In the 1800s, scientists imagined that life was brought to Earth by a rock that had been knocked off of a distant, life-filled planet. Now, over 100 years later, we are able to test this idea of “panspermia”—by sending life away from Earth and seeing just how well it can fare.

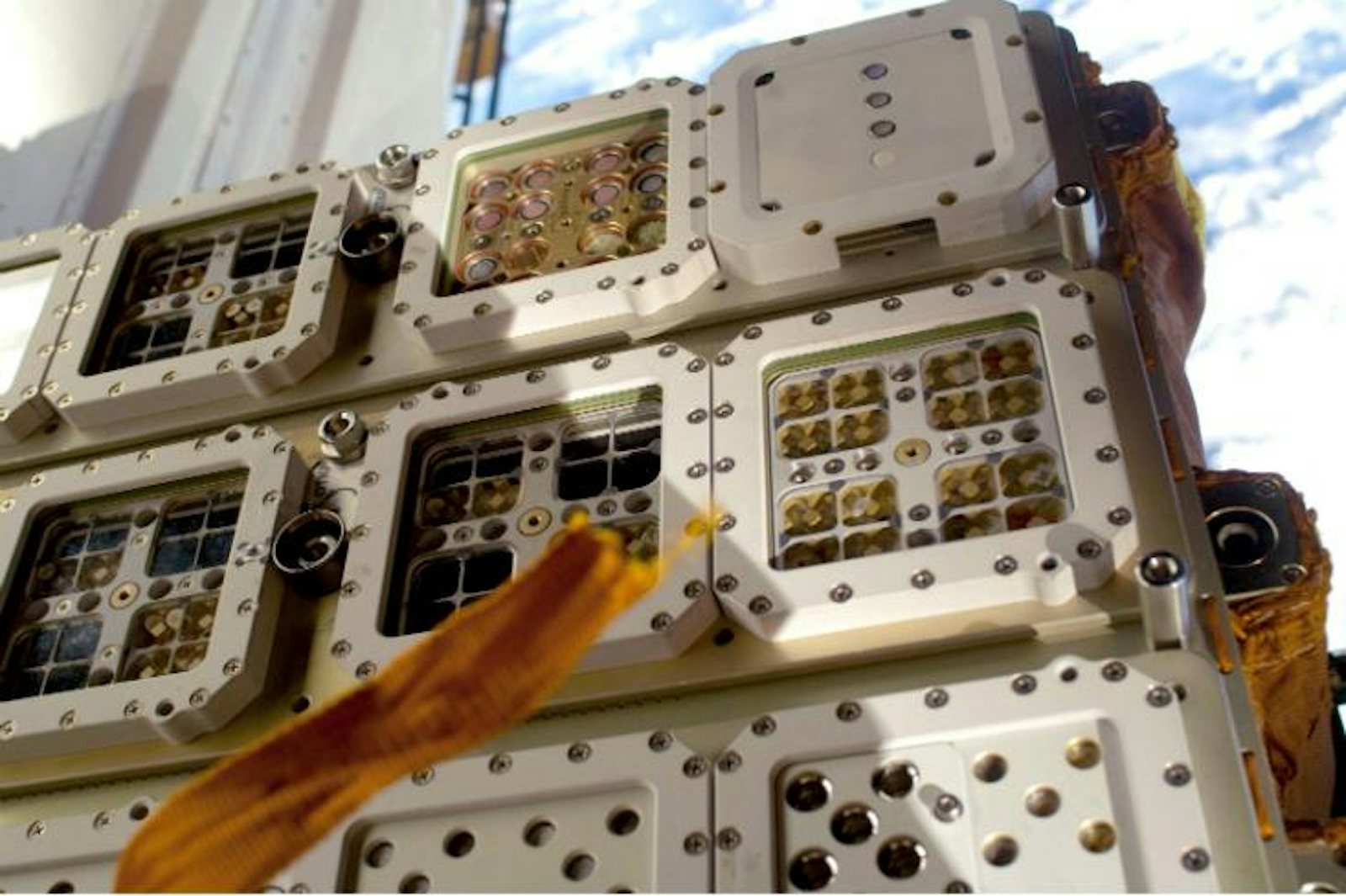

Over the past several years, space agencies have been sending small colonies of microbes from some of the harshest environments on our planet to space to see if they can survive a trip to the Moon or even Mars. Last month two Russian astronauts spacewalked out of the International Space Station and installed a special piece of equipment to its exterior. The module, called EXPOSE-R2, features an array of small containers that contain samples from four major varieties of life: bacteria, fungi, archaea, and plants. Unlike astronauts, who take extreme precautions to protect themselves from the hazards of outer space, these bio-suitcases are placed on the exterior of the station for months at end, with little protection. The module is also fitted with sensors that record fluctuations in pressure, temperature, and solar radiation, which provide a record of the organisms’ journey.

The list of challenges for surviving in space is long. It’s not just the obvious lack of oxygen—there is also ionizing solar radiation and freezing temperatures, not to mention the absence of food and water in the unending vacuum.

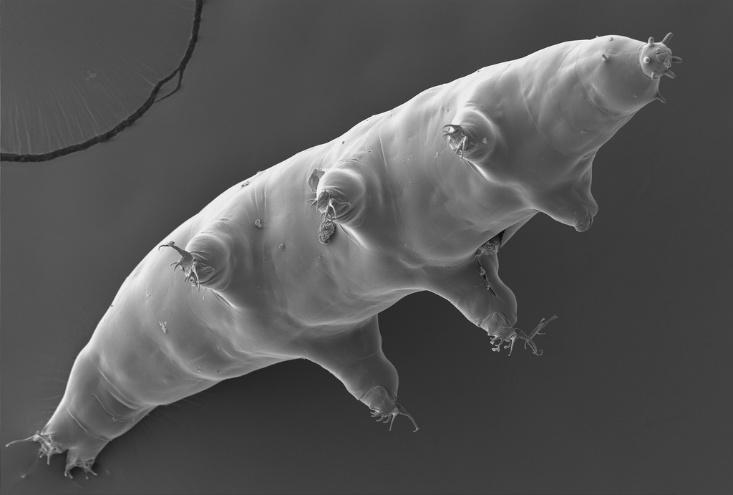

In 2007 two species of tardigrades (R. coronifer and M. tardigradum), also called water bears, withstood these challenges during a 10-day trip, and earned a reputation as some of the toughest known animals. Tardigrades are microscopic invertebrates that had long been known to survive in extreme conditions, from icy shelves in Antarctica to the deep waters of the Gulf of Mexico, but their stay on the ISS made them even more remarkable. They aren’t the only space-faring species. Lichen, a hairy-looking marriage of a fungus with an algae or cyanobacteria (bacteria that practice photosynthesis), grow in some of Earth’s harshest environments, and cover an estimated 6 percent of the planet’s land surface. One particular species, X. elegans, managed to survive on the outside of the ISS for 18 months. In a later mission, a cyanobacterium taken from the cliffs in a fishing village in England also withstood the harsh conditions on the ISS, for a little less than two years.

We still don’t completely understand how these organisms hold out in the void, but researchers know some of their tricks. Firstly, both tardigrades and lichen have evolved to dry themselves for extended periods of time. Lichen are poikilohydric—water flows into and out of their bodies, safely coming to equilibrium with the environment. Tardigrades can survive in a desiccated, inactive state. Lowering the water content allows them to halt their metabolism and conserve their energy; when conditions improve, they start right back up. Humans, in contrast, are around 60% water, and we cannot deviate much from that level.

Lichen sent up in space also produce high amounts of compounds like parietin, a photo-protective pigment that protect it from the Sun’s UV radiation. Researchers found that the layered structure of the lichen’s body, the thallus, also helps screen out UV rays and reduce their damaging effects. Many lichen and cyanobacteria evolved to live on exposed rock surfaces, instead of in protected pores and crevices, which helped them develop robust defenses against extreme conditions.

While the ISS has hosted these official research projects, it may also be the site of an unintentional experiment in space biology: Russian cosmonauts recently announced that they found stowaway plankton sticking to the windows of the station. The report has yet to be confirmed, and NASA seems skeptical. But it does again raise the question, first posed centuries ago, of how many beings out there can survive the vast nothingness of space, bouncing around and spreading life from one world to another.

Manasi Vaidya is a science journalist based in New York City who covers biology and health. Follow her on Twitter at @manasivaidya22.