What Wikipedia Taught Me About My Grandfather

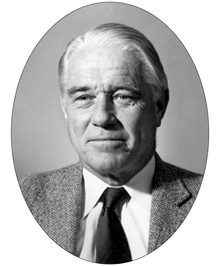

To me, he was Grandpa Freddy. To the scientific community, he was Frederic M. Richards, a leading biophysics thinker—something I never knew until I visited his entry after he died.

On June 6, 1989, my grandfather looked at me and lifted his spoon. Between us was a bowl of lightly sugared fruit. He took a breath, stared down the 9-year-old across from him and said, “Go!” Less than a minute later spoons were down and very likely he had won. I don’t know why he challenged me to see who could eat dessert faster. I doubt he knew. Challenges were fun and he liked fun. That we were in Robert Henry’s, one of the fanciest restaurants in the state of Connecticut, that it was his 30th wedding anniversary, that the contest had no rule and no winner, those didn’t matter. The most important thing, in his universe, was to have fun.

On January 12, 2009, the day after he passed away, I Googled him. It seemed like the thing to do. My mother had always talked about how he was a big-name scientist and had done important things, but in the way of a snotty kid who had been reading about truly important scientists like Einstein I assumed she was trying to aggrandize him, to catch a bit of invented glory from 3000 miles away. She told me he went to the grave disappointed he hadn’t won the Nobel Prize. I used to tell that to people at parties as an example of how absurd academics’s expectation of themselves are.

At the time he had a Wikipedia page—a stub. Two quick paragraphs and a list of papers. It started, “Richards' most notable accomplishment was when through a simple experiment, he changed the current view that proteins were colloids into the modern view that proteins are well-ordered structures.” By then I had become a physicist myself and I knew exactly what that sentence meant, particularly because I didn’t understand a word of it. It meant that he had done good, solid work. Good enough that another biologist had dashed off a quick entry, but not important enough for someone to translate it even far enough for a physicist to understand.

I was stunned, then, a couple months ago when I idly Googled him again and discovered that the Wikipedia entry for Frederic M. Richards was now over 5,300 words. The stub had turned into a GA-Class biography (“Good Article,” the second best classification possible) and was the flagship biography of something called “WikiProject Biophysics.”

Suddenly, there was so much—sections, subsections, a personal biography, research highlights (the bulk of the article), and a references list long enough to overfill my laptop screen. I sat there not even reading, just staring. It looked like any of the hundreds of other Wikipedia biographies I’ve read for actually important people, but it was about someone I knew. Or thought I knew.

I thought I would know most of what a Wikipedia biographer might about my own grandfather. Even if I only saw him every two years, I felt like I should have been able to read along nodding. Oh yes, he chose MIT over Yale. Right, the sailing. Oh yeah, the “Richards box.” But none of it looked familiar. That’s not how lives work. We have lives with our friends and our family and our colleagues, and often they’re completely separate.

To me Frederic M. Richards was Grandpa Freddy, a jolly man who always wore a silly brown jacket with elbow patches, who delighted in showing me how to spin the lazy Susan at the breakfast table, who insisted I help him move a one-ton rock up his path, who challenged me to fruit-eating contests. To his parents and siblings he was the weird youngest son. To a generation of biophysicists he was, apparently, a defining thinker.

One of the wonderful parts of Wikipedia is that not only can you see the revision history, you can also see who made the changes. It turns out that in this case, almost the entire article was written by “dcrjsr,” or Jane S. Richardson, a 73-year-old biophysicist at Duke University and past president of the Biophysical Society. Richardson is also the main driver behind WikiProject Biophysics—one that currently lists 13 categories and almost 800 articles, including Membrane Potential, Physics of Skiing, and CACNA2D1. Of those 800 articles, three are certified as Featured Articles and six as Good Articles. Only one of those Good Articles is a biography. That biography is of my grandfather.

So I called Richardson to find out how that happened.

Richardson is an important woman. It took us some time to find a time to talk between her research and speaking engagements. But once we did connect she was happy to talk. As busy as she was, though, editing Wikipedia was something she cared about a lot. “This is one of the things I’m looking forward to when I retire,” she told me.

Richardson started the Biophysics project because she felt that working on Wikipedia entries was something all scientists should be doing. “All of us refer to [Wikipedia],” she said.” Early on we were really negative about it, but most of us aren’t any more. In general it really is the place to start whenever you’re looking up something.” She also said the article would likely have influences she could never predict. I’m an example. “I would never have thought that this biography would be illuminating to his grandson,” she said.

So Richards set about improving the biophysics articles out there.

To figure out where to start, she sat down with her husband (also a biophysicist), and they thought about their own careers. “There were three people who had really influenced us very strongly,” she says. “The other two had pretty decent Wikipedia pages, and Fred’s just seemed terrible.” In addition, it turns out Fred had written a short autobiography, giving her enough material to work with. So Richardson learned the criteria for a Good Article, set to work on writing more about Fred, got feedback, and over time it became the most developed and cleanest of the WikiProject Biophysics biographies.

There are at least three men with Nobel Prizes who have worse Wikipedia entries than my grandfather, including Linus Pauling who won twice. One of those men, Christian Anfinson, who won his Nobel in 1982 came up when I looked through the references. Fred received obituaries in both Science and Nature, the two top journals in all of science. In this new, extended explanation of Fred’s research, Thomas Steitz wrote in Nature, “It anticipated… a finding that resulted in the award of a Nobel Prize to Christian Anfinsen in 1972—a prize that Richards could arguably have shared.”

It turns out, all these years I’ve been using him as an example of scientific hubris, I was wrong. He wasn’t absurd with his expectations, nor was my mom with her praise. He nearly did get the Nobel Prize.

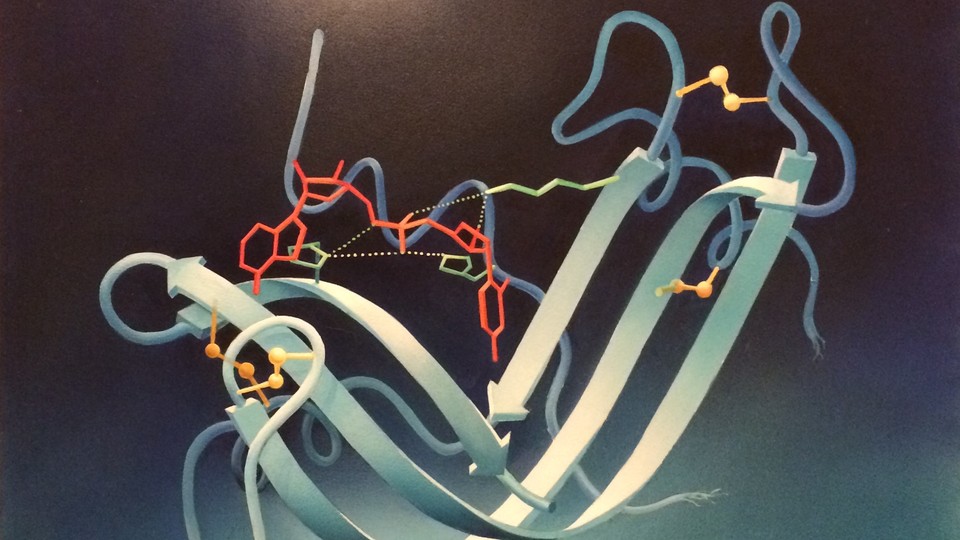

I had never dug into his actual work, even when I became a scientist myself. It was too far away and in another field. It turns out to be pretty incredible. He studied proteins, and when he began his work people already knew that they were vitally important for life. By 1957, they knew that proteins were long chains of smaller molecules, called amino acids. (It would later turn out that proteins are even more important than people thought—they would find that DNA, the master code for everything that happens in the body, is a set of instructions for how to build proteins out of amino acids.) What they didn’t know was how proteins behaved inside the cell.

Grandpa Freddy’s research focused on a specific protein named ribonuclease (he used a version distilled from cow pancreases, but humans have it too), whose function is to break up certain other molecules when they’re not longer required. He wanted to know how it was held together. To find out, he took the ribonuclease and broke it in two, one small part with 20 amino acids, and one big part with 104. When he separated those two bits, he found that they no longer functioned—they were biologically dead. Then, he put them back together. When he did, the ribonuclease was back in action, able to break the other molecule again.

That doesn’t sound like much. In fact, it sounds incredibly simple and obvious— take something apart, it doesn’t work, put it back together, and it does! But, apparently, this was stunning news.

This is because, at the time, the prevailing view was that proteins were so big they had to be big floppy globs of identical smaller molecules, and it shouldn't matter too much if there are 124 or 104 copies. If that were true, each bit of the protein should be sort of functional on its own. If you have one piece of a protein you don’t need to know the other parts to know what it does, and hence what it is.

But Grandpa Freddy’s work showed that that wasn’t true. He showed that a protein was a single, extremely complicated molecule, and that every bit was vital for understanding the structure and function of the whole.

In my current job I have people tell true, personal stories about science in their lives. I interact with a tremendous number of scientists at all stages of their career, as well as comedians, artists, writers, and others. Except for a few close friends and family, almost everyone I know, I know through their professional life—their Twitter bio, their websites, their work. I see a facet, a piece of who they are.

How much would my view change if I knew every aspect of their life? Probably a lot, but unlike proteins I can’t crystallize them and use x-ray diffraction to work out their structure. I can’t even do that with my own family. All I can do is keep finding pieces, adding them, and seeing the new picture, unable to see the whole picture, who they really are.

When I was 15, my mom and I went to a Richards family reunion. I didn’t really know anyone, so I was standing outside on a porch, holding a glass of Coke. Grandpa Freddy came out in his signature brown tweed jacket with elbow patches, walked over, put his arm around me, pointed to the Coke, and said, “I’m going to tell you the single most important thing in your life. Develop a taste for tonic water.”

I just stood there, waiting for an explanation. I had no idea what that meant.

He went on, “Here’s what you do. You’re at a party, you go to the bar and get a gin and tonic. You make the circuit around the party and make sure everyone knows you’re drinking a gin and tonic. Then you keep going back to the bartender and asking for more tonic water. Everyone will be amazed at how much you can drink.” And then he walked off.

In the years since, that episode has become the single thing I remember about him most—more than his descriptions of sailing, more than his delight at using the lazy Susan at the breakfast table, more than the dessert race. It’s a fragment from the other part of his life, in which he had to impress other scientists at cocktail parties, that slipped into mine. I don’t live in a world where that would ever be useful; none of my friends or colleagues care how much or if I drink. But it hints at his, at the era he grew up in, and the circles he moved in.

That story isn’t in the Wikipedia page, of course. Those pages are written to show a public face, to explain what they’re known for and give a hint of who they are. But of course they don’t show the whole thing, and in their private lives people can be completely different. We all know that, even if we occasionally forget. But we also forget that what we know of our family is incomplete. A sense I’ve had my whole life of who my grandfather is can be transformed by the addition of a single fact from a stranger writing on the Internet. All the pieces are needed to see the whole structure. The problem with people, as opposed to proteins, is that we never know for sure we have all the pieces.