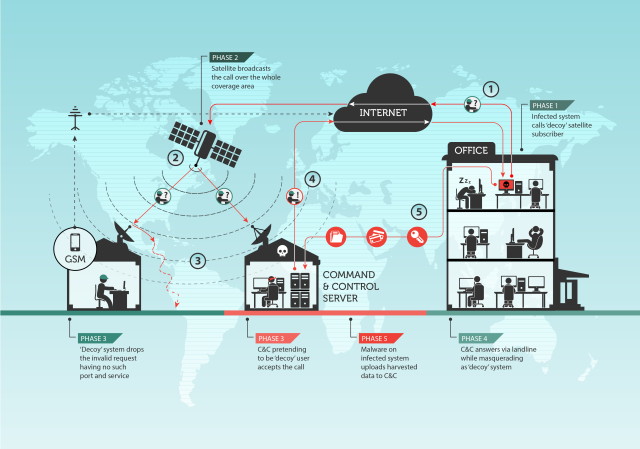

One of the world's most advanced espionage groups has already been caught unleashing an extremely stealthy trojan for Linux systems that for years siphoned sensitive data from governments and pharmaceutical companies around the world. Now researchers have discovered a highly unusual method that members of the so-called Turla group used to cover their tracks. They hijacked satellite-based Internet links to communicate with command and control servers.

Most available satellite-based Internet remains almost as limited now as when it was introduced two decades ago. It's slow and provides users only with a unidirectional download link. But there's something about the connections that made them highly attractive to Turla members: most satellite links are unencrypted and can be intercepted by anyone within a radius of more than 600 miles. That means a connection between someone located in, say, a remote location in Africa and a satellite-based ISP can be monitored or even hijacked by an attacker.According to research published Wednesday by researchers from Moscow-based security firm Kaspersky Lab, that's precisely what Turla members did. The Russian-speaking hackers reserved the method only for their highest-profile targets, and even then used it only during advanced stages of an espionage campaign. According to Kaspersky Lab Senior Security Researcher Stefan Tanase, here's how they did it:

To hijack satellite DVB-S links, one needs the following:

- A satellite dish—the size depends on geographical position and satellite

- A low-noise block downconverter (LNB)

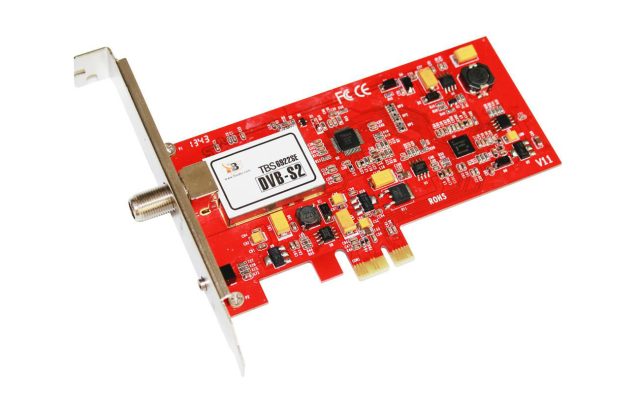

- A dedicated DVB-S tuner (PCIe card)

- A PC, preferably running Linux

While the dish and the LNB are more or less standard, the card is perhaps the most important component. Currently, the best DVB-S cards are made by a company called TBS Technologies. The TBS-6922SE is arguably the best entry-level card for the task.

The TBS card is particularly well-suited to this task because it has dedicated Linux kernel drivers and supports a function known as a brute-force scan, which allows wide-frequency ranges to be tested for interesting signals. Of course, other PCI or PCIe cards might work as well, while in general, the USB-based cards are relatively poor and should be avoided.

Unlike full duplex satellite-based Internet, the downstream-only Internet links are used to accelerate Internet downloads and are very cheap and easy to deploy. They are also inherently insecure and use no encryption to obfuscate the traffic. This creates the possibility for abuse.

Companies that provide downstream-only Internet access use teleport points to beam the traffic up to the satellite. The satellite broadcasts the traffic to larger areas on the ground, in the Ku band (12-18Ghz), by routing certain IP classes through the teleport points.

The Turla attackers listen for packets coming from a specific IP address in one of these classes. When certain packets—say, a TCP/IP SYN packet—are identified, the hackers spoof a reply to the source using a conventional Internet line. The legitimate user of the link just ignores the spoofed packet, since it goes to an otherwise unopened port, such as port 80 or 10080. With normal Internet connections, if a packet hits a closed port, the end user will normally send the ISP some indication that something went wrong. But satellite links typically use firewalls that drop packets to closed ports. This allows Turla to stealthily hijack the connections.

The hack allowed computers infected with Turla spyware to communicate with Turla C&C servers without disclosing their location. Because the Turla attackers had their own satellite dish receiving the piggybacked signal, they could be anywhere within a 600-mile radius. As a result, researchers were largely stopped from shutting down the operation or gaining clues about who was carrying it out.

"It's probably one of the most effective methods of ensuring their operational security, or that nobody will ever find out the physical location of their command and control server," Tanase told Ars. "I cannot think of a way of identifying the location of a command server. It can be anywhere in the range of the satellite beam."

Listing image by Alan Levine

reader comments

56