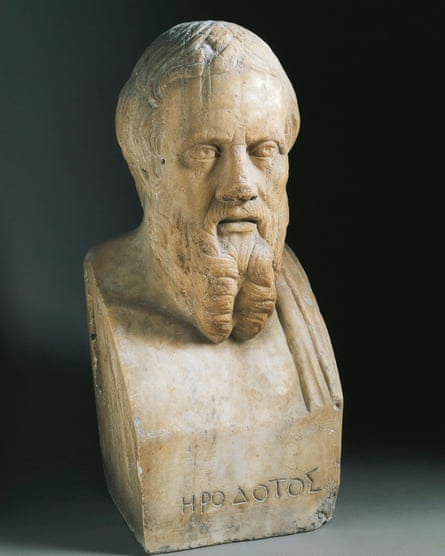

In the fifth century BC, the Greek historian Herodotus visited Egypt and wrote of unusual river boats on the Nile. Twenty-three lines of his Historia, the ancient world’s first great narrative history, are devoted to the intricate description of the construction of a “baris”.

For centuries, scholars have argued over his account because there was no archaeological evidence that such ships ever existed. Now there is. A “fabulously preserved” wreck in the waters around the sunken port city of Thonis-Heracleion has revealed just how accurate the historian was.

“It wasn’t until we discovered this wreck that we realised Herodotus was right,” said Dr Damian Robinson, director of Oxford University’s centre for maritime archaeology, which is publishing the excavation’s findings. “What Herodotus described was what we were looking at.”

In 450 BC Herodotus witnessed the construction of a baris. He noted how the builders “cut planks two cubits long [around 100cm] and arrange them like bricks”. He added: “On the strong and long tenons [pieces of wood] they insert two-cubit planks. When they have built their ship in this way, they stretch beams over them… They obturate the seams from within with papyrus. There is one rudder, passing through a hole in the keel. The mast is of acacia and the sails of papyrus...”

Robinson said that previous scholars had “made some mistakes” in struggling to interpret the text without archaeological evidence. “It’s one of those enigmatic pieces. Scholars have argued exactly what it means for as long as we’ve been thinking of boats in this scholarly way,” he said.

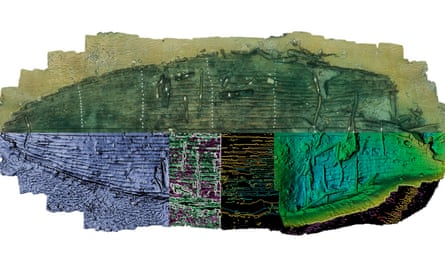

But the excavation of what has been called Ship 17 has revealed a vast crescent-shaped hull and a previously undocumented type of construction involving thick planks assembled with tenons – just as Herodotus observed, in describing a slightly smaller vessel.

Originally measuring up to 28 metres long, it is one of the first large-scale ancient Egyptian trading boats ever to have been discovered.

Robinson added: “Herodotus describes the boats as having long internal ribs. Nobody really knew what that meant… That structure’s never been seen archaeologically before. Then we discovered this form of construction on this particular boat and it absolutely is what Herodotus has been saying.”

About 70% of the hull has survived, well-preserved in the Nile silts. Acacia planks were held together with long tenon-ribs – some almost 2m long – and fastened with pegs, creating lines of ‘internal ribs’ within the hull. It was steered using an axial rudder with two circular openings for the steering oar and a step for a mast towards the centre of the vessel.

Robinson said: “Where planks are joined together to form the hull, they are usually joined by mortice and tenon joints which fasten one plank to the next. Here we have a completely unique form of construction, which is not seen anywhere else.”

Alexander Belov, whose book on the wreck, Ship 17: a Baris from Thonis-Heracleion, is published this month, suggests that the wreck’s nautical architecture is so close to Herodotus’s description, it could have been made in the very shipyard that he visited. Word-by-word analysis of his text demonstrates that almost every detail corresponds “exactly to the evidence”.

Ship 17 is the 17th of more than 70 vessels dating from the 8th to the 2nd century BC, discovered by Franck Goddio and a team – including Belov - from the European Institute for Underwater Archaeology during excavations in Aboukir bay, with which the Oxford Centre is involved.