'Twisted light' data-boosting idea sparks heated debate

- Published

- comments

An idea to vastly increase the carrying capacity of radio and light waves has been called into question.

The "twisted light" approach relies on what is called light's orbital angular momentum, which has been put forth as an unexploited means to carry data.

Now a number of researchers, including some formally commenting in New Journal of Physics, say the idea is misguided.

Responding in the same journal, the approach's proponents insist the idea can in time massively boost data rates.

That promise is an enticing one for telecommunications firms that are running out of "space" in the electromagnetic spectrum, which is increasingly crowded with allocations for communications, broadcast media and data transmission.

So others are weighing in on what could be a high-stakes debate.

"This would be worth a Nobel prize, if they're right. Can you imagine, if all communications could be done on one frequency?" asked Bob Nevels of Texas A&M University, a former president of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers' Antennas and Propagation Society.

"If they've got such a great thing, why isn't everyone jumping up and down? Because we know it won't work," he told BBC News.

The disagreement in New Journal of Physics provides a window on the time-honoured practice of open debate in academic journals (as opposed to the increasingly widespread approach of debating issues before they are even formally published): a kind of "he says, she says" with references.

Wiggle room

The principle behind the idea is fairly simple. Photons, the most basic units of light, carry two kinds of momentum, a kind of energy-of-motion.

One, spin angular momentum, is better known as polarisation. Photons "wiggle" along a particular direction, and different polarisations can be separated out by, for example, polarising sunglasses or 3D glasses.

But they also carry orbital angular momentum - in analogy to the Earth-Sun system, the spin angular momentum is expressed in our planet spinning around its axis, while the orbital angular momentum manifests as our revolution around the Sun.

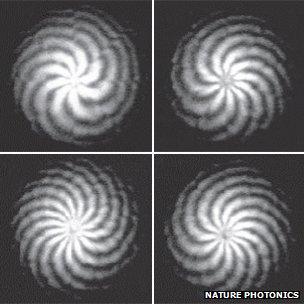

The new technique aims to exploit this orbital angular momentum, essentially encoding more data as a "twist" in the light waves.

That the phenomenon exists is not in question - it has been put to use recently in studying black holes, for example.

What makes the current debate devilishly complex is arguing whether experiments by Bo Thide of the Swedish Institute of Space Physics and colleagues really do use and benefit from it.

The team has carried out very public demonstrations of the idea, sending data across a Venice lagoon in a test first described in a New Journal of Physics article. But even before that article made it to press, other researchers were questioning the approach's validity.

In a paper in IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation, Lund University's Ove Edfors and Anders Johansson argued that what was going on was a version of "multiple input, multiple output" - or Mimo - data transmission, a technique first outlined in the 1970s.

"I've been trying to have a discussion with these guys, asking for arguments - because all the arguments they have put forward have been perfectly explainable by standard theories," Prof Edfors told BBC News.

"What I get back is 'you don't understand, you're not a physicist', and I say 'well, try to convince me'."

Julien Perruisseau-Carrier at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Lausanne, Switzerland (EPFL), and colleagues make much the same argument in their comment paper published this week. But it seems clear that the controversy arises as a conflict between the disciplines of physics and engineering.

"These people are physicists, they have their own research," Prof Perruisseau-Carrier told BBC News. "But the authors are trying to spin off some of their work into a telecommunications issue.

"The fact is they didn't understand that what they were doing, as we explained, is a subset of something very well-known and documented."

Detractors argue that the demonstrations so far have only used two "modes" to transmit information, perfectly replicating a Mimo setup - and that if Prof Thide and colleagues try to extend the work - to the promised tens or hundreds of possible modes, they will fail.

For his part, Prof Thide insists that it is the engineers who have misunderstood.

"The typical wireless engineer, even if a professor, doesn't know anything about angular momentum," he told BBC News.

"The points made by these people... are in contradiction to each and every textbook there is in electrodynamics. This is not something invented by us, something we found out on a coffee break - this is on solid theoretical foundations going back through several Nobel prizes."

But the groundswell of resistance to the technique seems to be growing. Prof Nevels and his Texas A&M colleague Laszlo Kish have published a paper in PLOS ONE that they believe is the simple, final proof of its impossibility - and more academics are signing on as co-authors.

Prof Perruisseau-Carrier says that the idea will prove itself valid or otherwise soon enough.

"They mentioned they have some contact with telecoms companies - we were very happy to see that. There's no doubt that as soon as they defer to a real expert, that people will notice [that the idea is flawed]," he said.

"We are convinced that this will not go anywhere."

- Published25 June 2012

- Published2 March 2012

- Published14 February 2011