What Was Reddit Troll Violentacrez Thinking?

Little of what Violentacrez told Gawker's Adrian Chen can help us understand what makes someone troll.

By now you have probably read Adrian Chen's substantial and disturbing profile of Michael Brutsch, aka Violentacrez, aka "The Biggest Troll on the Web." Among Brutsch's "accomplishments": establishing or moderating subreddits for "jailbait" (photos of scantily clad teenage girls), "creepshots" (close-ups of women's asses and breasts, taken in public), incest, and posting a photograph of a woman being brutally beaten in a subreddit called "beating women."

What goes on inside the head of Michael Brutsch or other people like him that leads to this kind of behavior? What did he think about those who were on the receiving end of his trolling?

It seems he did not think about them at all. They were completely removed from him physically, and as sociologists have shown, the greater the distance between us and our victims, the easier it may be to cause pain. This is one proposed explanation for an escalation in intensity in warfare, or an eagerness to go pursue war, as weapons technology has increased the distance between fighting parties. Likewise, in Stanley Milgram's famed experiments, the willingness of people to willingly shock other people decreased dramatically as subjects came into closer and closer contact with their supposed victims. When the shocker and the shockee were placed in the same room and could see one another, obedience dropped from 65 to 40 percent. When they were made to be in physical contact, obedience fell to 30 percent, and so on.

But online -- particularly in a world that thrives on anonymity -- people are not in proximity with one another, it may in some ways be harder to make the thinking leap, to bring the object of your trolling into your mind. The trolled are not people; they are usernames. They do not feel or experience pain; it may be hard to imagine them reading your words or seeing the picture you posted at all.

A recent essay in The Guardian seems to support this theory. In the story, Irish writer Leo Traynor manages to identify a troll who has been horribly, brutally harassing him and his wife for years. The troll called him a "dirty fucking Jewish scumbag" and mailed him a Tupperware full of ashes with the note, "Say hello to your relatives from Auschwitz."

With the help of an "IT genius" friend, Traynor tracks down the hacker: It's the son of another friend. Traynor calls the friend and they decide to set up a meeting with the son and both of his parents. As they sit down to chat over tea, Traynor tells them all about harassment, showing them pictures of the ashes and screenshots of the offending tweets.

"I told them of how I'd become so paranoid that I genuinely didn't know who to trust anymore," Traynor writes. "I told them of nights when I'd walked the rooms, jumping at shadows and crying over the sleeping forms of my family for fear that they would suffer because of me. Then it happened ... The Troll burst into tears. His dad gently restraining him from leaving the table."

What Traynor did was to force his troll to *think* about his actions, not just perform them because of the norms of a subculture.

What happened when Adrian Chen confronted Brutsch looks quite different: Brutsch didn't so much cry as offer one mild, unilluminating cliche after the other. His response to people who were offended by that photo? "People take things way too seriously around here." In defending his actions: "I got the freedom to talk about my personal life, my personal feelings... I'm sure there's more than one person in this building who's a pervert," he told Chen.

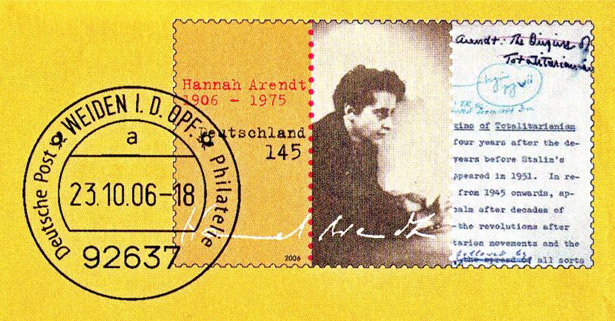

This utter void of introspection on the part of the troll made me think of an essay by Hannah Arendt, "Thinking and Moral Considerations," which she wrote for W.H. Auden in 1971. In it, she considers what she had witnessed years earlier, as Eichmann stood trial in Jerusalem. "The only specific characteristic one could detect in his past as well as in his behavior during the trial and the preceding police examination was something entirely negative: It was not stupidity but a curious, quite authentic inability to think," she wrote.*

Eichmann, like Brutsch, spoke in a series of linked phrases that explained little. "He knew that what he had once considered his duty was now called a crime, and he accepted this new code of judgment as though it were nothing but another language rule. To his rather limited supply of stock phrases he had added a few new ones, and he was utterly helpless only when he was confronted with a situation to which none of them would apply, as in the most grotesque instance when he had to make a speech under the gallows and was forced to rely on cliches used in funeral oratory which were inapplicable in his case because he was not the survivor." She continued, "Cliches, stock phrases, adherence to conventional, standardized codes of expression and conduct have the socially recognized function of protecting us against reality, that is, against the claim on our thinking attention which all events and facts arouse by virtue of their existence."

What Arendt theorized is that a conscience is the byproduct of the process of thinking -- that thinking itself enables the power of judgment, to discern "right from wrong, beautiful from ugly."

Part of how Arendt understood thinking is particularly relevant to a consideration of the online behavior of trolling, in which any prey is by nature at a distance from the predator. "Thinking," she wrote, "always deals with objects that are absent, removed from direct sense perception." Once you are thinking about something, it is no longer the object itself, but the object in your mind. In that sense, thinking somehow vanquishes distance, forcing you, the thinker, to come into contact with the thing (or person) you are thinking about. And, perhaps, through that, a natural consequence is empathy, even just a drop of it.

That seems to be what happened when Traynor took his troll to tea: Traynor and his pain were right there, inescapable, and the reaction of the kid was maybe the only one that avoids the empty statements of a Brutsch or an Eichmann: He cried. Because in truth, there are no sentences that can justify the behavior of a troll, or that can explain it and make it make sense. The only response that demonstrates some closing of the gap between troll and trolled, that shows that the pain one has caused has finally entered one's thoughts, is an emotional reaction, one that says: I get it. I'm human like you.

* I by no means intend to make a comparison between the crimes of Eichmann and the trolling of Brutsch. Rather, the conceit here is that Arendt's observations can be extended far beyond the particular example of Eichmann to many other instances of human action that betray a callous disregard for the lives of others.