Sitting in a cafe the other day, I listened to two people doing norovirus one-upmanship. I had it for two days and it was awful, said a young woman. Oh, I felt terrible, said the barista, but I came into work – displaying the same casual attitude to the illness that has seen thousands struggle into work, or keep up social rounds, despite still being infectious.

More than a million people in the UK are thought to have had it. Schools have been shut, and even an oil rig. And yet, despite being as regular as floods and Christmas, every year there is surprise that norovirus is back – and so successfully. I said nothing, while looking at my coffee cup with more suspicion than before, and considered our delusions. That young man came to work because he couldn't believe he was a danger. Was it because he couldn't see the infection? Was it because "health and safety" has become a hackneyed joke, rather than the two greatest achievements of modern life?

He has grown up certain to survive past the age of five without dying from diarrhoea or malaria or pneumonia, as millions of the world's toddlers still do. He safely made it to adulthood without getting rickets or scurvy or polio or any of the communicable diseases that have been made to disappear – with huge effort – from the wealthier world. He was buffered and warmed by a delusion of inviolability, so that what he cannot see is no threat, so that food and water are always benign. He was so healthy and so safe that he dismissed the dangers of infecting others. He was wrong to do so.

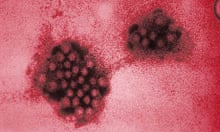

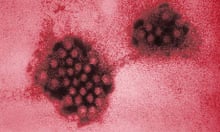

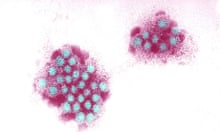

We do live with an extraordinarily elevated level of safety now. We are fortunate, but we are also unprepared. Norovirus is a particularly canny creature. It is economical in its contagion: just a handful of virus particles are required to spread infection. It is hardy, and can survive on coffee-cups, on plastic bags, in droplets that are expelled with a toilet flush if the seat is left open. It does not seem to inspire fear, despite the numbers infected, because it rarely kills. It even has, in "winter vomiting bug", an anodyne pet name. But we should pay attention to it because of what it means about us and our future relationship with microbiological adversaries.

Norovirus travels. Bugs travel. They travel to oil rigs; they travel on international aeroplanes. When Sars spread across the world in 2003, it wasn't by ship, as cholera spread in 1831, when the citizens of England waited in terror for the bug to arrive from Hamburg, bringing death. It travelled more quickly and beyond the reach of containment, because it flew business and economy. Bugs are global now because we have made them so. Of course, most of us are unlikely to die of norovirus. But in the US, where there are usually 20m cases of the illness a year, deaths in the elderly and immune-compromised have risen alarmingly.

Quarantine sounds like such an old-fashioned word, from an era of Typhoid Mary and locked wards. But more self-imposed quarantine wouldn't go amiss; more baristas who stay home; more coffee cups that remain untouched by those malign particles. There is a phrase used in the field of sanitation that is powerfully memorable: a fly, they say in Bangladesh, is deadlier than a thousand tigers. The fly is deadlier because of the toxic bugs on its feet and because billions of humans, through their behaviour, give those bugs life and longevity. (Behind our assumptions about our health and safety lie plenty of mistaken ones about our hygiene, too.)

We should be more respectful of our microbiological adversaries, whether they have pet names or not. They've certainly earned the right to our wariness.