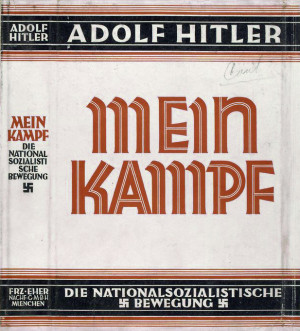

On May 8, 1945, the Allied powers declared victory in Europe, putting an end to the Nazi regime. There was much to be done, and figuring out what to do with Mein Kampf (“My Struggle”), Adolf Hitler’s fictionalized autobiography, was prominently on the list. In the years leading up to and through the war, one in five Germans had read the book. Clearly, there was no place for it in postwar Germany.

After the war, many copies were discarded and, for a time, the book was banned. But, not wanting to be seen on par with the book-burning Third Reich, the outright ban on Mein Kampf was only temporary. Ultimately, the issue became a question of how to limit access to the book without outlawing it.

The rights to Mein Kampf were given to the Bavarian government, which decided not to publish any new German editions, and worked to ensure the existing copies held by libraries were only used for scholarship, not politics. Fortunately, Germany had a centuries-old system in place for just such a nuanced approach: the Giftschrank.

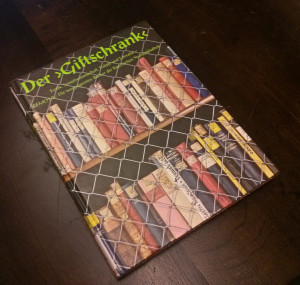

The word, a combination of “poison” and “cabinet,” has a variety of meanings in different contexts. At its most literal, a Giftschrank is a space for storing controlled substances in places like pharmacies. Colloquially, it can refer to spaces reserved for all kinds of hidden and forbidden objects, ideas or stories.

Deep in the heart of the Bavarian State Library in Munich, the Giftschrank was a box (and later, a room) for storing books that were seen as potentially hazardous. Over the years, such “poison cabinets” or “poison rooms” in this and other German libraries would fill up, get emptied, fill up again—the contents of the Giftschrank speaking volumes about what German society considered dangerous at any given moment.

In the 1580s, when Bavaria was a kingdom inside the Holy Roman Empire, the state library was concerned about works considered heretical by the church, like the writings of Martin Luther and Galileo. The monarchy did not want to destroy its own collection of these volumes, and instead opted to hold onto books in order to better understand the arguments of their enemies. The Duke of Bavaria put 500-some contentious volumes in a locked box, calling it the Giftschrank.

Over time, the Catholic Church started to lose its grip over Europe. By the 1800s, German libraries were less concerned with protecting people from the Protestant writings of Martin Luther, and more concerned with issues of sexuality. Upon the death of an erotica collector, the King of Bavaria came into possession of a private collection of adult books. Unwilling to throw these controversial books out, or to make them readily available, librarians found a home for Franz von Krenner’s erotica collection in the Giftschrank.

More time passed. Germany fought (and lost) World War One, and from the rubble of that defeat grew a liberal counterculture. Berliners passed late hours at cabarets. Dadaists proclaimed that art was dead. In the middle of this period of experimentation and exploration, physician Magnus Hirschfeld published journals and books arguing for the acceptance of homosexuality and transgenderism as normal, writing:

The woman who needs to be liberated most is the woman in every man, and the man who needs to be liberated most is the man in every woman

Hirschfeld was also a promoter of sex education, contraception, female emancipation and other controversial topics. (This may sound familiar if you watched the second season of Transparent, which featured a secondary plot line about Hirschfeld).

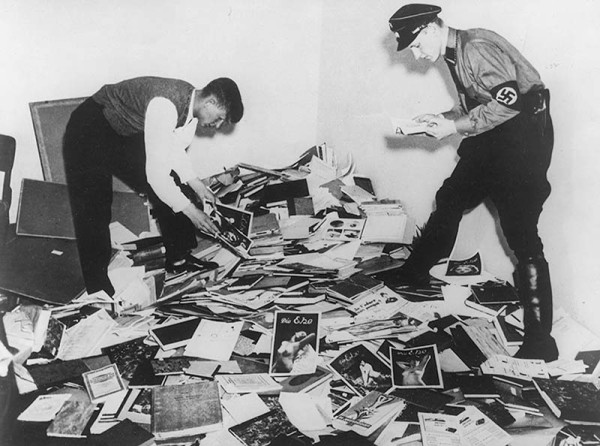

As the Nazi Party rose to power, Hirschfeld’s Institute for Sexual Sciences became a target.

In May of 1933, the German Student Union, a group affiliated with the Nazis, raided the institute. They threw many of his books onto the street, and burned them. This was four days before Nazis all across Germany start burning books by Jewish authors in public rallies. What was not destroyed went (of course) into the Giftschrank.

Twelve years later, in 1945, the Nazis had lost the war. And now their own literature, including Mein Kampf, was put in the Giftschrank. This was seen as a crucial step in shaping a fresh postwar society, or rather: a pair of new societies on either side of the Iron Curtain.

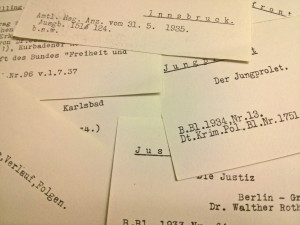

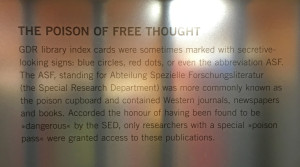

Both East and West Germany would come to have their own government, culture and institutions, including library systems. The contents of their respective Giftschränke spoke to the divergence of this split nation. Each side stowed the writings of Nazi leaders like Hitler, Joseph Goebbels and Alfred Rosenberg, but as western Giftschränke began to empty of other contents, those in the eastern GDR started to fill up with everything from political writings to foreign poetry.

At the University of Leipzig, the Giftschrank lived behind an iron bunker door, available for access only by academics and students granted special permission. And while some sought to gain admission in order to read subversive tracts or political news, many simply wanted a window into the West, to take a peep at pop culture, music or fashion magazines.

In the years following the reunification of East and West Germany, and through the dawn of the digital age, the Giftschränke have become increasingly empty. Some volumes, like Mein Kampf, still live in a sort of “virtual Giftschrank,” thanks to library systems blocking direct access. Young people need parental permission, and other readers must give legitimate reasons for wanting to read the book. These days, of course, copies can also be found in antique bookstores or on the internet. Libraries aside, it has simply become more accessible.

On January 1st, 2016, the copyright for Mein Kampf expired, putting the book in the public domain.

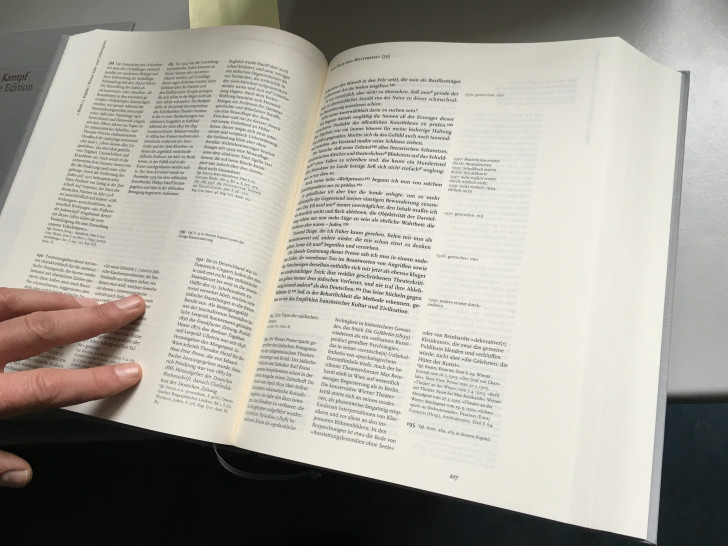

The Institute for Contemporary History in Munich has just published a new, critical edition of the book.This edition is big, heavy, and expensive; its two volumes feature 1,500 pages of footnotes and commentary meant to disprove and contextualize all of Hitler’s claims.

Looking inside, there is no way to mistake this for anything but an object of scholarly study, and readers must work through layers of critique. It is almost as if the publishers have wrapped a kind of portable Giftschrank around the new edition of Mein Kampf so that it can be more safely sent out into the world.

Comments (12)

Share

See a plaque where the Berlin Wall used to be, and Sam Greenspan’s and Helen Zaltzman’s feet, at http://readtheplaque.com/plaque/berlin-wall!

Fascinating story. And I so love that I didn’t see that perfect poetic ending coming. A critical edition of Mein Kampf as Giftschrank! Great job!

At the beginning of the episode, Roman refers to Mein Kampf as a “fictionalized autobiography”. Why does he refer to it as fictionalized? I’m curious what parts were invented. Do you have a reference I can read?

Sam here: I’ve only read parts of part of it, but Sven Felix Kellerhoff wanted me to stress that Mein Kampf is less an autobiography than it is a Bildungsroman (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bildungsroman), and a heavily fictionalized one at that. The story of the book itself is also quite fascinating, but unfortunately couldn’t fit in this story about the Giftschrank.

If you read German, pick up a copy of Kellerhoff’s just-released “Mein Kampf: Die Karriere eines Deutschen Buches” (Mein Kampf: The Career of a German Book): https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/26857457-mein-kampf—die-karriere-eines-deutschen-buches

The English edition is coming out later this year, I believe.

This has been happening ever since the site upgrade. Why does streaming the episode from the player automatically stop playback at 1 minute? In the case of this episode, it also stops plaback at around 3:16 in and won’t play any further.

I just tried playing it on the Stitcher webapp as well and encountered the same problem. This is the only podcast that I listen to where I’ve experienced this, the others seem to work fine.

FYI, Mein Kampf is widely available in India, at least in bookstands in most every major train station I’ve seen in the subcontinent, which is quite a few. Always on the go at the time, I’ve never gotten around to asking why.

I found this episode very interesting. Thank you. One thing had me halt and raise my eyebrows. Why don’t they let goths read Mein Kampf in the library? I am a goth from Bavaria and I read tons. I am very interested in history. Why should the way I dress affect what I am allowed to read? This whole subculture does not have a political direction. Yes, there are military gothic types, but so are… “hippie” goth types.

I would like to know the reason for this. I only have a guess: maybe the wide spread heavy boots seem military? The SS had black uniforms with skulls. But usually a skull on black lets me think of (romanticized) pirates first.

You could try dressing incognito for a day perhaps? There’s no rule that you have to wear the uniform every day, you could wear a nongoth persona for a day to read the book.

The Stephen Kellner link seems to be broken. Is there a English version of his The Giftschrank book?

Is there a RSS feed, twitter feed, blog, or something that would have updates about the progress of Sven Felix Kellerhoff’s forthcoming English edition?

Has the IfZ published an english edition of the Kritische version of Mein Kampf yet? Any feed for updates about that?

Thanks.

Hello,

why is there a video about the east germans fleeing the gdr? This is somewhat unrelated to the topic….

We had that in Quebec too! “mettre à l’index”. Finally a good use for it!

I wish I could post a picture here. I work at a recycling depot and I just found a child’s craft project with the words “this safe contains a relly inapropiate Book keep out!” I instantly thought of the giftschrank episode and the idea that a small child was playing make believe giftschrank!