In 1972, the Court of Customs and Patent Appeals (CCPA) got a new chief judge named Thomas Markey. At Markey's investiture ceremony, patent attorney Donald Dunner spoke of the "anguish of the patent bar about the treatment of patents in various federal courts." The CCPA, a DC-based court that heard appeals from the US Patent & Trademark Office, was considered to be relatively pro-patent—but other federal appeals courts had jurisdiction over actual patent lawsuits and tended to be friendlier to patent defendants. Even worse, in Dunner's view, the Supreme Court itself seemed unfriendly to patent holders.

This sad state of affairs made it a bad time to be a patent attorney. Because patents were frequently invalidated by the courts, companies filed many fewer applications for them than they do today. Patents were seen as a backwater in the legal profession. Dunner urged Markey to inspire "his associates on this bench to spread the patent gospel to their sisters and brothers on the other federal benches."

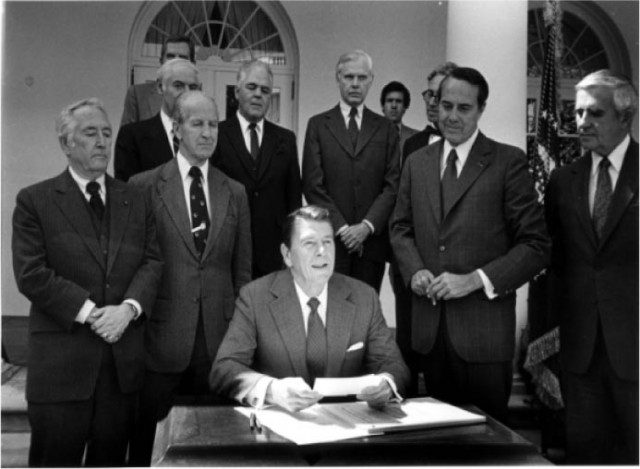

A decade later, the patent bar's anguish would turn to joy as Congress merged the CCPA with another court to create the US Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit. The Federal Circuit would be just as patent-friendly as the CCPA, but unlike its predecessor, the Federal Circuit was handed jurisdiction over all patent appeals, including the lawsuits that had previously been handled by other courts. On October 1, 1982, Judge Markey became the chief judge of the new court and set to work to remake patent law.

No institution is more responsible for the recent explosion of patent litigation in the software industry, the rise of patent trolls, and the proliferation of patent thickets than the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit. The patent court's thirtieth birthday this week is a good time to ask whether it was a mistake to give the nation's most patent-friendly appeals court such broad authority over the patent system.

The patent lawyers' court

Patent scholars Adam Jaffe and Josh Lerner tell a story in their 2004 book Innovation and Its Discontents that illustrates the problem Congress was trying to solve with the creation of the Federal Circuit. Every Tuesday at noon, a crowd would gather at the patent office awaiting the week's list of issued patents.

As soon as a patent was issued, a representative for its owner would rush to the telephone and order a lawyer stationed in a patent-friendly jurisdiction such as Kansas City to file an infringement lawsuit against the company's competitors. Meanwhile, representatives for the competitors would rush to the telephone as well. They would call their own lawyers in patent-skeptical jurisdictions like San Francisco and urge them to file a lawsuit seeking to invalidate the patent. Time was of the essence because the two cases would eventually be consolidated, and the court that ultimately heard the case usually depended on which filing had an earlier timestamp.

By 1982, concerns about the lack of uniformity in patent law had become widespread. Observers were also worried that generalist judges lacked expertise to handle the complexities of patent law. And so Congress combined the CCPA with the Court of Claims (which handled lawsuits against the federal government) to create this new court, the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit.

The new court had exclusive jurisdiction over patent appeals. Patent lawsuits were still heard by trial courts across the country, but when the trial courts' rulings were appealed, they would no longer go to one of the 12 geographically-based appeals courts that handle most other appellate issues. Instead, all patent cases would be heard by the Federal Circuit.

"Effectively reversing some major precedents"

By definition, this accomplished Congress's goals of making patent law more uniform and bringing greater "expertise" to patent issues. But it had an important side effect—making the law more favorable to patent holders.

Theoretically, the pro-patent leanings of the Federal Circuit should have been checked by a more skeptical Supreme Court. In practice however, the patent court had a great deal of autonomy.

"It is not common in the life of the law in America for a lower court and a major segment of its bar to take on the nation's highest court, effectively reversing some major precedents or at least substantially mitigating their impact," notes Steven Flanders in a recent history of the patent court. "Yet this was done."

The Federal Circuit, he said, also took on "the quieter and subtler effort to re-educate trial judges throughout the judiciary, to make them friendlier to patent-holders (or at least to the system of patents) as well." (Flanders, it should be noted, is an avowed supporter of the Federal Circuit and its efforts to reshape patent law).

This dismissive attitude toward Supreme Court precedents apparently survives to this day among patent lawyers. In the wake of this year's decision limiting patents on the practice of medicine, patent attorney Gene Quinn wondered, "How long will it take the Federal Circuit to overrule this inexplicable nonsense?" Obviously, the Federal Circuit can't "overrule" a Supreme Court decision. But with enough persistence, it can, and often does, subvert the principles enunciated by the nation's highest court. And when it does so, it almost always works in the direction of making patents easier to obtain and enforce.

reader comments

170