It was supposed to be a "killer app," but a system deployed to volunteers by Mitt Romney's presidential campaign may have done more harm to Romney's chances on Election Day—largely because of a failure to follow basic best practices for IT projects.

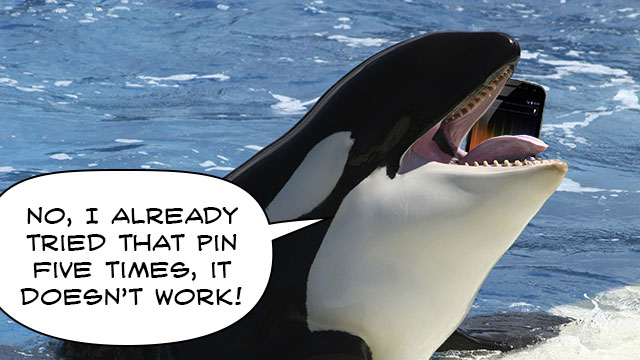

Called "Orca," the effort was supposed to give the Romney campaign its own analytics on what was happening at polling places and to help the campaign direct get-out-the-vote efforts in the key battleground states of Ohio, Florida, Pennsylvania, Iowa, and Colorado.

Instead, volunteers couldn't get the system to work from the field in many states—in some cases because they had been given the wrong login information. The system crashed repeatedly. At one point, the network connection to the Romney campaign's headquarters went down because Internet provider Comcast reportedly thought the traffic was caused by a denial of service attack.

As one Orca user described it to Ars, the entire episode was a "huge clusterfuck." Here's how it happened.

Develop in haste, repent at leisure

The Romney campaign put a lot of stock in Orca, giving PBS NewsHour an advance look at the operation on November 5. But according to volunteers who saw and used the system, it was hardly a model of stability, having been developed in just seven months on a lightning schedule following the Republican primary elections. Orca had been conceived by two men—Romney's Director of Voter Contact Dan Centinello and the campaign's Political Director Rich Beeson. It was named in honor of the killer whale as an allusion to the Obama campaign's own voter identification program, code-named Narwhal; orcas are the top predator of narwhals, Romney campaign staffers explained, and they were preparing to outshine the Democratic voter turnout effort.

As Romney's Communications Director Gail Gitcho put it in the PBS piece, "The Obama campaign likes to brag about their ground operation, but it's nothing compared to this."

To build Orca, the Romney campaign turned to Microsoft and an unnamed application consulting firm. The goal was to put a mobile application in the hands of 37,000 volunteers in swing states, who would station themselves at the polls and track the arrival of known Romney supporters. The information would be monitored by more than 800 volunteers back at Romney's Boston Garden campaign headquarters via a Web-based management console, and it would be used to push out more calls throughout the day to pro-Romney voters who hadn't yet shown up at the polls. A backup voice response system would allow local poll volunteers to call in information from the field if they couldn't access the Web.

But Orca turned out to be toothless, thanks to a series of deployment blunders and network and system failures. While the system was stress-tested using automated testing tools, users received little or no advance training on the system. Crucially, there was no dry run to test how Orca would perform over the public Internet.

Part of the issue was Orca's architecture. While 11 backend database servers had been provisioned for the system—probably running on virtual machines—the "mobile" piece of Orca was a Web application supported by a single Web server and a single application server. Rather than a set of servers in the cloud, "I believe all the servers were in Boston at the Garden or a data center nearby," wrote Hans Dittuobo, a Romney volunteer at Boston Garden, to Ars by e-mail.

Throughout the day, the Orca Web page was repeatedly inaccessible. It remains unclear whether the issue was server load or a lack of available bandwidth, but the result was the same: Orca had not been tested under real-world conditions and repeatedly failed when it was needed the most.

All tell, no show

Before Election Day, volunteer training at Boston headquarters amounted to a series of 90-minute conference calls with Centinello. Users had no hands-on with the Orca application itself, which wasn't turned on until 6:00 AM on Election Day.

"We asked if our laptops needed to be WiFi capable," Dittuobo told Ars. "Dan Centinello went into how the Garden had just finished expansion of its wireless network and that yes, WiFi was required. I was concerned about hacking, jamming the signal, etc...Then we were told that we would not be using WiFi but using Ethernet connections."

Field volunteers also got briefed via conference calls, and they too had no hands-on with the application in advance of Election Day. There was a great deal of confusion among some volunteers in the days leading up to the election as they searched Android and Apple app stores for the Orca application, not knowing it was a Web app.

John Ekdahl, Jr., a Web developer and Romney volunteer, recounted on the Ace of Spades HQ blog that these preparatory calls were "more of the slick marketing speech type than helpful training sessions. I had some serious questions—things like 'Has this been stress tested?', 'Is there redundancy in place?', and 'What steps have been taken to combat a coordinated DDOS attack or the like?', among others. These types of questions were brushed aside (truth be told, they never took one of my questions). They assured us that the system had been relentlessly tested and would be a tremendous success."

In a final training call on November 3, field volunteers were told to expect "packets" shortly containing the information they needed to use Orca. Those packets, which showed up in some volunteers' e-mail inboxes as late as November 5, turned out to be PDF files—huge PDF files which contained instructions on how to use the app and voter rolls for the voting precincts each volunteer would be working. After discovering the PDFs in his e-mail inbox at 10:00 PM on Election Eve, Ekdahl said that "I sat down and cursed, as I would have to print 60+ pages of instructions and voter rolls on my home printer. They expected 75 to 80-year old veteran volunteers to print out 60+ pages on their home computers? The night before election day?"

Invalid passwords, crashing servers

When the Romney campaign finally brought up Orca, the "killer whale" was not ready to perform. Some field volunteers couldn't even report to their posts, because the campaign hadn't told them they first needed to pick up poll watcher credentials from one of Romney's local "victory centers." Others couldn't connect to the Orca site because they entered the URL for the site without the https:// prefix; instead of being redirected to the secure site, they were confronted with a blank page, Ekdahl said.

And for many of those who managed to get to their polling places and who called up the website on their phones, there was another, insurmountable hurdle—their passwords didn't work and attempts to reset passwords through the site also failed. As for the voice-powered backup system, it failed too as many poll watchers received the wrong personal identification numbers needed to access the system. Joel Pollak of Briebart reported that hundreds of volunteers in Colorado and North Carolina couldn't use either the Web-based or the voice-based Orca systems; it wasn't until 6:00 PM on Election Day that the team running Orca admitted they had issued the wrong PIN codes and passwords to everyone in those states, and they reset them. Even then, some volunteers still couldn’t login.

In Boston, things weren't much better. Some of the VoIP phones set up for volunteers were misconfigured. And as volunteers tried to help people in the field get into the system, they ran into similar problems themselves. "I tried to login to the field website," Dittuobo told me, "but none of the user names and passwords worked, though the person next to me could get in. We had zero access to Iowa, Colorado, North Carolina, and Pennsylvania. Seems like the only state that was working was Florida."

As the Web traffic from volunteers attempting to connect to Orca mounted, the system crashed repeatedly because of bandwidth constraints. At one point the network connection to the campaign's data center went down—apparently because the ISP shut it off. "They told us Comcast thought it was a denial of service attack and shut it down," Dittuobu recounted. "(Centinello) was giddy about it," he added—presumably because he thought that so much traffic was sign of heavy system use.

Flying blind

As the day wore on and information still failed to flow in from the field, the Romney campaign was flying blind. Instead of using Orca's vaunted analytics to steer their course, Centinello and the rest of Romney's team had no solid data on how to target late voters, other than what they heard from the media. Meanwhile, volunteers like Ekdahl could do nothing but vote themselves and go home.

This sort of failure is why there's a trend in application testing (particularly in the development of public-facing applications) away from focusing on testing application infrastructure performance and toward focusing on user experience. Automated testing rigs can tell if software components are up to the task of handling expected loads, but they can't show what the system's performance will look like to the end user. And whatever testing environment Romney's campaign team and IT consultants used, it wasn't one that mimicked the conditions of Election Day. As a result, Orca's launch on Election Day was essentially a beta test of the software—not something most IT organizations would do in such a high-stakes environment.

IT projects are easy scapegoats for organizational failures. There's no way to know if Romney could have made up the margins in Ohio if Orca had worked. But the catastrophic failure of the system, purchased at large expense, squandered the campaign's most valuable resource—people—and was symptomatic of a much bigger leadership problem.

"The end result," Ekdahl wrote, "was that 30,000+ of the most active and fired-up volunteers were wandering around confused and frustrated when they could have been doing anything else to help. The bitter irony of this entire endeavor was that a supposedly small government candidate gutted the local structure of [get out the vote] efforts in favor of a centralized, faceless organization in a far off place (in this case, their Boston headquarters). Wrap your head around that."

Republican campaigners will undoubtedly try to wrap their heads around it for some time to come.

reader comments

358