We recently made the case against a proposal to institute a "sender-pays" rule for Internet interconnection. The idea was submitted by European telecom incumbents and it's under discussion at this week's International Telecommunications Union confab in Dubai. Telecom incumbents love this because it could force Google, Netflix, and other major Internet services to pony up more cash. They argue they need these revenues to fund network upgrades and keep the Internet working smoothly.

A new study from the Mercatus Center at George Mason University, a libertarian think tank, casts doubt on this argument. There has never been a sender-pays Internet, so we can't be sure what it would look like. But the international telephone network does operate on a sender-pays model. And Mercatus economist Eli Dourado realized this system could provide insights about how the same billing scheme might work online.

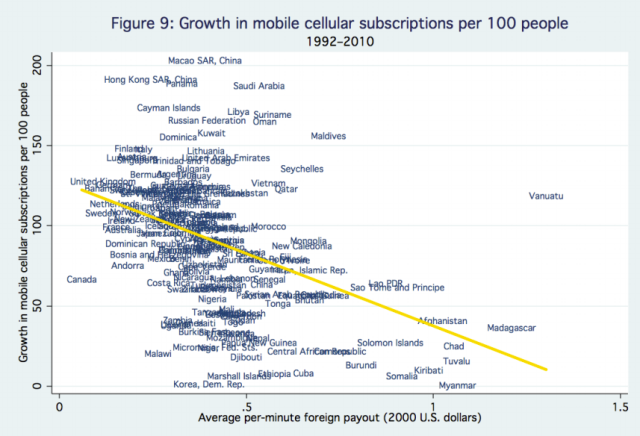

To do this, he collected statistics about international calling rates from the United States, as well as statistics measuring the growth of various nations' telecommunication sectors. If the advocates of sender-pays were right, we might expect countries with high long-distance calling rates to experience faster development of their communications networks than countries with low rates.

Surprisingly, Dourado found just the opposite:

Dourado charted international billing rates against four statistics that measure the development of telecommunications networks: fixed telephone lines per 100 people, mobile subscribers per 100 people, Internet users per 100 people, and broadband subscribers per 100 people. Dourado found little correlation between long distance rates and fixed telephone line construction. For the other three variables, he found a negative correlation. The higher a nation's long-distance rates were, the slower the pace of progress in its telecommunications sector.

Of course, correlation is not causation. The observed correlation could be based on other factors, such as a country's average income or its region of the world. But Dourado found that even after controlling for these factors, there was an inverse correlation between long-distance billing rates and telecommunications development. In short, when you give a telecommunications firm more money, there's no guarantee it will invest the cash in improving its network.

The paper also considers the possibility that causation could run in the opposite direction: maybe network upgrades make lower rates possible. To check this possibility, he re-ran his regressions on a year-to-year basis, incorporating a lag to reflect the fact that one year's higher rates could lead to higher investment in subsequent years. "If high rates today are used to fund expansion in the future, then lagged values of the rate coefficient should be positive—that is, high rates today should correlate with high growth a few years from now," Dourado wrote.

Yet even after making these adjustments, the correlations were still negative. The more expensive it was to make long distance calls to a nation, the more slowly its telecommunications sector developed.

"My results contradict the hypothesis that the ability to charge more for international Internet traffic is all that is needed to build out telecommunications infrastructure in poor countries," Dourado concludes. "High international telephone collection rates have not led to greater buildout and adoption of telecommunications infrastructure in the past two decades. It seems unlikely, therefore, that adopting a sender-pays model for Internet traffic would increase buildout of Internet infrastructure today."

Rather, Dourado suggests the quality of a nation's telecommunications network is dependent on the quality of its domestic institutions. Some countries have telecommunications industries that efficiently put new revenues to work on network improvements. Other countries have corrupt or incompetent telecommunications incumbents that will upgrade their networks slowly no matter how much money they're given. He argues that regulatory reforms, not more cash, are needed to improve global network quality.

Disclosure: The Mercatus Center paid me to contribute a chapter to a new book on copyright reform. Readers can view my full disclosure statement here.

reader comments

49