When I was a university student in Beijing in the early ’90s, I stumbled upon an academic article by Zhao Liming, a professor at Tsinghua University’s Chinese language department, about a little-known script used only by women in a corner of the southern province of Hunan. Days after, I bought the small book she had written on the subject, Nüshu—A Surprising Discovery, and read it as fast as my eyes, and my Chinese reading skills, allowed. I was hooked: The word nüshu refers to a script used by women in Jiangyong—a small county in the province’s southernmost tip—to transcribe the local lingo. As soon as I could, I made the first of many trips there.

Women’s writing

The largest number of nüshu practitioners used to live in the village of Shangjiangxu, where young girls exchanged small tokens of friendly affection, such as fans decorated with calligraphy or handkerchiefs embroidered with a few auspicious words. Some of the script’s usages were highly ritualized: Young girls were allowed to make a full-fledged pact of closeness with one other that they were “best friends”—jiebai zimei or “sworn sisters”—a relationship that was recognized as valuable and even necessary for them in the local social system. One’s “sworn sisters” could be a group of girls, or just a single BFF, in which case they would be called laotong, or “same”—a crazy-close friendship of the kind that most girls have in their teens. In old Jiangyong, sleepovers and fun among girlfriends were approved and supervised by the whole village.

Then, one of the girls’ aunts (on the father’s side, if possible) would listen to the friends making a formal vow of loyalty to one another and would teach them how to write nüshu. When they were older, and got married into other villages, the script would help them keep in touch. Other usages, like the “Third Day Letters,” were also ritualized: the area observed the marriage custom, common in other parts of southern China, of seeing the bride return to her home village three days after the wedding, moving permanently to her married home only once she got pregnant. In Jiangyong, the bride was awaited by her friends on the third day with little booklets written in nüshu, full of standard expressions of affection and good wishes.

Being girls, in rural China, they would very rarely be taught how to read and write anything else, so, sometimes, the most literarily inclined among them used nüshu to write down their daily thoughts. Another common genre was autobiographies, traditionally written by older women who wanted to leave a trace of their experiences.

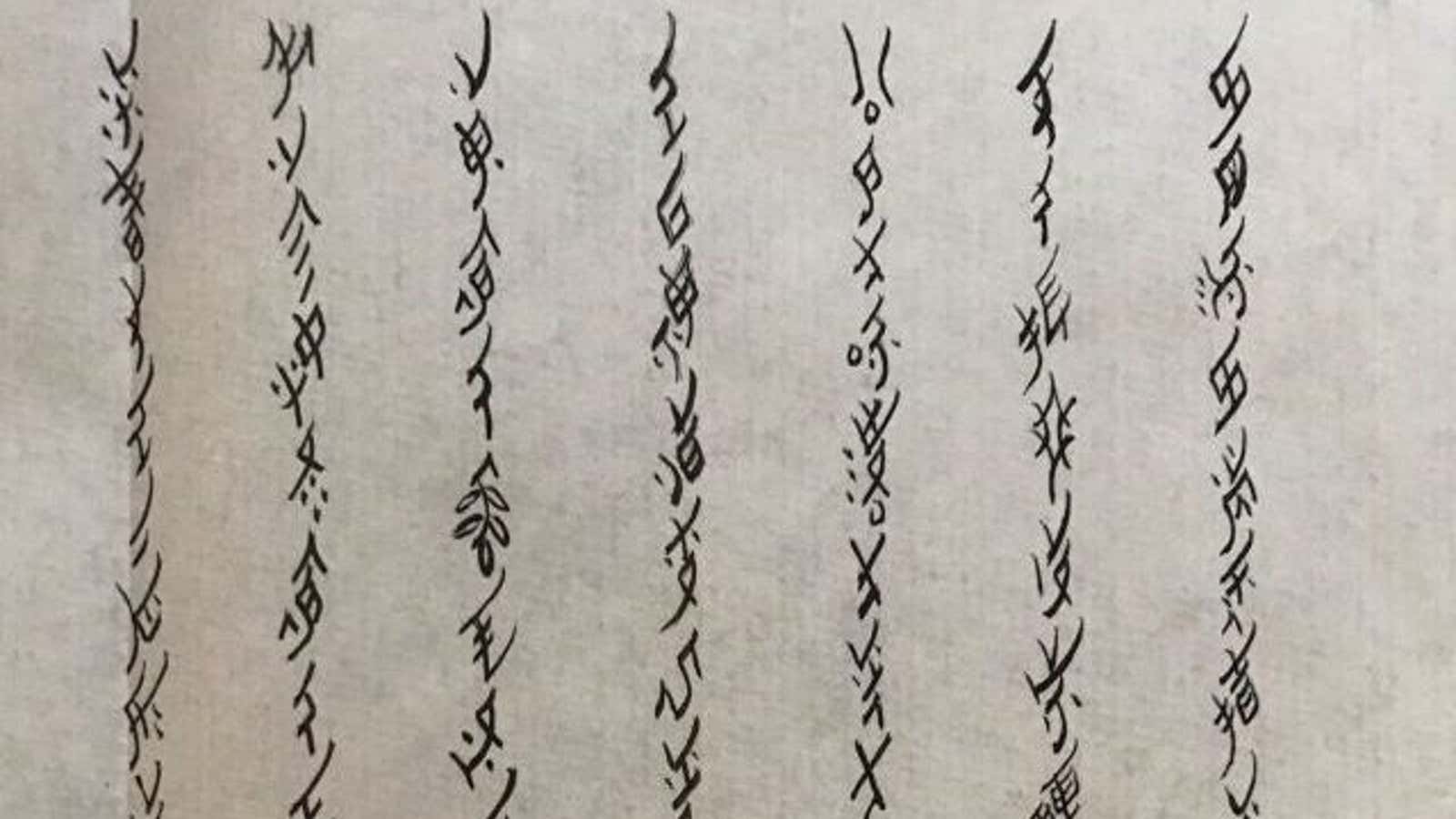

Other writings in nüshu were even more literary: Some women would copy down popular stories and legends, and there were a set of popular songs sung by women that would be transcribed, often on fans, to be used during special “nüshu days” that followed the lunar calendar, when the girls were having singing meetings in the village hall or in the fields. Nüshu is phonetic and semi-syllabic: Each grapheme (there are a few thousand) corresponds to a syllable, and, with few exceptions, its meaning is inferred by context.

Some of the women I encountered were full-fledged writers, like Yang Huanyi, whom I met in 1992, when she was in her late 80s (nobody remembered exactly when she was born.) She lived in the mountains above Jiangyong, where her husband was from, and she told me she liked to write every day. “I write what I see from the window. What I think about when I walk along these paths. How the seasons change. I wake up before everyone else, and I just sit and write for a while.” The first time we spoke she had trouble understanding my name, so she asked me to write it down—and I did so, scribbling the three characters for Lan Ruiya, my Chinese name. She looked puzzled. “What did you use male characters for?” she asked. “You should write with the women’s ones.”

When I told her that I did not know how to, that most women outside of Jiangyong did not know how to, I felt a bit guilty and looked around at those near us, hoping they would come to my rescue. They just laughed politely—at my surprise, at Yang’s look of puzzlement. I could tell that she thought it was a bit coarse, maybe even tomboy-ish of me, to just arrive and write down in normal Chinese, as if I were a man.

The women themselves, of course, didn’t call it nüshu, which literally means “women’s script” or “women’s writing,” a definition given by scholars who first approached it, during the last century. The women called it many things, including “mosquito writing,” because it is a little slanted and with long “legs,” and embroidery script.

I experienced all this with growing fascination. The usual tropes of rigid Chinese patriarchal rules for women that I had read so much about suddenly started to shift, and real life, together with regional variations on social standards, showed how China is a much more complex and varied place than any monolithic description would have us believe. But the way nüshu was being approached by the handful of Chinese academics looking into it, and, slowly, by the wider world, would be very different from how I perceived it.

A language of “sorrow”

Zhao, the professor whose work introduced me to this world, invited me to the First International Conference on Nüshu, in 1993, some months after I began visiting Shangjiangxu. The area was rather poor, and still closed to foreigners, so while my undergraduate presence made the scholarly gathering “international,” I had to be driven to and from the closest open county every day in order not to spend more than 24 hours in a “closed to foreigners” county (the same went for my village visits too).

Most of the other participants at the conference were men from various branches of academia—history of writing, anthropology, sociology, archaeology, and so forth—and what seemed to interest them most was the possibility that nüshu was a very ancient and secret language. Some compared it with the characters on the ancient oracle bones, the earliest known example of Chinese writing, dating from the 2nd millennium B.C., and would argue with anybody who countered there was no proof for that. This gave me a taste of what was eventually to come: the story that took hold was that nüshu was a secret language that for centuries women used to communicate their sorrow to other women.

Being quite young, I couldn’t contain my irritation at this: If something is largely known just by its users, it doesn’t follow that it has been kept secret. I walked around the village asking the children of the nüshu-writing women if they knew of their mothers’ “secret,” and they all laughed and told me there was no secret—they had seen their moms write it since they were toddlers. It was just a useless pastime, they said, and that’s why nobody spoke about it outside of Jiangyong.

And when nüshu was read aloud, everybody could understand the meaning—it didn’t transcribe a female-only language but the local one. I sat with some of the old ladies who had studied the script together, reunited after widowhood, laughing with each other while reading old books that related jokes and personal adventures from their younger days. If at times they had written also of the trials of life—such as we all experience—it was only one thread in the larger tapestry of nüshu.

I studied nüshu and the peculiarities of the region into which it was born for a few years—the ethnic complexity of the area, for example, home to the majority Han group, but also populated by Yao, Zhuang and Miao people, and how the women of Jiangyong had managed to develop something so strong and unique. My favorite line of inquiry was about textiles, in particular among the Yao, where women would embroider and weave symbols—distinct from nüshu, however—into clothing, blankets, and so forth. The symbols, intelligible to other women, showed what had been happening in their lives. Men too could have interpreted these textiles if they so wished—no secrets there either—but in general they were not interested.

Yet, these nuances are not what people have been interested in since the existence of nüshu became known outside of Jiangyong. After that first conference, more articles were written and more visitors arrived, and China continued to open up to foreign travelers. As nüshu emerged from its native environment, it fascinated many who encountered it, including artists and writers. But it did so with that old twist. Most interpretations and headlines have been about a “secret language” that women used, preferably to communicate their pain.

Nüshu beyond Jiangyong

The Chinese composer Tan Dun, for example, wrote a symphony that premiered in Japan in 2013, called “Secret Songs of Women.” In 2004, when the Jiangyong writer Yang Huanyi passed away, the few obituaries of her that I read talked of a mysterious code. In 2005 the Californian writer Lisa See wrote a novel, Snow Flower and the Secret Fan, then made into a film, that revisited the same ideas.

I stopped following the progress of nüshu into wider culture. The world wanted a secret language used by oppressed women to communicate pain, and it seemed there was no fighting it. I felt people were reading into it what they wanted, regardless of what it meant, at times for personal profit. Isn’t this the standard definition of cultural appropriation?

Its traces beyond Jiangyong came as the script slowly fell entirely out of usage in the past 25 years or so, as the last women who had grown up learning and using it passed away, and new generations of girls were schooled in the standard national system. That it existed at all is extraordinary, given how strong the prestige of the Chinese script has been over the centuries.

As nüshu’s seduction slowly spread, the authorities in Jiangyong tried to leverage it for tourism. The area is still poor, and the county as been marketing itself as the land of nüshu and pomelos (link in Chinese), hoping to attract visitors.

Occasionally, nüshu pops up on the internet in unexpected ways. There is a US website of self-styled “Nüshu Sisters” with new-age and self-help vibes that also sells t-shirts and totes with nüshu words and stickers with inspirational quotes (“Be the Best You,” “Deeply Love and Appreciate Yourself”). More seriously, last year, the Unicode Consortium, an organization that creates encoding standards for languages and scripts so they can be used across computer platforms and programs, turned its attention to nüshu.

These uses may be far removed from the women of Jiangyong—but clearly what they created has been able to speak to people in far-flung places. Slowly, I started to think, perhaps trying to box their culture into one single definition might be a disservice to them. If nüshu, in this unforeseen way, has been extending its journey of inspiration and communication, should anyone really be its gatekeeper?

Last year, as I was traveling through Mexico, I fleetingly bumped into nüshu again—and unexpectedly made my peace with its journey. A Mexican woman I met told me that she has a nüshu sentence tattooed on her back, which she showed me before knowing it had been my topic of academic research for years. I didn’t ask her what it meant. But I saw the respect and joy with which she carried it, and I realized that the script has made its own way into the world, and speaks to people in an evolving language, full of meanings that nobody can attempt to control.