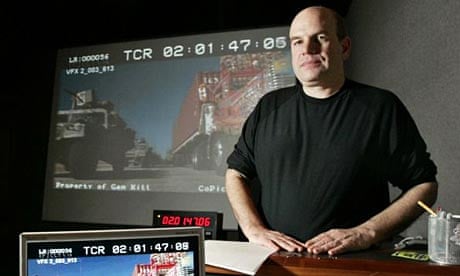

People are occasionally surprised, David Simon says, to find that he still lives in Baltimore, the city that is the lead character in his epic television series The Wire. They assume that the man behind all those box sets would have found himself a luxury penthouse in LA, or Manhattan at least, far from the devastated neighbourhoods his show portrays. But on a cold, bright morning at the headquarters of his production company in downtown Baltimore, he seems as enmeshed as ever in the life of the city - bemoaning the latest antics of the police department and the failure of the Baltimore Sun, his former employer, to cover them. "If I want to find out what's going on in this city, I've got to go to a fucking bar and talk to a police lieutenant and take notes on a cocktail napkin," he says. Simon is 48, bald and stocky, and prone to grumbling aggressively in a manner that is, for some reason, wholly likable. "That's what passes for high-end journalism in Baltimore these days."

One irony of The Wire's global success is that there are now, presumably, plenty of middle-class Britons more familiar with the drugs economy, failing schools and corrupt politicians of Baltimore than they are with any part of inner-city Britain. So faithful is The Wire to the specific vernacular of its setting, indeed, that there may be Londoners or Mancunians whose knowledge of west Baltimore drugs slang exceeds that of dealers in Philadelphia or New York.

They will have a new opportunity to embellish their vocabularies next month with the first UK publication of The Corner, the 1997 non-fiction book that inspired The Wire. Written by Simon and his collaborator Ed Burns, a former Baltimore police detective, it is a forensic document of one year in the inner city, told through the prism of a single street corner, and the addicts and dealers for whom it's the frontline in the struggle to survive. The publication is part of a high-profile year for Simon in Britain: he will appear at this year's Hay literary festival, while BBC2 will give The Wire its first airing on mainstream television.

Simon purports to be amused by his British success - "It's hilarious to me that there are two people walking through Hyde Park right now, arguing about The Wire" - but it would be wrong to imply he's surprised by it. Modesty isn't part of the Simon repertoire. He freely describes The Wire as revolutionary television, capturing "the truth" about the "universal themes" of life in the era of unrestrained capitalism; you sense that, ultimately, he considers the global adulation only fitting. When people call The Wire Shakespearean, he demurs, but only because he considers it a Greek tragedy instead: Aeschylus updated, with urban institutions as the Olympian gods, destroying human lives on a whim. "It's the police department, or the drug economy, or the political structures, or the school administration, or the macroeconomic forces that are throwing the lightning bolts and hitting people in the ass for no decent reason," he has said. (In a show loaded with symbolism, it's no coincidence that the coldest expression of pure capitalism in The Wire is the criminal mastermind of season two, The Greek.) You can watch The Wire, of course, as no more than a gritty soap opera, charting the lives of the alcoholic-but-brilliant detective Jimmy McNulty, the sociopathic kingpin Marlo Stanfield or the heartbreaking dope fiend Bubbles. But don't imagine Simon isn't also operating on another plane entirely.

It's part of the price of admission to Simon's worlds, both fictional and non-fictional, that you'll have almost no idea what's going on for the first few episodes, or the first few hundred pages. Turning on the subtitles will help you only marginally with the Baltimore-speak of The Wire; within the first few pages of The Corner, Gary McCullough, the real-life inspiration for Bubbles, is shown concluding that "the issue is 30 on the hype", no explanation provided. The soldiers of Generation Kill - Simon's Iraq war mini-series, based on a Rolling Stone journalist's book-length account of being embedded with the US marines during the 2003 invasion of Iraq - speak for minutes on end in impenetrable military lingo, and Treme, a show about the New Orleans music scene on which he's currently working, promises similarly opaque music jargon. This is quite deliberate. The key principle of Simon's storytelling was encapsulated in a remark that caused raised eyebrows when he uttered it, late last year, on BBC2's Culture Show: "Fuck the average viewer."

When you want to write the truth, Simon argues, writing for those who know nothing sets the bar too low. "That's how they taught us to write at the Baltimore Sun: 'For the average reader with a seventh-grade education.' " But when he took a leave of absence to write Homicide, his account of a year with Baltimore murder detectives - it later became an acclaimed TV drama of the same name - he realised it was time for a new approach. "There came this point where I sat down with all my notebooks and I had to start to write," he says, "when I thought: this whole notion of writing for the person who understands nothing, the average reader ... He has to die! I can't have him in my head. And so the person I started writing for was the homicide detective." He wasn't aiming to please his subjects themselves, he insists; many of the detectives emerge from the book as racist, homophobic, sexist or some mixture of all three. "My guy in my head was some guy in Chicago I'd never met. Not the average reader. Fuck him! I want to write for the guy living the event. When I criticise him, I want him to think, 'That was fair.' When I don't criticise him, I want him to think, 'He gets it.'" Generation Kill, meanwhile, unsparingly presents America's finest fighters as video game-obsessed frat boys. But even though one of them was forced out of his battalion as a result of the original book, Simon maintains that the marines involved are "in virtually every case" happy with their portrayal.

For the average reader or viewer, "the promise is that, as they go along, they'll understand more and more, and maybe by the end they'll understand most if not all of it". This sounds daunting, but watching The Wire or Generation Kill, that's not how it feels: the ingenious effect is to leave the viewer with the smugness-inducing sense of being smarter than before. "I love people who get to the end of the first episode and say, 'That's the show they're calling the greatest show in television? What?'" Simon says. "The first season of The Wire was a training exercise. We were training you to watch television differently."

The startling narrative compression of The Wire and Generation Kill means that no scene is ever a throwaway: miss a 10-second plot point in episode three and you'll regret it in episode nine, when it's suddenly crucial. "Even with shows that are somewhat sophisticated, you can take a phone call, you can have a conversation with your boyfriend or your spouse, and still pretty much grasp the show. The Wire will fuck you if you do that."

Isn't it arrogant to presume to retrain viewers in the art of watching television? "You know what would feel arrogant to me? What would feel arrogant to me would be asking you to spend 10 or 12 hours of your time a year watching my shit, and delivering something where we didn't hold that time precious. Last year, with The Wire and Generation Kill, HBO gave me 17 hours of uninterrupted film - almost $100m of production value. What would be arrogant would be to waste that - to tell anything less than the most meaningful possible story. Whenever I see a good subject ruined with a bad film or a bad book, I feel: shit, now it'll be harder to go back there again. How dare you presume to tell me a story, and then not tell me the best possible story?"

When he started researching The Corner, Simon had covered crime for the Sun for 13 years, but examining the drugs trade from the inside presented fresh challenges: two white guys hanging around the corner of Monroe and Fayette in west Baltimore were hardly inconspicuous. "We were initially regarded by many of the corner regulars as police or police informants," Simon and Burns write. It didn't help that some older dealers remembered Burns from his detective days. The police posed a different problem: those who didn't recognise them kept threatening to arrest them, assuming they were buying drugs; those who did recognise them stopped to chat, incurring the suspicion of locals. It took five months until the corner regulars "were convinced that whatever else we claimed to be, we weren't police. No one could recall seeing us buy or sell anything, nor did we seem to do anything that resulted in anyone getting locked up." By the time The Corner had become first its own mini-series and then, along with Homicide, source material for The Wire, west Baltimore had come on board to the point that throngs of spectators got in the way of filming. According to rumour, real wiretaps went silent during broadcasts, as dealers suspended operations in order to watch.

If there's a fault with Simon's work, it's that his characters can be so compelling, you forget to be angry about the situations he portrays. You find yourself laughing at the war-hardened wisecracks of Generation Kill's Corporal Josh Person, say, or wondering at The Wire's Marlo and his coldblooded cool, without stepping back to take stock of the modern nightmares they're enduring. Simon, on the other hand, is very angry indeed. "You are sitting in the deconstruction of the American Dream," he says, indicating Baltimore. "Which is to say there was a fundamental myth that if you were willing to work hard, support your family, stay away from shit that ain't good for you, you'd do all right. You didn't have to be the smartest guy in the room. The dream wasn't that everyone could get rich. It was that everyone gets to make a living and see the game on Saturday, and maybe, with the help of a government loan or two, your kid'll go to college." His anger is wide-reaching: deprivation in Baltimore, imaginary WMDs in Iraq and Wall Street scandals are all part of the same betrayal - of capitalist institutions "selling people shit and calling it gold".

Simon doesn't respond well to the criticism that perhaps things aren't entirely bad - that his shows' unremitting pessimism distorts a world where some people do defeat the crushing force of social institutions. Last year, the journalist Mark Bowden made that charge in the Atlantic magazine, and Simon hasn't forgiven him. "This premise that The Wire wasn't real because it didn't show people having good outcomes in west Baltimore ... I don't know what to tell him. We didn't spend a series in a cul-de-sac with people barbecuing; it was the story of what's happening at the bottom rungs of an economy where capitalism has been allowed free rein. And if he's telling me it's not happening, I want to take his fucking entitled ass and drive him to west Baltimore and shove him out of the car, at Monroe and Fayette, and say, find your way back, fucker, because you've got your head up your ass at the Atlantic."

Behind Simon's general disillusion is a disillusionment with journalism, the only work he ever wanted to do. Raised in a secular Jewish household in the Washington suburbs, he wrote for his school magazine, then was so busy editing the University of Maryland newspaper that it took him five years to graduate ("with terrible grades"). In his final year he began stringing for the local paper, the Sun; his wife, the novelist Laura Lippman, is another former Sun reporter. The way he tells it, the central betrayal of Simon's life is the gutting of the Sun by profit-obsessed owners and Pulitzer-obsessed editors. One of those reviled executives, Bill Marimow, gets an obnoxious police lieutenant named after him in The Wire; Scott Templeton, the weaselly fabricator of season five, is modelled on a Sun colleague. (Other former staffers describe Simon as a perpetual picker of fights.)

The collapse of the US newspaper industry has left politicians free to pursue their unethical schemes unscrutinised. "The internet does froth and commentary very well, but you don't meet many internet reporters down at the courthouse," he says. "Oh to be a state or local official in America over the next 10 to 15 years, before somebody figures out the business model. To gambol freely across the wastelands of an American city as a local politician! It's got to be one of the great dreams in the history of American corruption."

The way Simon sees it, The Wire and Generation Kill are, above all else, an exercise in reporting: the pulling back of the curtain on the real America that should have been undertaken by newspapers, transposed instead into the multimillion-dollar world of TV drama. "It's fiction, I'm clear about that. But at its heart it's journalistic." Newspapers, he says, launching into a new tirade, "have been obsessed with what they called 'impact journalism' - take a bite-sized morsel of a problem, make a big noise, win a Pulitzer. It was bullshit! But it was the only thing they knew. But what America needed in the last two decades was not 'impact journalism'. What they needed was somebody explaining what the fuck was happening to the country." The phrase he uses to describe the role newspapers should have been playing is also, you can't help feeling, one Simon would like to see as his own epitaph: "A counterweight to bullshit."

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion