Plan to revive 1970s UK satellite

- Published

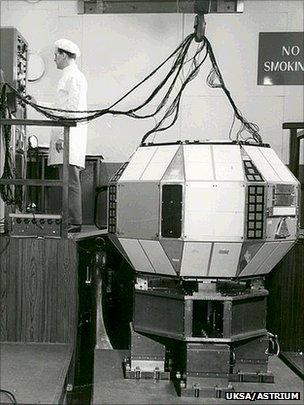

A group of scientists and engineers is working on an ambitious project to revive a unique UK satellite - still in orbit after almost 40 years.

When the Prospero spacecraft was launched atop a Black Arrow rocket on 28 October 1971, it marked the end of an era. A very short era.

Prospero was the first UK satellite to be launched on a UK launch vehicle; it would also be the last.

Ministers had cancelled the rocket project in the run up to the flight.

However, as the Black Arrow was ready, the programme team decided to go-ahead anyway. Prospero was blasted into orbit from the remote Woomera base in the Australian desert. It turns out, the satellite is still up there.

Carrying a series of experiments to investigate the effects of the space environment, the satellite operated successfully until 1973 and was contacted annually until 1996.

Now, a team led by PhD student Roger Duthie from University College London's Mullard Space Science Laboratory in Surrey is hoping to re-establish communications in time for the satellite's 40th anniversary.

"First, we have to re-engineer the ground segment from knowledge lost, then test the communications to see if it's still alive," Duthie told the Space Boffins podcast.

"Then we can have drinks and champagne!"

But none of this is easy (apart from maybe the champagne bit). The satellite was built by Space Department at the Royal Aircraft Establishment in Farnborough but the department was broken up long ago and the codes to contact Prospero were missing.

"The technical reports made in the 1970s were thought to have been lost," explained Duthie. "We talked to the people involved in Prospero, searched through dusty boxes in attics and tried the library at Farnborough."

Eventually they discovered the codes typed on a piece of paper in the National Archives at Kew, London.

But even with the codes, the engineers still have to build equipment to "talk" to the satellite and win approval from the broadcast regulator Ofcom to use Prospero's radio frequencies - these days being employed by other satellite operators.

Once this "ground segment" is complete, the plan is to test the technology to see if it is still possible to communicate with Prospero before attempting any public demonstration. If the satellite is still alive, some of the experiments might even be working.

"It's an artefact of British engineering; we should find out how it's performing," said Duthie.

If it works, Duthie's team can call themselves the world's first astro-archaeologists.

Richard Hollingham is a freelance science writer and broadcaster, and the co-presenter of the Space Boffins podcast.

- Published24 May 2011

- Published9 November 2009

- Published3 February 2009