Bathing, by Duncan Grant, 1911. Photograph © Tate (CC-BY-NC-ND 3.0).

Being gay in Britain in the 1950s was not easy. This was an uptight, grey little decade, with the country victorious from the Second World War and paying the price, with rationing lasting until 1954 and National Service not being fully phased out until 1963. The war had played havoc with personal relationships. Families had been split up, children were sent off to the countryside and those who were called up were posted all over the place, forced into close contact with strangers. Around 450,900 British people were killed as a result of the Second World War, many of them while serving in the military, but there were around 67,000 deaths as a result of airborne attacks on British towns and cities, including two of my great-uncles who were killed as children when a bomb was dropped on the house they had taken cover in during an air raid. Britain was a nation in grief.

Thinking that this might be your last few hours alive, during night after night of air raids, has a way of making you live for the moment. And a lot of clandestine sex happened, in lodging houses, in the Blackout, in army bunks, in the back rows of cinemas, in public loos, in parks, in alleys, and, well, people often turned a blind eye because there was really too much else going on to worry about. Even in the armed forces, homosexuality was mostly tolerated, with soldier and gay rights activist Dudley Cave noting that “With Britain seriously threatened by the Nazis the forces weren’t fussy about who they accepted.” And then the war ended. There was a reassertion of family values and a baby boom, as new couples set about making families. Wartime indiscretions needed to be put aside, and homosexuality, which had fallen off the moral agenda during the war, was suddenly back on it. A survey of British values in 1949 found that most people were horrified and disgusted by it.

After the war, the political landscape across the world was somewhat different from how it had been before. From around 1947 there was a state of political tension referred to as the Cold War between the Eastern Bloc (comprising the Soviet Union and various satellite states) and the Western Bloc (chiefly the U.S., NATO countries, and other allies). In 1951 British-born Guy Burgess fled to Moscow, realizing that he was about to be unmasked as a Soviet spy. Burgess was Cambridge-educated and had worked for MI6 and the Foreign Office. He was also gay, as was Anthony Blunt, another member of the spy network referred to as the Cambridge Five. With few (if any) positive depictions of gay people in public life at the time, Burgess became a kind of stand-in for homosexuals—not only were they criminals but they were also likely to hold all sorts of sympathies for those who wanted to threaten our way of life, and that included becoming a traitorous communist spy for Russia.

And there was a dolly new queen in town. Her name was Elizabeth, and her coronation was about to take place in 1953. The eyes of the world were on London, and some of the other queens around at the time noted that the authorities seemed especially keen on imposing a kind of cleanup campaign on the country. Drag queen Ron Storme observed that during this time drag shows were banned and that if you went out in drag, even if you were just sitting in a car minding your business, the police would make you get out, then arrest you for soliciting. It’s certainly the case that the number of reported indictable “homosexual offenses” was going up and up—178 such convictions were reported in 1921, but by 1963 it was 2,437, more than double the number for heterosexually related offenses that year. The police had long known that convicting gay people was easy. They usually didn’t appeal or complain at their treatment for fear of attracting publicity, so for police who wanted to make a slew of easy arrests and convince others that they were cleaning up Britain’s morals, staking out the local public park or loo was a doddle.

No gay man was safe during this period, with stories of persecution appearing like a sinister combination of George Orwell and Franz Kafka. In January 1952 Alan Turing, the man who had cracked Germany’s Enigma machine codes in the Second World War, making a significant contribution to ending the war and saving countless lives in the process, reported a burglary at his home after one of his partners, nineteen-year-old Arnold Murray, told him that the intruder was an acquaintance of his. Turing acknowledged his relationship with Murray to the police, who then decided to prosecute Turing instead. His security clearance was removed, and he was banned from working with Government Communications Headquarters or entering the U.S. On his conviction he was given a choice between prison or chemical castration with probation. He chose the latter, which meant receiving injections of synthetic estrogen. Turing grew breasts and became impotent. He was found dead on June 8, 1954, with the postmortem establishing the cause as cyanide poisoning. There is speculation about whether this was an accident owing to him storing laboratory chemicals at home or suicide. There was a half-eaten apple beside Turing’s bed, which many believe he had dosed with the poison—his biographers have suggested he was enacting part of the story of Snow White and the Seven Dwarves. But whatever the cause, there is no changing the facts about his disgraceful treatment by the British authorities. The government did not apologize until 2009, and he was not pardoned for “gross indecency” until 2013.

Turing’s is a high-profile case, as Oscar Wilde’s was a half century earlier. This should not detract from the thousands of gay people who were convicted for their sexuality during those decades, turned into criminals for loving or fancying someone, another adult, consensually. And beyond those thousands are countless others who were not convicted due to either good luck or constant vigilance, those who lived secret gay lives, worrying that today was going to be the day they would be caught. And beyond them are more still who decided that the risk was too much, that they would repress their feelings and be celibate or get married for the sake of appearances. How cruel to feel you had to live a lie and involve others in it too—the disappointing honeymoon, the decades of sexual frustration and fear of having your secret exposed.

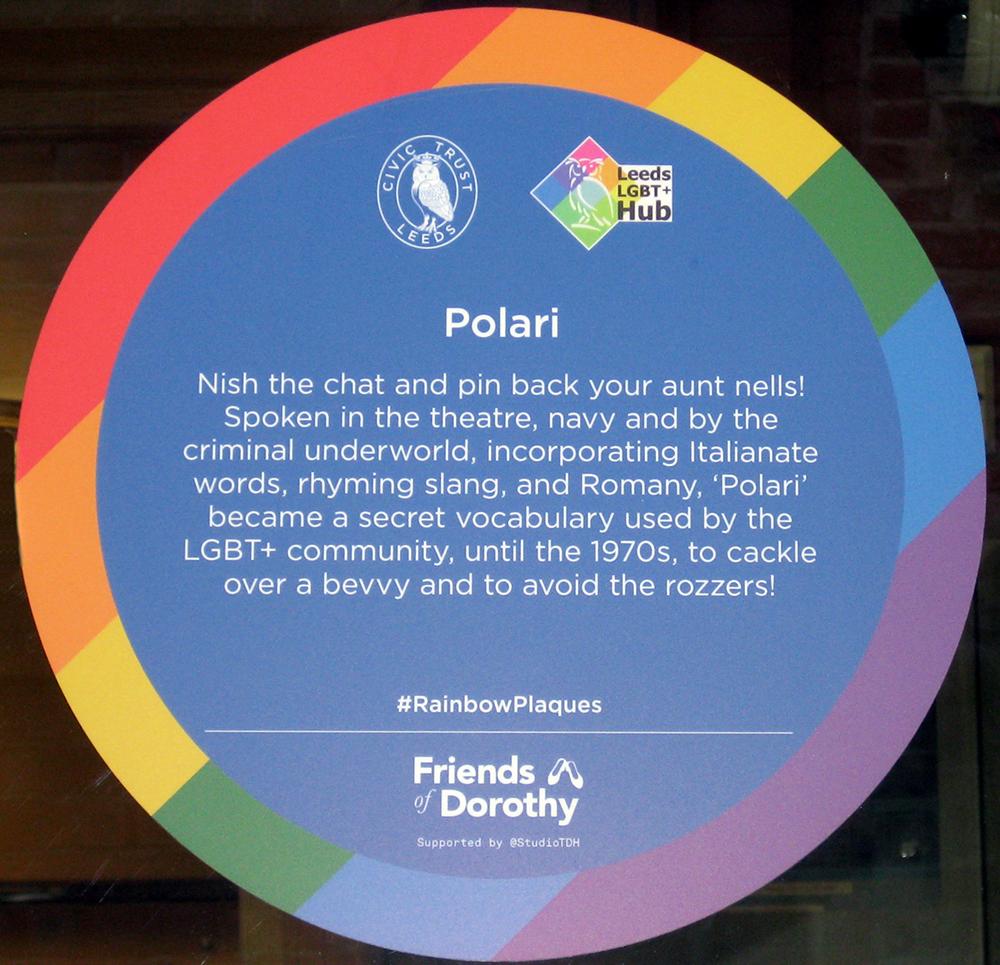

And so it was in this climate of state oppression that Polari came into its own. Polari was a secret, mainly spoken form of language in Britain which occurred in private conversations among people who were not part of a social elite and has roots in forms of language that were around long before the invention of recording devices, so we often have to rely on secondary sources, hearsay, theories, and educated guesses. Apart from a couple of notable exceptions, it was not viewed as especially interesting or worth researching. The few attempts to provide written accounts of the language or transcriptions of it illustrate the lack of standardization. This was very much a language variety that was subject to change and developed on the fly by groups of people who belonged to multiple communities, as opposed to it existing within a single community where everyone knew everyone else. Even by the time we get to the early twentieth century, the notion of a single gay community who all knew the same Polari words and used them in the same way is mythical.

One of my interviewees, John, described how Polari was used “specifically as a hidden language”: “You would say ‘Vada the cartes on the omee’ because nine out of ten times [heterosexuals] wouldn’t understand what the hell you were talking about.” And Polari was especially useful for conducting conversations in public spaces, especially on public transport. DJ Jo Purvis described how she “could sit on a Tube train or a bus and talk about the person opposite using this Polari which no one could understand except theatrical people.”

There was no such thing as a safe space in 1950s Britain, but Polari helped to create a kind of symbolic safe space for gay people of the time by allowing them to talk in ways which otherwise would have revealed their sexuality to anyone who was listening.

It is simplistic, though, to think that at the time people were consciously aware of how speaking Polari was helping them to cope with the oppressive times; this was perhaps more likely to come in hindsight. Drag queen Bette Bourne, interviewed in 2014, recalls:

You never thought, “Oh God I’m so oppressed I can’t speak about myself,” you just did it. You just slipped into [Polari] without even thinking really…It wasn’t like this great terrible thing hanging over me, which eventually…we realized yes it was a fucking drag, the whole thing was terrible and awful and made people very secretive and suspicious and wary, very wary, but once you got that together it was fine. You had the equipment…Those things are forced upon you. They’re not just invented as a camp joke. They’re practical.

Polari could also be employed as a kind of “secret handshake,” enabling recognition of a shared sexuality between two strangers—a careful way of coming out of the closet, or at least of opening the closet door a crack. One of my interviewees described it as a “non-giveaway that you were gay,” while Dudley Cave described Polari words as “secret passwords. You could identify with other gay people if you thought they might be—you could drop a word in like ‘camping about’ or ‘I’m going camping, but I’m taking my tent.’ ” Such code words would be likely to result in a nonplussed reaction if the hearer wasn’t gay and so were a reasonably safe way of revealing one’s identity without being overly explicit, and could be shrugged off as a simple misunderstanding if someone had the wrong quarry.

Camp names had a secrecy function, too. In an interview in Gay Times, David, who was fifty-six in 2002, describes his early experiences on the gay scene in the 1960s, watching Mrs. Shufflewick perform at the Black Cap and modifying his language so his parents wouldn’t know that he was gay:

A guy I met at the Black Cap was a nurse, so I could say to my parents, “Oh I’ve met a nurse called Susan.” You just got used to it. Madge was a particularly popular name.

The need for secrecy helps to explain the set of Polari words that function as euphemisms, being taken from English words but having altered meanings. For example, one of the men interviewed by Jeffrey Weeks and Kevin Porter for Between the Acts: Lives of Homosexual Men, 1885-1967 described how another word, so, was used to mean gay, whereas the phrase “to be had” was put into abbreviated form, again making it difficult for outsiders to understand its meaning:

We were “so.” Have you heard that word? We were so. Is he so? Oh yes. Oh he’s so so, and tbh (to be had) was a very famous expression. The sentence would go simply like this, well he’s not really “so” but he’s tbh. And you would know exactly.

The journalist and author Peter Burton describes a fascinating use of Polari which was more about confrontation than conformity. Burton was born in 1945, so he is likely to have been a Polari user in the 1960s and ’70s, when the social climate was starting to thaw a little and flamboyant attire was seen as fashionable on young men. Burton writes: “We flaunted our sexuality. We were pleased to be different. We were proud and secretly longed to broadcast our difference to the world: when we were in a crowd.” He acknowledges that in hindsight it must have been obvious to everyone what he and his friends were talking about when they used Polari.

In such cases, Polari with its strange words and exotic intonational patterns would have probably helped to identify some speakers as gay—being just one symbol among numerous others of their sexual difference. Burton’s use of Polari, then, is suggestive of a bolder queen—one who clocks the dirty looks and laughs from straight strangers and responds with a mouthful of insulting Polari—the language could be used to “confound and confuse,” in Burton’s words. The target of the verbal abuse would know they were being insulted but unable to respond because they couldn’t understand the language. There is something particularly frustrating about being insulted in a language that you don’t understand—you are instantly wrong-footed, and it can be difficult to respond in kind. In such cases, Polari assumes an occult, almost magical quality, taking on the form of a withering spell.

Reprinted with permission from Fabulosa! The Story of Polari, Britain’s Secret Gay Language by Paul Baker, published by Reaktion Books Ltd. Copyright © 2019 by Paul Baker. All rights reserved.