Abstract

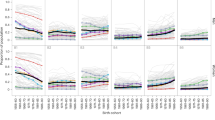

Using educational status in England from 1170 to 2012, we show that the rate of social mobility in any society can be estimated from knowledge of just two facts: the distribution over time of surnames in the society and the distribution of surnames among an elite or underclass. Such surname measures reveal that the typical estimate of parent–child correlations in socioeconomic measures in the range of 0.2–0.6 are misleading about rates of overall social mobility. Measuring education status through Oxbridge attendance suggests a generalized intergenerational correlation in status in the range of 0.70–0.90. Social status is more strongly inherited even than height. This correlation is unchanged over centuries. Social mobility in England in 2012 was little greater than in preindustrial times. Thus there are indications of an underlying social physics surprisingly immune to government intervention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

There are exceptions in which children took the surname of the mother, such as illegitimate children, but these can be seen to be a very small share of all births. Until recently more than 99% of children in England had their surname registered as that of the father.

In psychometric terms, underlying status is a latent variable.

We use the English convention of referring to Oxford and Cambridge together as Oxbridge.

Ashton (1977) estimates that students recorded for Oxford in 1170–1500 were only 20–25% of actual numbers.

To eliminate surnames for which most of the holders would be non-English, the rare surname samples excluded as far as possible names whose population concentrations lay outside England. Thus all names beginning with “Mc” or “Mac” or “O’” were removed since they are of Scottish or Irish origin. Also, any surname with more than 40 occurrences in the 1881 census was removed if its frequency in 2002 was more than 2.5 times the earlier frequency (the expected frequency would be 1.85). A check using surnames represented by 500 or fewer holders in 1881 found that even including all surnames in the sample did not change the estimated b by much.

The first period, 1800–1829, in which the elite surnames are identified, cannot be used to estimate b, since in this period we do not have the expectation that \( {\overline{y}}_{kt}={\overline{x}}_{kt} \), unlike in Eq. (7). In this first period the average status of the surnames is overestimated by their relative representation at Oxbridge, since the surnames included will tend in that period to have a positive random component in terms of their educational status.

References

Ashton, T. S. (1977). Oxford’s Medieval alumni. Past & Present, 74, 3–40.

Atkinson, A., Maynard, A., & Trinder, C. (1983). Parents and children: Incomes in two generations. London: Heinemann.

Clark, G., & Cummins, N. (2014a). Inequality and social mobility in the Industrial Revolution era. In R. Floud, J. Humphries, & P. Johnson (Eds.), The Cambridge economic history of modern Britain. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Clark, G., & Cummins, N. (2014b). What is the true rate of social mobility? Surnames and social mobility in England, 1830–2012. Economic Journal. doi:10.1111/ecoj.12165.

Clark, G., & Cummins, N. (2014c). Malthus to modernity: England’s first demographic transition, 1760–1800. Journal of Population Economics. doi:10.1007/s00148-014-0509-9.

Clark, G., Cummins, N., Diaz Vidal, D., Hao, Y., Ishii, T., Landes, Z., Marcin, D., Mo Jung, K., Marek, A., & Williams, K. (2014). The son also rises: 1,000 years of social mobility. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Clark, G., & Hamilton, G. (2006). Survival of the richest. The Malthusian mechanism in pre-industrIal England. Journal of Economic History, 66(3), 707–36.

Corak. M. (2012) Inequality from generation to generation: The United States in comparison. In R. Rycroft (Ed), The economics of inequality, poverty, and discrimination in the 21st century. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO.

Dearden, L., Machin, S., & Reed, H. (1997). Intergenerational mobility in Britain. Economic Journal, 107, 47–66.

Ermisch, J., Francesconi, M., & Siedler, T. (2006). Intergenerational mobility and marital sorting. Economic Journal, 116, 659–679.

Galton, F. (1869). Hereditary genius: An enquiry into its laws and consequences. London: Macmillan.

Galton, F. (1889). Natural inheritance. London: Macmillan.

Greenstein, D. (1994). The junior members, 1900–1990: a profile. In B. Harrison (Ed.), The history of the University of Oxford, volume VIII. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Grönqvist, E., Öckert, B., Vlachos, J. (2011) The intergenerational transmission of cognitive and non-cognitive abilities. IFN Working Paper No. 884. Available at doi: 10.2139/ssrn.2050393.

Harbury, C., & Hitchens, D. (1979). Inheritance and wealth inequality in Britain. London: Allen and Unwin.

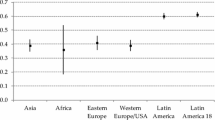

Hertz, T., Jayasundera, T., Piraino, P., Selcuk, S., Smith, N., Verashchagina, A. (2007) The inheritance of educational inequality: International comparisons and fifty-year trends. The B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy 7, Article 10.

Keats-Rohan, K. S. B. (1999). Domesday people: A prosopography of persons occurring in English documents 1066–1166. Woodbridge: Boydell Press.

Long, J. (2013). The surprising social mobility of Victorian Britain. European Review of Economic History, 17(1), 1–23.

Pearson, K., & Lee, A. (1903). On the laws of inheritance in man, I: inheritance of physical characters. Biometrika, 2, 357–462.

Schurer, K., & Woollard, M. (2000). 1881 Census for England and Wales, the Channel Islands and the Isle of Man (enhanced version) [computer file]. Genealogical Society of Utah, Federation of Family History Societies, [original data producer(s)]. Colchester, Essex: UK Data Archive [distributor]. SN: 4177, doi:10.5255/UKDA-SN-4177-1.

Silventoinen, K., et al. (2003). Heritability of adult body height: a comparative study of twin cohorts in eight countries. Twin Research, 6, 399–408.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Clark, G., Cummins, N. Surnames and Social Mobility in England, 1170–2012. Hum Nat 25, 517–537 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12110-014-9219-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12110-014-9219-y