Two researchers at Georgia Tech can tell you exactly how American ISPs shape Internet traffic, and which ones do so. Bottom line: of the five largest Internet providers in the country, the three cable companies (Comcast, Time Warner, Cox) employ shaping while the telephone companies (AT&T, Verizon) do not—though that fact is less significant for the user experience than it might first sound.

Partha Kanuparthy and Constantine Dovrolis wanted to measure Internet shaping, so they built a tool called ShaperProbe to do so. The tool relies on users from around the country running tests in which the user's computer transmits data at a constant bit rate, while ShaperProbe's 48 Linux-based server instances watch incoming traffic to see if that rate degrades in predictable ways over time. Using the M-Lab infrastructure, ShaperProbe has collected more than 1 million trial runs from 5,700 ISPs over the last two years (run your own test).

The resulting paper (PDF) documents the first accurate attempt to “measure traffic shaping deployments on the Internet.”

Emptying the bucket

Traffic shaping hardware generally relies on the concept of a “token bucket.” Traffic management hardware will generate a digital token for each Internet user at a predetermined rate. These tokens fill a virtual token bucket; transmitting packets over the Internet removes tokens from the bucket. If the bucket empties, no more data can be transmitted until a new token is deposited.

The practical result is that the user sits down to her computer with a full token bucket and can immediately blast data through her connection as fast as the connection can go. But after some interval of time, usually measured in seconds, this sort of full-throttle data transmission empties the token bucket and the user is now limited to transmitting at the token generation rate.

ShaperProbe measures the length of time it takes for traffic shaping hardware to make a "level shift" to a slower speed limit on the line. Charting this data enough times, and from enough different users with different Internet access tiers, allowed Kanuparthy and Dovrolis to estimate the token bucket parameters—and thus to figure out exactly when and how traffic shaping kicks in for any particular ISP's speed tier.

Traffic shaping isn't necessarily some devious attempt to give users less bandwidth than expected; it can also be used to let users transmit "bursty" files more quickly than their speed tier would otherwise allow, shaping them down to their chosen tier only after some set amount of time. This is how Comcast markets its "PowerBoost" technology, for instance.

The use of shapers can also be dictated by the underlaying access tech. The researchers note that DSL providers can “dynamically change link capacity instead of shaping, while a cable provider is more likely to shape since DOCSIS provides fixed access capabilities." It can also be applied to the entire Internet link or more narrowly to specific kinds of traffic— which, as the researchers note, is "relevant to the ‘heated’ network neutrality debate."

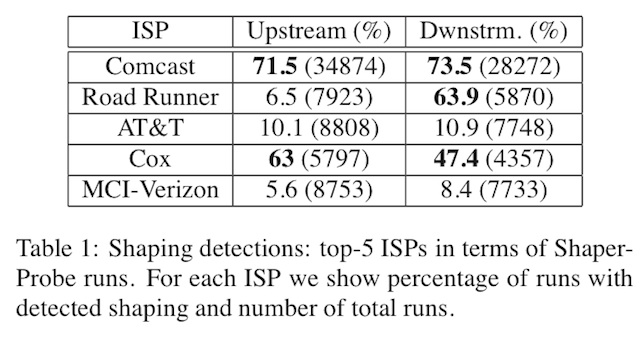

The research shows that Comcast, Road Runner (from Time Warner Cable), and Cox all use downstream shaping—but only Comcast and Cox also use upstream shaping. Neither AT&T nor Verizon shape in either direction.

The research is separate from a recent million-dollar Google grant to other Georgia Tech researchers looking at ways to detect Internet censorship or throttling, but it was funded by a previous 2009 Google grant. It also runs on the Google-funded M-Lab hardware network. As Google noted in its most recent Georgia Tech grant, it hopes to create tools to that "users could determine whether their ISPs are providing the kind of service customers are paying for, and whether the data they send and receive over their network connections is being tampered with by governments and/or ISPs."

reader comments

55