The astounding thing about the global abortion debate is not that some people have deeply held views about what a pregnancy is and when a human existence begins. After all, both of these questions are closely related to that most ubiquitous of philosophical questions: what is the meaning of life? The astounding thing is that policy-makers continue to ignore carefully amassed information about the actual outcome of programmes and laws related to sexuality and reproduction.

In that context, one could only wish that the latest figures on induced abortion rates and unsafe abortion came as more of a surprise. The analysis, carried out by the US-based Guttmacher Institute and published in the Lancet, has two main conclusions: first, when governments fail to provide contraception for those who want it, abortion figures stay the same; and second, where abortion is illegal the procedure is predominantly unsafe. The foreseeable consequence – continued high levels of maternal mortality – also plays out in the data.

None of this is new or surprising, and we have, as one health advocate pointedly noted, known it for decades. The aggregate data, however, hides additional details the discerning policy-maker should take into account.

First, overall abortion and fertility rates present the consolidated result of millions of very personal decisions.

It is not an accident that abortion rates are higher and procedures more unsafe in poorer countries generally, and for poorer women everywhere. Because even though decisions about abortion are personal, the context in which they are made is not. In this sense, the frequency with which women and girls need abortions and the conditions in which they feel compelled to access the procedure is in many cases an expression of exclusion, stigma and discrimination.

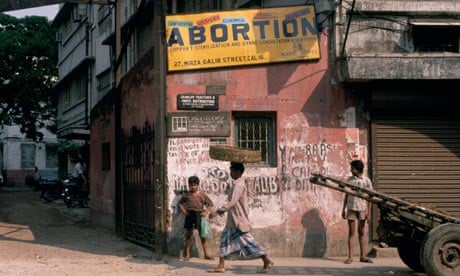

This is most clearly illustrated by the seeming anomalies in the Guttmacher study. Take a country like India. Abortion is generally legal, and modern contraceptive methods are, in theory, available. Even so, the study found that two thirds of the 6.5m induced abortions that occurred annually in India were unsafe. The reason for this is the combination of available health infrastructure, poverty, moral condemnation of sex outside marriage and severe gender inequities in the labour market. This is the context in which the women and girls make their decisions. Those who are most likely to need an abortion – young or unmarried women, those pursuing education or those engaged in subsistence farming – either cannot afford a legal procedure or fear the stigma attached to going to a recognised clinic for care. As a result, they end up having unsafe abortions, not because the government doesn't allow legal care, but because it does not enable women to effectively access it.

Second, the 70,000 women who die annually as a result of unsafe abortion didn't just die because abortion was illegal in the country they live in. They died because their lives were seen as dispensable by those in charge. Maternal mortality caused by unsafe abortion is, in fact, entirely resource-specific. This is the very reason policy-makers can and do continue to ignore facts: the only women who die as a result of restrictive abortion laws are poor. Case in point: Mississippi, the US state with the highest poverty rate, also has incredibly restrictive abortion access and – not surprisingly – soaring levels of maternal mortality.

Finally, the study hides massive levels of complacency (or resignation), even among those of us who care. How is it that we don't ask for more informed positions from our policy-makers? Regardless of whether we identify as pro-choice or pro-life, or neither, we should all require some sort of plausible explanation for why the suggested solutions actually would generate the change we want. In this sense, if a key goal is lowering the number of abortions, we should not accept policies that police women's sexuality based on particular conceptions of morality.

In fact, we should accept nothing less than what the data for decades has shown to be effective: a policy package of comprehensive sexual and reproductive healthcare, including support for parenting, gender equality and poverty reduction.