure of the MoD to ensure proper maintenance of the equipment which blew up.

The MoD defend the claim and seek to use a CMP to determine the issues, claiming, successfully, that the information about maintenance procedures for the equipment involved is sensitive information as defined in the Justice and Security Act [16]. Helen loses her case, and does not know why.

Scenario 7: Maggie and Dennis

Maggie and Dennis are political protestors. They regularly campaign against nuclear power stations. This includes demonstrating outside. On occasion they have managed to get over the wire into the power stations to unfurl large banners.

The government obtain civil injunctions against Dennis and Maggie based on secret evidence which they do not see. Later, Dennis and Maggie are accused of having breached the injunctions. Secret evidence is used against them and they are found guilty of contempt of court without knowing how they are alleged to have breached the injunctions. They are each imprisoned for 24 months for contempt of court.[17]

Scenario 8: Jane

Jane is a journalist for a national newspaper. She is writing a story about corruption in arms dealing with Saudi Arabia involving government Ministers and UK officials. They sue Jane for libel. She defends the case relying on the defences of truth and fair comment and qualified privilege. The Claimants rely on secret evidence of falsity and malice in a CMP (because sensitive material is said to be in issue – namely security relationships with the Saudi government). A gagging injunction is granted against Jane on the basis of evidence which she has never seen and never will see, and cannot challenge[18].

Public review of the Act

The Justice and Security Act is not subject to a sunset clause. The Act provides for one review of its working after five years. [18a]. Unless it is repealed it will remain in force forever.

The Act requires that an annual report into the use of CMPs is placed before Parliament. This must be done “as soon as reasonably practicable” at the end of the twelve month period to which it refers[19]. This report must set out the number of applications made for CMPs in that twelve month period, the number of declarations made during the twelve months, that CMPs are applicable, the number of revocations during the twelve month period, the number of final judgments which are closed judgments and the number which are not closed judgments[20].

The Secretary of State may include other information as s/he sees fit, but is not required to do so[21].

The Act therefore does not require much information to be made public. It does not let the public know in what sort of cases applications for CMPs are made. It does not tell us (of course) the grounds for these applications or the reasons why the applications were or were not successful. We may, through open judgments after any CMP is revoked, find out why this occurred, but this is by no means certain.

What is already clear, based on press reports since the Act received Royal Assent on 25th April, is that cases are being lined up by the government lawyers to use CMPs. [22]

What can we do about it?

The first step is vigilance. The legal profession, journalists and campaigners need to develop a system whereby any application for a CMP is registered with as much information about the case as is lawfully available – for example case number, details of the parties, particulars of claim and other pleadings, case summary (if available), issues raised by the claim and defence. The media needs to be encouraged or persuaded to report these cases frequently and regularly, and as soon as they are aware of a new case as the Independent and Guardian have done recently[23].

Secondly, those concerned about the use and spread of CMPs need to liaise and work together. Human rights/civil liberties NGOs, academics, journalists, lawyers, politicians and the general public can all assist one another in this work. No popular movement against the spread of secret courts, and a secret body of law, will be possible without collaboration and cooperation.

Thirdly and related, any official report or review of the operation of CMPs needs to be properly examined and scrutinised, and questions asked.

In April I wrote for openDemocracy about the role played in the passage of this legislation by David Anderson, the Government’s Independent Reviewer of Terrorism Legislation. Mr Anderson took the trouble to respond to my criticisms of his actions, and openDemocracy published the response. He appeared to agree with at least some of the points I made, and I am pleased to note that the wording on his website changed after his response was published. It may be that Mr Anderson’s role will be important in future scrutiny of this Act. It may not help that, as I understand it, Mr Anderson has no professional experience of Closed Material Procedures. It certainly does not help that the role of Independent Reviewer is a part-time position. Mr Anderson’s proposals for additional safeguards in the Justice and Security Act were, in the end, rejected by the Commons. [24]

Whoever has the role of Independent Reviewer, they need to be clear with the public about whether the application for a CMP and the use of CMPs in each case is proportionate and appropriate, in their view, and to ensure as much as possible that the Security Services are not using CMPs to try and cover up wrong-doing or error. To this end, the Independent Reviewer must be provided with unfettered access to the cases which involve applications (whether successful or not) for CMPs. He or she may be the only official safeguard against significant abuses of power.

The role of those who have a function in examining this legislation – whether the Joint Committee on Human Rights, or Select Committees, or individuals, will be crucial. Those of us who are not in such a privileged position can and must hold them to account.

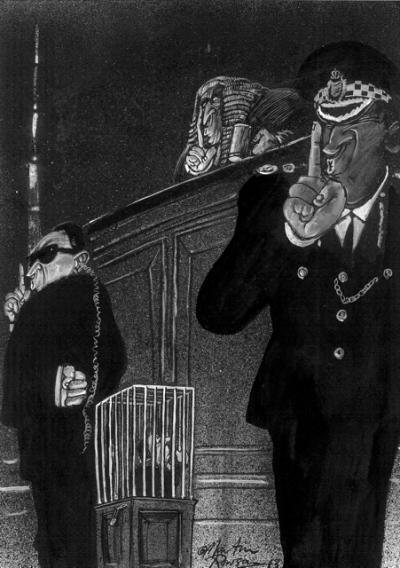

Thanks to Simon Crowther for his assistance with an early draft of this article, and to Martin Rowson for kindly providing the image.

[1] Section 6(11) “relevant civil proceedings” means any proceedings (other than proceedings in a criminal cause or matter) before—

(a)the High Court,

(b)the Court of Appeal,

(c)the Court of Session, or

(d)the Supreme Court,

[2] Section 6(11)

[3] “Belhaj says he was blindfolded, hooded, forced to wear ear defenders, and hung from hooks in his cell wall for what seemed to be hours. He says he was severely beaten. The ear defenders were removed only for him to be blasted with loud music, he says, or when he was interrogated by his US captors.” http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2012/apr/08/special-report-britain-rendition-libya

[4] http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-16804656

[4a] Section 6 “(3)The court may make such a declaration if it considers that the following two conditions are met.

(4)The first condition is that—

(a)a party to the proceedings would be required to disclose sensitive material in the course of the proceedings to another person (whether or not another party to the proceedings), …

(5)The second condition is that it is in the interests of the fair and effective administration of justice in the proceedings to make a declaration.”

[5] Section 6(6) “The two conditions are met if the court considers that they are met in relation to any material that would be required to be disclosed in the course of the proceedings (and an application under subsection (2)(a) need not be based on all of the material that might meet the conditions or on material that the application would be required to disclose.)”

[6] Section 8(2) “Rules of court relating to section 6 proceedings must secure that provision to the effect mention in subsection (3) applies in cases where a relevant person –

(b) is required to provide another party to the proceedings with a summary of material that is withheld, but elects not to provide the summary. [emphasis added]

Section 8(1) Rules of court relating to any relevant civil proceedings in relation to which there is a declaration under section 6 must secure –

(b) that such an application is always considered in the absence of every other party to the proceedings (and every other party’s legal representative).

(b) that such an application is always considered in the absence of every other party to the proceedings (and every other party’s legal representative)” [emphasis added]

[7] ‘"I thought: 'This is it.' I thought I would never see my husband again ... They took me into a cell, and they chained my left wrist to the wall and both my ankles to the floor. I could sit down but I couldn't move. There was a camera in the room, and every time I tried to move they rushed in. But there was no real communication. I wasn't questioned." Bouchar found it difficult to comprehend how she could be treated in this way: she was four-and-a-half months pregnant. "They knew I was pregnant," she says. "It was obvious." She says she was given water while chained up, but no food whatsoever. She was chained to the wall for five days.’ http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2012/apr/08/special-report-britain-rendition-libya

<[9] Section 6(10)(a) Rules of court must make provision –

(c) Requiring a person, before making an application under subsection (2)(a), to give notice of the person’s intention to make an application to every other person entitled to make such an application in relation to the relevant civil proceedings.

Section 9(3) “The ‘appropriate law officer’ is –

(a) In relation to proceedings in England and Wales, the Attorney General,”

[12] Section 11(2)(d) “Rules of court relating to section 6 proceedings may make provision –

(d) enabling the proceedings to take place without full particulars of the reasons for decisions in the proceedings being given to a party to the proceedings (or to any legal representative of that party)”

[13] http://www.reprieve.org.uk/press/2012_10_10_libyan_renditions_first_evidence/

[14] http://www.independent.ie/world-news/europe/mi5-allegedly-applies-for-secret-court-session-after-ira-informant-sues-for-being-denied-protection-29245944.html

[15] Neither Just Nor Secure – The Justice and Security Bill, Anthony Peto QC and Andrew Tyrie MP http://www.cps.org.uk/files/reports/original/130123103140-neitherjustnorsecure.pdf page 46

[16] Section 6(11) ‘“sensitive material” means material the disclosure of which would be damaging to the interests of national security.’

[17] Ibid page 47

[18] Neither Just Nor Secure – The Justice and Security Bill, Anthony Peto QC and Andrew Tyrie MP http://www.cps.org.uk/files/reports/original/130123103140-neitherjustnorsecure.pdf page 47

[18a] Section 13(2)

[19] Section 12(4)

[20] Section 12

[21] Section 12(3)

[22] http://www.independent.ie/world-news/europe/mi5-allegedly-applies-for-secret-court-session-after-ira-informant-sues-for-being-denied-protection-29245944.html

[23] http://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/mi5-allegedly-applies-for-secret-court-session-after-informant-sues-for-being-denied-protection-8605107.html

http://www.guardian.co.uk/politics/2013/may/21/abdel-hakim-belhaj-torture-secret-court?INTCMP=SRCH

[24] https://terrorismlegislationreviewer.independent.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/memorandum-for-jchr1.pdf

Read more

Get our weekly email

Comments

We encourage anyone to comment, please consult the oD commenting guidelines if you have any questions.