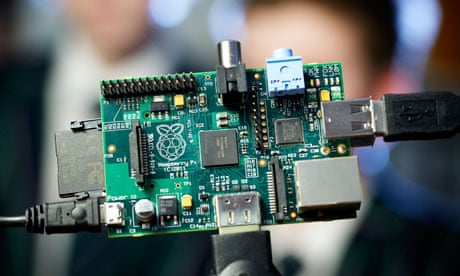

Two interesting things happened last week and neither had anything to do with social networking or privacy. First, a web server fell over. Nothing new in that, you say; happens all the time. Yes, but this wasn't any old web server: it was the machine that hosts the Raspberry Pi site. It was overwhelmed because, on Wednesday at 6am, the project released its first product – a credit card-sized computer board that costs £22 and which, when plugged into a TV and a keyboard, turns into a fully programmable computer running the Linux operating system. "Guys – can you please stop hitting F5 on our website quite so often?" pleaded the webmaster at one stage. "You're bringing the server to its knees." The swamping of the site by people desperate for news indicated that something was up.

The second thing that happened confirmed this hunch. The first batch of 10,000 units to be made available through major device resellers such as RS sold out within minutes of going on sale on Wednesday morning. This was the geeky equivalent of the Glastonbury ticket scrum.

So something is indeed up. The Raspberry Pi project – a philanthropic effort to create the contemporary equivalent of the BBC Micro of yesteryear – has graduated from idealistic vapourware dreamed up in Cambridge to a finished, deliverable product manufactured in China. (In a nice touch, the Pi device comes in two flavours, Model A and Model B, just like the BBC machine, which was also designed in Cambridge.) Over the next few months, we'll see container-loads of the little computer boards delivered to these shores. The time has come, therefore, to start thinking about how this astonishing breakthrough can be exploited in our schools.

Here are a few suggestions.

First, we need to jettison some baggage from the past. In particular, we have to accept that ICT has become a toxic brand in the context of British secondary schools. However well-intentioned the thinking behind the ICT component of the national curriculum was, the sad fact is that it has become discredited and obsolete. As a result, educational thinking about the importance of computing and information technology in this country has been stunted for well over a decade. We've taken a technology that can provide "power steering for the mind" (as a noted metaphor puts it) and turned it into lesson for driving Microsoft Word.

Second, we need to persuade Michael Gove and his colleagues that the subject that should be taught to all children is not ICT but something called computer science. The idea that there's a major body of knowledge in this field – complete with a stable and intellectually rigorous conceptual framework that is independent of today's or yesterday's gadgetry – is probably unfamiliar to residents of Whitehall, who think ICT is trivial because it's always becoming obsolete.

Learning about computer science involves learning to program – to write computer code , because this is the means by which computational thinking is expressed. We wouldn't dream of teaching pupils about German culture without expecting them to speak German. The same holds for computer science.

Third, those of us who are evangelists for this stuff need to recognise that the arguments in favour of it are not just the pragmatic or economic ones that have been advanced so far – for example the line that we need schools to teach computer science to halt the decline in undergraduates studying the subject, or that parts of the UK economy – eg the games industry – need skilled programmers (though it does).

There are actually far more important reasons why our children should emerge from school with a deeper understanding of information technology and computational thinking than is the case at present. They are to do with citizenship and democracy.

The world our children will inherit is one that will be shaped and controlled not just by physical realities, such as climate change, but by computer software. And the choice they will face is the one expressed in a recent, sobering book by Douglas Rushkoff, entitled Program or Be Programmed. "Like the participants of media revolutions before our own," he writes, "we have embraced the new technologies and literacies of our age without actually learning how they work and work on us. And so we, too, remain one step behind the capability actually being offered to us. Only an elite – sometimes a new elite, but an elite none the less – gains the ability to fully exploit the new medium on offer. The rest learn to be satisfied with gaining the ability offered by the last new medium."

Is that what we want for our children? The answer has to be no, which is why we need to teach them computer science. Raspberry Pi offers us the chance to do just that. Will we have the courage – and the vision – to take it?

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion