TL;DR It’s hard to solve problems that are open, experts won’t help, filter bubbles, why does it matter if you are angry reading all this, double loop learning Clean Feedback and anti-fragility.

TL;DR It’s hard to solve problems that are open, experts won’t help, filter bubbles, why does it matter if you are angry reading all this, double loop learning Clean Feedback and anti-fragility.

Thanks to Chris Cupit, Tomasz Glazer and Richard Harris for the discussions around this topic, and to Andrew J. Baker for feedback and pointers.

What are Mikhail Bongards problems, and why should I even care?

Quick Overview

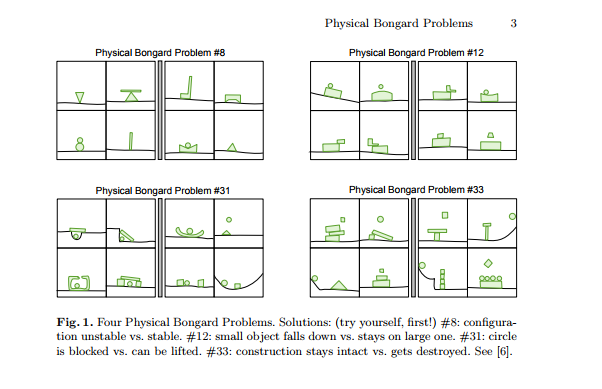

Mikhail Bongard invented a type of puzzle called a Bongard Problem. These problems are interesting because you get to see all the answers. You need to work out the question. Bongard problems have two sets of six images. The solution to the problem is the explanation of the difference between the two.

These inductive reasoning problems help us understand how we think in the real world. The book Goedel Escher Bach provides a methodology for solving Bongard problems, with a slant towards using Artifical Intelligence. At first the AI community thought these problems would a straightforward path to implementing AI. They’re not. And they’re much simpler than the other two examples of real-world Bongard Problems I’ll use.

This post discusses how these problems can be seen in the real world, and how they are connected to learning, and our approach to life.

How to Solve Bongard Problems

An example of Hofstadter’s methodology from Goedel Esher Bach is below. Note that this methodology is wrong for the problem that is being solved. I’ll call Goedel Esher Bach GEB from now on.

The method involves having a vocabulary for the domain, and an understanding what Gregory Bateson calls “the difference that makes a difference”.

Ninety-Nine Problems

Mikhail Bongards book Pattern Matching has one hundred problems. Solving these we can keep adding to the “difference that makes a difference”. We can build a list of all the heuristics we need, becoming an expert in this set of Bongard Problems.

When this list exists we have a vocabulary that gives two different approaches available to someone new to the problems.

Approach One, an open problem

This first approach is when you don’t know what the potential rules are. For example, you don’t if there is a rule that “If the pictures were physical and upright, their center of gravity would make them unstable”.

If you don’t know what the potential rules are, the potential number of solutions is unlimited, and you’re going to invent some potential solutions that are not used. So you could make new never been seen Bongard problems from these guesses.

How may these problems be seen by an expert in the original 100 problems?

Approach Two, you know the rules

The second approach is solving the same set of problems, but you have the language of all the solutions. This doesn’t make the problems trivial, but it’s a different type of problem. You have expert knowledge in the domain, and you’re doing pattern matching. You can combine patterns, but you might not be looking for new ones.

The difference that makes a difference

I’ll use a distinction between knowing all the solutions in advance, and not know them in the following three examples. I’ll then add the extra case where you think you know all the answers, but there may be other answers. Or put another way, you have a consistent explanation for how the world around your problem works.

I’ll use three examples

- Playing the tabletop game Zendo

- Understanding Organizational Strategy

- Investigating unlawful credit card harvesting from your website

Example 1: Zendo

Zendo is a board game based on Bongard problems, using inductive logic. It used 3 shapes in three colours, and the idea is that a particular configuration of coloured shapes is given on a card, and players need to create structures that follow the rule on the card, and then win by correctly guessing the rule. So the Bongard problem is a configuration of shapes that is correct, and one that is wrong. You get to offer new configurations and see if they match the pattern that is the difference that matters between the two shapes.

Example 2: Organizational Strategy

Consider the case when a company makes some strategic actions. What is their new strategy? How has it changed? There will be some visible action, so one half of your Bongard Problem is the organization running one strategy, the other is the organization with the current strategy.

If you can figure out their change of strategy you can react to it with your own. If you fail to understand their strategy or carry on regardless you may go out of business.

Examples 3: Computer Crime

In this article, David Gilbertson describes how he’s hidden some code to harvest credit card details in a website that the reader may either own or use. Many website use frameworks that have a load of code imported into the pages. The data theft is viable.

In this example one half of the Bongard problem is your unhacked site, the other is a potentially hacked version. The Bongard problem is to prove that there is a difference. i.e. You’ve been hacked.

Example 1: What happens when I play Zendo with the kids

When I first played Zendo with the family I chose not to look at the cards describing the patterns that we could look for, and I didn’t show the family. We started from scratch and didn’t have a vocabulary.

It was very frustrating to play, and we made some crazy guesses.

The vocabulary on the cards includes orientation, colour, number, and layout. Doorstop, cheesecake, and tower were in the solution vocabulary.

We could now attempt the easy questions. Having a vocabulary is a required part of solving the problem in GEB.

When my son decided to choose a medium difficulty question we started with the usual guesses, but when we didn’t seem to be getting close we started to get agitated. We didn’t know the rules of the problem domain. More precisely, we didn’t have the vocabulary for the potential patterns. The temptation to ask for a clue or to give up was huge, because this was a game, and games are supposed to be fun. We did, however, have loads of crazy guesses that were not on the game cards. Failure is frustrating, especially if you are not expecting it.

Zendo with work colleagues

I then played the game with the Systems Thinking group where I work. I didn’t give my colleagues any information about the vocabulary or patterns. They were quickly able to create new patterns that matched the rule but couldn’t describe the exact rule that was written on the card I was using.

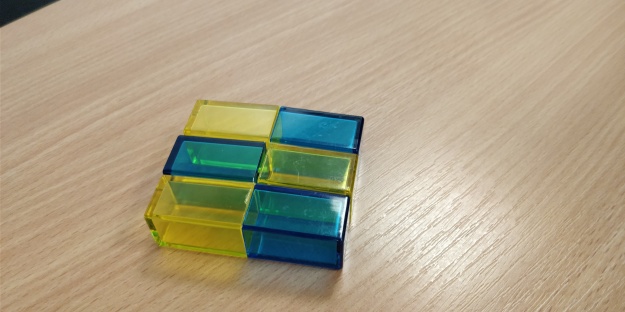

The problem they had was there were two potential orientations for one of the pieces but without knowing this it was not a difference they noticed. As the photo above shows, the wedge shape can be in the ‘cheesecake’ or ‘doorstop’ orientation. If we’d read the instructions this would have been obvious. If we don’t have a name for something we have a hard time spotting it. Even if it is the difference that makes a difference.

After this game, without looking at the potential Bongard problems Tomasz helpfully created a problem that wasn’t on any of the cards. He put together some clear blue and yellow pieces. His pattern rule was “structures that can look green”. He’d created a new type of problem, unconstrained by rules. (EDIT : Tomasz was unconstrained by ‘being an expert’)

How might an experienced player who is familiar with all the vocabulary and patterns on the cards go about solving this problem?

Example Two: Strategy

In business, our competitors’ strategies are unknown to us. They may be easy to spot, or they may confound us.(explained in Patterns of Strategy). There are examples of strategies on the web, that suggest a more complete list exists (here is a great list of Strategic Gameplay from Simon Wardley).

I’m not familiar with all the strategies listed above, but I can recognize a few of them in the wild.

We are unlikely to get a clue from our competitors, but we can ‘give up’ and have a strategy of just carrying on what we’re doing, head in the sand. We think our strategy is fine.

We know there are more strategic possibilities out there. It’s not clear to me if there is a definitive list of strategies available that is considered complete.

Is a new strategy possible? I think it should be. Does knowing all previous strategies help? I’m not sure. Is it possible to think up new strategies that are not covered by known ones? I don’t know enough to know. Is strategy an open or closed problem?

Example Three: Fighting Computer Crime

After describing how he would insert code to harvest credit card details on websites, David Gilbertson goes through the ways that the reader, who is likely to be knowledgeable on computer security, would use to discover the exploit code. These ways are the patterns and vocabulary to solve the problem.

David then systematically shows how each of our ways of finding the code is flawed and sows enough doubt that we may not find his code.

We thought we had a full set of tools, but it’s clear we don’t. We can’t choose whether to learn our knowledge is flawed, it’s forced upon us. It’s a painful read, and it probably makes people angry enough to prove him wrong!

What’s just happened?

Thanks to Andrew J Barker (@ajbkr) from Tech Nottingham Slack for pointing me in this direction, but any mistakes here are mine.

What is happening when we face an open inductive logic puzzle and we don’t know the full range of answers? I’d suggest that we’re not just learning the answer, but we are double loop learning (see wikipedia, by Chris Aygryis). Our current problem-solving skills are not enough. We’re recognizing this and by getting some new tools.

Double loop learning is not just realizing there is something to learn, like a new computer language, or musical instrument, and learning it. Double loop learning is finding that your old tools don’t work on the problem you’re facing, maybe never really did. Your old thinking probably got you into the mess you’re in. You need to make a fundamental change to the way you think, and can’t go back.

There is often an unavoidable event that triggers this sort of learning. Maybe your business fails, and you see how it was obvious there were problems if only you’d seen them. Or credit card details are stolen from your website. You can’t say it was someone else’s fault. Maybe your partner leaves you unexpectedly, and once you see the reason you kick yourself for not seeing it.

Once you’ve learned something like this, it’s hard to even imagine what it would be like not to know. The past is another country.

I think this sort of unavoidable situation that can’t be explained by your current knowledge is often the catalyst for double loop learning. But our brains don’t like the cognitive dissonance. They would rather explain events any other way.

This is why we get angry when playing Bongard games when we don’t know the range of answers, and why many companies strategy is to keep doing the same thing.

Anti Fragile People

Some event that could break a fragile version of ‘us’, or be endured by a robust ‘us’ actually makes us stronger when we learn from it.

The event needs to be capable of hurting us – or making us angry enough to put up defences.

So what is stopping us getting over the double loop learning wall and being Anti Fragile? And what can help us over the wall?

Single loop learning feels so much nicer than double loop learning. Double loop Learning required we get past the cognitive bias that says we have a consistent explanation for how the bits of the world we care about works.

What’s stopping us?

We’re stopping ourselves.

What can help us?

Unavoidable feedback from hard failures can make us stronger. The feedback can also be endured or can break us. Exposure to the thinking that comes from hard failure makes us uncomfortable.

In many circumstances, feedback structured in a way that helps us develop, by making it hard for us to ignore. The best example of this is Clean Feedback, by Caitlin Walker.

That’s another post.

Really, what’s stopping us?

There is a useful (but ultimately wrong) model of how our brains work, called the Triune Brain. This suggests that there are 3 areas, or thinking states that we use. The lowest brain is the Reptilian brain. This is the fight, flight or freeze response. Knowing we are physically safe keeps this brain quiet. Feeling unsafe activates this brain. A fight also can mean get angry…

If our Reptilian Brain is happy we can use the Mammalian Brain. This brain has higher functions and is kept happy by knowing the rules. This can be social rules, like where the loos are, if you can just go and get a drink, and what time lunch is. Not knowing the rules puts you in the Mammalian brain.

If you’re safe, and you know the rules, then you can use the Neo-Cortex, or learning brain. I’m going to suggests that this is more accurately called the Single Loop Learning Brain. You can learn a new Language, or how to use your current skills better. It’s mostly saying “Don’t worry, you know the answers. No dissonance here.”

To put all this together

Example 1: Zendo

We’re playing a game. It’s supposed to be fun. But if we only know a few of the possible answers. We don’t know the rules. We’re in the Mammalian brain. We’re not happy. It’s not terrible, but it’s not exactly fun either. We want to be in our Neo Cortex, getting the answers right. Being an expert.

Before we play again we look at all the cards with the answers on. The game is now to remember these and pick the right one. You can do this, we’re an expert. It’s now more fun, but we’ve limited our creativity.

Example 2: Strategy

With our full list of potential strategies, we’re working in our neo-cortex. An expert doing pattern matching.

Is a complete list a barrier to your brain double loop leaning? During analysis do we come up with new strategies that are likely to be wrong in the particular example, or do we match what we know?

Are strategy consultants experts? How would they see a brand new strategy if it presented itself?

Example 3 Credit Card Harvesting

This article is delicious. David sets up the reader with a situation that’s hard to dismiss out of hand. It’s a challenge to the expert. He then uses the experts’ heuristics and shows how they are wrong. I imagine there may be a few angry readers.

Has this article about double loop learning offered any specific examples of double loop learning to the readers? Will it change anyone’s mind? Does it make people angry? Why is this article wrong?

So what?

To wrap all this up

- There are open and closed problems

- These can be played using Zendo, and the differences can be seen

- Being an expert has some potentially negative consequences

- Knowing the language to describe your problem could mean you miss things you don’t have a name for

- Is this a difference described by being an engineer, and a scientist?

- Unless using something like Clean Feedback, you need to be uncomfortable to experience double loop learning – learning that challenges your current way of doing things.

- If you avoid discomfort you’re unlikely to learn how to act in the world better

- What else can we do to learn about our understanding of the world?

- A colleague suggested Drugs…

- Talking to people we disagree with and understanding how they are cognitively consistent (or right…). I guess this can also be combined with the drugs 😉

- What does this mean for our facebook and twitter filter bubble?

- When someone makes us angry is it a chance to learn?

- Or do we block and unfriend?

Knowing if the problem you’re solving is likely to be open or closed is a great starting point.

So lastly there are the Strategy problems I mentioned. Are they an open problem where new strategies are being thought up, or a closed one where they are all in a big book of experts strategy?

This may be a good direction to look in the future.

Pingback: Getting the Finger Pointing Right. How to fix tech problems under pressure. | Make 10 Louder