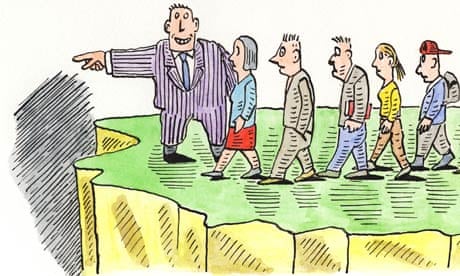

The phrase "graduate without a future" came into my head while I was lecturing students in the politics society at Birmingham University. I drew a notional graph of expectations, curving up: here's your income at 21, then you get rising wages, rising house prices once you're on the ladder; your pension pot grows and at the end of the curve you're comfortable and there's a welfare state to protect you if things go wrong.

That was the old curve. Then I drew the new one. It curves down: wages don't rise; you can't get on the property ladder. Fiscal austerity eats into your disposable income. You are locked out of your firm's pension scheme; you will wait until your late 60s for retirement. And if it all goes wrong, it's touch and go whether the welfare safety net will still be there.

By now some of the audience were getting neck ache from the vigorous nodding. This generation of young, educated people is unique – at least in the post-1945 period: a cohort who can expect to grow up poorer than their parents. They've seen a massive leap in youth unemployment: 19% in the UK, 17% in Ireland, 50% in Spain and Greece. But they've also lived through a revolution in technology and communications that was supposed to empower the young.

In grasping the basic inequity of the situation, students themselves were ahead of the journalists and commentators. As early as 2009 students in the self-designated "Research and Destroy" collective at the University of California, Santa Cruz, issued their famous "Communique from an absent future": "'Work hard, play hard' has been the over-eager motto of a generation in training for … what? – drawing hearts in cappuccino foam … We work and we borrow in order to work and to borrow. And the jobs we work toward are the jobs we already have. What our borrowed tuition buys is the privilege of making monthly payments for the rest of our lives."

As the Arab spring exploded around us – and unrest continues from Athens to Quebec – this sociological type has been central. The graduate who has been denied the leisurely, liberal education of their parents' generation, but instead has been faced, almost since puberty, with a battery of psychometric tests, exhortations to excellence, and life-limiting vocational choices.

When I was at university (Sheffield, 1978-81) I found time to play in a band, picket a steelworks, occupy several buildings, write embarrassingly bad fiction, switch courses and demand the creation of a special dual degree to suit my life's purpose. "You can do it as long as you don't tell anybody else it exists," my professor told me. Tuition was free. There was a grant you could live on as long as you did not stray from drink to class A drugs, and in the holidays I had a factory job that paid nearly as much as my dad's real factory job did.

It's embarrassing to say this to a generation where individual tuition has become a privilege; where non-examinable knowledge is perceived as a waste of time; where every thesis and dissertation must begin with a mind-numbing rehash of existing knowledge, written to a formula as rigid as that demanded by the Qing-era Chinese civil service. But here goes: the past was better.

For the future to be better, we need to break with an economic model that no longer works. For the graduate without a future is a human expression of an economic problem: the west's model is broken. It cannot deliver enough high-value work for its highly educated workforce. Yet the essential commodity – a degree – now costs so much that it will take decades of low-remunerated work to pay for it.

As I've toured universities, squats and occupation camps to talk about the roots of the crisis there have been times when I've had to say: "The term graduate without a future does not mean you literally have no future." Because the prevalent psychology among young people has become dangerously nihilistic, even for the activists.

If you follow their mood swings on Twitter, you see the original Egyptian bloggers in a state of despair now, faced with the victory of the Islamists in the presidential election. You see the Bahraini youth recounting bitter episodes of injustice, beatings, sexual assaults.

As for the Occupy generation, there are nights when my Twitter feed is filled with cheerfully recounted news of self-destructive lifestyles, interspersed with bursts of pepper spray and court appearances.

As youth unemployment hits 50% in the stricken countries of peripheral Europe, and the crisis drags from one year to the next, there is an air of softness creeping into young adult culture. A dreamy awareness that things could drift like this for quite some time; the adoption of fashion choices that suggest endless enforced leisure – the tracksuit bottoms of the scally in Britain, the shorts and beard of the slacktivist in south Europe and southern California.

The anti-leadership ideal, the structurelessness that defined the struggles of 2009-11, is beginning to grate as well. Since the protest movements are geared to avoid the emergence of leaders, all that happens is that this generation is forced to assemble around the podiums of existing scribes and prophets: the physical grammar of those lectures by Žižek, Chomsky, David Harvey, Samir Amin – a man with a grey beard pontificating to 21-year-olds – becomes hard to watch.

There are positives. As I've met young activists keen to tell me what their latest protest action's going to be, there is nearly always another story: they've set up an online magazine. No, it's not a collective, it's a business. They've set up a cafe, or a theatre group, or – as in the Andalusian farm I visited – seized abandoned land and planted vegetables.

All those tests, drills, teach-to-exam lectures, and the relentless vocationality of education, has made this generation highly entrepreneurial.

Rachel Rosenfelt, the 23-year-old New Yorker who set up an online publication called The New Inquiry, sums it up: "there is surplus population" of talented young people, with precisely skills a 21st-century infocapitialism would need if it took off. But it is stalled.

Just as they created, out of nothing, forms of protest that broke with the past, this generation is creating forms of business and commerce, literature and art, that live in the cracks left by shrinking GDP and collapsing credit.

And they know more: they are not surprised when those in power betray, or when a long-cherished theory is disproved. This is the first generation able to treat knowledge like software: available for upload, use, upgrade and eventual disposal. They are able to start with levels of knowledge previous generations had to learn through a long process of ingestion and skill acquisition. Now all they need is for the economic model to catch up with the human potential technology has created.

As the years have ticked by – with the freshmen of the Lehman Brothers year now into their second year as postgrads, or second year on the dole – the realisation has dawned on the graduate without a future: you have to make the future yourself. And if you look hard enough – look past the unkempt beards and the party-smeared mascara – they are having a pretty good go at it.