How American Politics Went Insane

It happened gradually—and until the U.S. figures out how to treat the problem, it will only get worse.

It’s 2020, four years from now. The campaign is under way to succeed the president, who is retiring after a single wretched term. Voters are angrier than ever—at politicians, at compromisers, at the establishment. Congress and the White House seem incapable of working together on anything, even when their interests align. With lawmaking at a standstill, the president’s use of executive orders and regulatory discretion has reached a level that Congress views as dictatorial—not that Congress can do anything about it, except file lawsuits that the divided Supreme Court, its three vacancies unfilled, has been unable to resolve.

On Capitol Hill, Speaker Paul Ryan resigned after proving unable to pass a budget, or much else. The House burned through two more speakers and one “acting” speaker, a job invented following four speakerless months. The Senate, meanwhile, is tied in knots by wannabe presidents and aspiring talk-show hosts, who use the chamber as a social-media platform to build their brands by obstructing—well, everything. The Defense Department is among hundreds of agencies that have not been reauthorized, the government has shut down three times, and, yes, it finally happened: The United States briefly defaulted on the national debt, precipitating a market collapse and an economic downturn. No one wanted that outcome, but no one was able to prevent it.

As the presidential primaries unfold, Kanye West is leading a fractured field of Democrats. The Republican front-runner is Phil Robertson, of Duck Dynasty fame. Elected governor of Louisiana only a few months ago, he is promising to defy the Washington establishment by never trimming his beard. Party elders have given up all pretense of being more than spectators, and most of the candidates have given up all pretense of party loyalty. On the debate stages, and everywhere else, anything goes.

I could continue, but you get the gist. Yes, the political future I’ve described is unreal. But it is also a linear extrapolation of several trends on vivid display right now. Astonishingly, the 2016 Republican presidential race has been dominated by a candidate who is not, in any meaningful sense, a Republican. According to registration records, since 1987 Donald Trump has been a Republican, then an independent, then a Democrat, then a Republican, then “I do not wish to enroll in a party,” then a Republican; he has donated to both parties; he has shown loyalty to and affinity for neither. The second-place candidate, Republican Senator Ted Cruz, built his brand by tearing down his party’s: slurring the Senate Republican leader, railing against the Republican establishment, and closing the government as a career move.

The Republicans’ noisy breakdown has been echoed eerily, albeit less loudly, on the Democratic side, where, after the early primaries, one of the two remaining contestants for the nomination was not, in any meaningful sense, a Democrat. Senator Bernie Sanders was an independent who switched to nominal Democratic affiliation on the day he filed for the New Hampshire primary, only three months before that election. He surged into second place by winning independents while losing Democrats. If it had been up to Democrats to choose their party’s nominee, Sanders’s bid would have collapsed after Super Tuesday. In their various ways, Trump, Cruz, and Sanders are demonstrating a new principle: The political parties no longer have either intelligible boundaries or enforceable norms, and, as a result, renegade political behavior pays.

Political disintegration plagues Congress, too. House Republicans barely managed to elect a speaker last year. Congress did agree in the fall on a budget framework intended to keep the government open through the election—a signal accomplishment, by today’s low standards—but by April, hard-line conservatives had revoked the deal, thereby humiliating the new speaker and potentially causing another shutdown crisis this fall. As of this writing, it’s not clear whether the hard-liners will push to the brink, but the bigger point is this: If they do, there is not much that party leaders can do about it.

And here is the still bigger point: The very term party leaders has become an anachronism. Although Capitol Hill and the campaign trail are miles apart, the breakdown in order in both places reflects the underlying reality that there no longer is any such thing as a party leader. There are only individual actors, pursuing their own political interests and ideological missions willy-nilly, like excited gas molecules in an overheated balloon.

No wonder Paul Ryan, taking the gavel as the new (and reluctant) House speaker in October, complained that the American people “look at Washington, and all they see is chaos. What a relief to them it would be if we finally got our act together.” No one seemed inclined to disagree. Nor was there much argument two months later when Jeb Bush, his presidential campaign sinking, used the c-word in a different but equally apt context. Donald Trump, he said, is “a chaos candidate, and he’d be a chaos president.” Unfortunately for Bush, Trump’s supporters didn’t mind. They liked that about him.

Trump, however, didn’t cause the chaos. The chaos caused Trump. What we are seeing is not a temporary spasm of chaos but a chaos syndrome.

Chaos syndrome is a chronic decline in the political system’s capacity for self-organization. It begins with the weakening of the institutions and brokers—political parties, career politicians, and congressional leaders and committees—that have historically held politicians accountable to one another and prevented everyone in the system from pursuing naked self-interest all the time. As these intermediaries’ influence fades, politicians, activists, and voters all become more individualistic and unaccountable. The system atomizes. Chaos becomes the new normal—both in campaigns and in the government itself.

Our intricate, informal system of political intermediation, which took many decades to build, did not commit suicide or die of old age; we reformed it to death. For decades, well-meaning political reformers have attacked intermediaries as corrupt, undemocratic, unnecessary, or (usually) all of the above. Americans have been busy demonizing and disempowering political professionals and parties, which is like spending decades abusing and attacking your own immune system. Eventually, you will get sick.

The disorder has other causes, too: developments such as ideological polarization, the rise of social media, and the radicalization of the Republican base. But chaos syndrome compounds the effects of those developments, by impeding the task of organizing to counteract them. Insurgencies in presidential races and on Capitol Hill are nothing new, and they are not necessarily bad, as long as the governing process can accommodate them. Years before the Senate had to cope with Ted Cruz, it had to cope with Jesse Helms. The difference is that Cruz shut down the government, which Helms could not have done had he even imagined trying.

Like many disorders, chaos syndrome is self-reinforcing. It causes governmental dysfunction, which fuels public anger, which incites political disruption, which causes yet more governmental dysfunction. Reversing the spiral will require understanding it. Consider, then, the etiology of a political disease: the immune system that defended the body politic for two centuries; the gradual dismantling of that immune system; the emergence of pathogens capable of exploiting the new vulnerability; the symptoms of the disorder; and, finally, its prognosis and treatment.

Immunity

Why the political class is a good thing

The Founders knew all too well about chaos. It was the condition that brought them together in 1787 under the Articles of Confederation. The central government had too few powers and powers of the wrong kinds, so they gave it more powers, and also multiple power centers. The core idea of the Constitution was to restrain ambition and excess by forcing competing powers and factions to bargain and compromise.

The Framers worried about demagogic excess and populist caprice, so they created buffers and gatekeepers between voters and the government. Only one chamber, the House of Representatives, would be directly elected. A radical who wanted to get into the Senate would need to get past the state legislature, which selected senators; a usurper who wanted to seize the presidency would need to get past the Electoral College, a convocation of elders who chose the president; and so on.

They were visionaries, those men in Philadelphia, but they could not foresee everything, and they made a serious omission. Unlike the British parliamentary system, the Constitution makes no provision for holding politicians accountable to one another. A rogue member of Congress can’t be “fired” by his party leaders, as a member of Parliament can; a renegade president cannot be evicted in a vote of no confidence, as a British prime minister can. By and large, American politicians are independent operators, and they became even more independent when later reforms, in the 19th and early 20th centuries, neutered the Electoral College and established direct election to the Senate.

The Constitution makes no mention of many of the essential political structures that we take for granted, such as political parties and congressional committees. If the Constitution were all we had, politicians would be incapable of getting organized to accomplish even routine tasks. Every day, for every bill or compromise, they would have to start from scratch, rounding up hundreds of individual politicians and answering to thousands of squabbling constituencies and millions of voters. By itself, the Constitution is a recipe for chaos.

So Americans developed a second, unwritten constitution. Beginning in the 1790s, politicians sorted themselves into parties. In the 1830s, under Andrew Jackson and Martin Van Buren, the parties established patronage machines and grass-roots bases. The machines and parties used rewards and the occasional punishment to encourage politicians to work together. Meanwhile, Congress developed its seniority and committee systems, rewarding reliability and establishing cooperative routines. Parties, leaders, machines, and congressional hierarchies built densely woven incentive structures that bound politicians into coherent teams. Personal alliances, financial contributions, promotions and prestige, political perks, pork-barrel spending, endorsements, and sometimes a trip to the woodshed or the wilderness: All of those incentives and others, including some of dubious respectability, came into play. If the Constitution was the system’s DNA, the parties and machines and political brokers were its RNA, translating the Founders’ bare-bones framework into dynamic organizations and thus converting conflict into action.

The informal constitution’s intermediaries have many names and faces: state and national party committees, county party chairs, congressional subcommittees, leadership pacs, convention delegates, bundlers, and countless more. For purposes of this essay, I’ll call them all middlemen, because all of them mediated between disorganized swarms of politicians and disorganized swarms of voters, thereby performing the indispensable task that the great political scientist James Q. Wilson called “assembling power in the formal government.”

The middlemen could be undemocratic, high-handed, devious, secretive. But they had one great virtue: They brought order from chaos. They encouraged coordination, interdependency, and mutual accountability. They discouraged solipsistic and antisocial political behavior. A loyal, time-serving member of Congress could expect easy renomination, financial help, promotion through the ranks of committees and leadership jobs, and a new airport or research center for his district. A turncoat or troublemaker, by contrast, could expect to encounter ostracism, marginalization, and difficulties with fund-raising. The system was hierarchical, but it was not authoritarian. Even the lowliest precinct walker or officeholder had a role and a voice and could expect a reward for loyalty; even the highest party boss had to cater to multiple constituencies and fend off periodic challengers.

Parties, machines, and hacks may not have been pretty, but at their best they did their job so well that the country forgot why it needed them. Politics seemed almost to organize itself, but only because the middlemen recruited and nurtured political talent, vetted candidates for competence and loyalty, gathered and dispensed money, built bases of donors and supporters, forged coalitions, bought off antagonists, mediated disputes, brokered compromises, and greased the skids to turn those compromises into law. Though sometimes arrogant, middlemen were not generally elitist. They excelled at organizing and representing unsophisticated voters, as Tammany Hall famously did for the working-class Irish of New York, to the horror of many Progressives who viewed the Irish working class as unfit to govern or even to vote.

The old machines were inclusive only by the standards of their day, of course. They were bad on race—but then, so were Progressives such as Woodrow Wilson. The more intrinsic hazard with middlemen and machines is the ever-present potential for corruption, which is a real problem. On the other hand, overreacting to the threat of corruption by stamping out influence-peddling (as distinct from bribery and extortion) is just as harmful. Political contributions, for example, look unseemly, but they play a vital role as political bonding agents. When a party raised a soft-money donation from a millionaire and used it to support a candidate’s campaign (a common practice until the 2002 McCain-Feingold law banned it in federal elections), the exchange of favors tied a knot of mutual accountability that linked candidate, party, and donor together and forced each to think about the interests of the others. Such transactions may not have comported with the Platonic ideal of democracy, but in the real world they did much to stabilize the system and discourage selfish behavior.

Middlemen have a characteristic that is essential in politics: They stick around. Because careerists and hacks make their living off the system, they have a stake in assembling durable coalitions, in retaining power over time, and in keeping the government in functioning order. Slash-and-burn protests and quixotic ideological crusades are luxuries they can’t afford. Insurgents and renegades have a role, which is to jolt the system with new energy and ideas; but professionals also have a role, which is to safely absorb the energy that insurgents unleash. Think of them as analogous to antibodies and white blood cells, establishing and patrolling the barriers between the body politic and would-be hijackers on the outside. As with biology, so with politics: When the immune system works, it is largely invisible. Only when it breaks down do we become aware of its importance.

Vulnerability

How the war on middlemen left America defenseless

Beginning early in the 20th century, and continuing right up to the present, reformers and the public turned against every aspect of insider politics: professional politicians, closed-door negotiations, personal favors, party bosses, financial ties, all of it. Progressives accused middlemen of subverting the public interest; populists accused them of obstructing the people’s will; conservatives accused them of protecting and expanding big government.

To some extent, the reformers were right. They had good intentions and valid complaints. Back in the 1970s, as a teenager in the post-Watergate era, I was on their side. Why allow politicians ever to meet behind closed doors? Sunshine is the best disinfectant! Why allow private money to buy favors and distort policy making? Ban it and use Treasury funds to finance elections! It was easy, in those days, to see that there was dirty water in the tub. What was not so evident was the reason the water was dirty, which was the baby. So we started reforming.

We reformed the nominating process. The use of primary elections instead of conventions, caucuses, and other insider-dominated processes dates to the era of Theodore Roosevelt, but primary elections and party influence coexisted through the 1960s; especially in congressional and state races, party leaders had many ways to influence nominations and vet candidates. According to Jon Meacham, in his biography of George H. W. Bush, here is how Bush’s father, Prescott Bush, got started in politics: “Samuel F. Pryor, a top Pan Am executive and a mover in Connecticut politics, called Prescott to ask whether Bush might like to run for Congress. ‘If you would,’ Pryor said, ‘I think we can assure you that you’ll be the nominee.’ ” Today, party insiders can still jawbone a little bit, but, as the 2016 presidential race has made all too clear, there is startlingly little they can do to influence the nominating process.

Primary races now tend to be dominated by highly motivated extremists and interest groups, with the perverse result of leaving moderates and broader, less well-organized constituencies underrepresented. According to the Pew Research Center, in the first 12 presidential-primary contests of 2016, only 17 percent of eligible voters participated in Republican primaries, and only 12 percent in Democratic primaries. In other words, Donald Trump seized the lead in the primary process by winning a mere plurality of a mere fraction of the electorate. In off-year congressional primaries, when turnout is even lower, it’s even easier for the tail to wag the dog. In the 2010 Delaware Senate race, Christine “I am not a witch” O’Donnell secured the Republican nomination by winning just a sixth of the state’s registered Republicans, thereby handing a competitive seat to the Democrats. Surveying congressional primaries for a 2014 Brookings Institution report, the journalists Jill Lawrence and Walter Shapiro observed: “The universe of those who actually cast primary ballots is small and hyper-partisan, and rewards candidates who hew to ideological orthodoxy.” By contrast, party hacks tend to shop for candidates who exert broad appeal in a general election and who will sustain and build the party’s brand, so they generally lean toward relative moderates and team players.

Moreover, recent research by the political scientists Jamie L. Carson and Jason M. Roberts finds that party leaders of yore did a better job of encouraging qualified mainstream candidates to challenge incumbents. “In congressional districts across the country, party leaders were able to carefully select candidates who would contribute to the collective good of the ticket,” Carson and Roberts write in their 2013 book, Ambition, Competition, and Electoral Reform: The Politics of Congressional Elections Across Time. “This led to a plentiful supply of quality candidates willing to enter races, since the potential costs of running and losing were largely underwritten by the party organization.” The switch to direct primaries, in which contenders generally self-recruit and succeed or fail on their own account, has produced more oddball and extreme challengers and thereby made general elections less competitive. “A series of reforms that were intended to create more open and less ‘insider’ dominated elections actually produced more entrenched politicians,” Carson and Roberts write. The paradoxical result is that members of Congress today are simultaneously less responsive to mainstream interests and harder to dislodge.

Was the switch to direct public nomination a net benefit or drawback? The answer to that question is subjective. But one effect is not in doubt: Institutionalists have less power than ever before to protect loyalists who play well with other politicians, or who take a tough congressional vote for the team, or who dare to cross single-issue voters and interests; and they have little capacity to fend off insurgents who owe nothing to anybody. Walled safely inside their gerrymandered districts, incumbents are insulated from general-election challenges that might pull them toward the political center, but they are perpetually vulnerable to primary challenges from extremists who pull them toward the fringes. Everyone worries about being the next Eric Cantor, the Republican House majority leader who, in a shocking upset, lost to an unknown Tea Partier in his 2014 primary. Legislators are scared of voting for anything that might increase the odds of a primary challenge, which is one reason it is so hard to raise the debt limit or pass a budget.

In March, when Republican Senator Jerry Moran of Kansas told a Rotary Club meeting that he thought President Obama’s Supreme Court nominee deserved a Senate hearing, the Tea Party Patriots immediately responded with what has become activists’ go-to threat: “It’s this kind of outrageous behavior that leads Tea Party Patriots Citizens Fund activists and supporters to think seriously about encouraging Dr. Milton Wolf”—a physician and Tea Party activist—“to run against Sen. Moran in the August GOP primary.” (Moran hastened to issue a statement saying that he would oppose Obama’s nominee regardless.) Purist issue groups often have the whip hand now, and unlike the elected bosses of yore, they are accountable only to themselves and are able merely to prevent legislative action, not to organize it.

We reformed political money. Starting in the 1970s, large-dollar donations to candidates and parties were subject to a tightening web of regulations. The idea was to reduce corruption (or its appearance) and curtail the power of special interests—certainly laudable goals. Campaign-finance rules did stop some egregious transactions, but at a cost: Instead of eliminating money from politics (which is impossible), the rules diverted much of it to private channels. Whereas the parties themselves were once largely responsible for raising and spending political money, in their place has arisen a burgeoning ecology of deep-pocketed donors, super pacs, 501(c)(4)s, and so-called 527 groups that now spend hundreds of millions of dollars each cycle. The result has been the creation of an array of private political machines across the country: for instance, the Koch brothers’ Americans for Prosperity and Karl Rove’s American Crossroads on the right, and Tom Steyer’s NextGen Climate on the left.

Private groups are much harder to regulate, less transparent, and less accountable than are the parties and candidates, who do, at the end of the day, have to face the voters. Because they thrive on purism, protest, and parochialism, the outside groups are driving politics toward polarization, extremism, and short-term gain. “You may win or lose, but at least you have been intellectually consistent—your principles haven’t been defeated,” an official with Americans for Prosperity told The Economist in October 2014. The parties, despite being called to judgment by voters for their performance, face all kinds of constraints and regulations that the private groups don’t, tilting the playing field against them. “The internal conversation we’ve been having is ‘How do we keep state parties alive?’ ” the director of a mountain-state Democratic Party organization told me and Raymond J. La Raja recently for a Brookings Institution report. Republicans told us the same story. “We believe we are fighting for our lives in the current legal and judicial framework, and the super pacs and (c)(4)s really present a direct threat to the state parties’ existence,” a southern state’s Republican Party director said.

The state parties also told us they can’t begin to match the advertising money flowing from outside groups and candidates. Weakened by regulations and resource constraints, they have been reduced to spectators, while candidates and groups form circular firing squads and alienate voters. At the national level, the situation is even more chaotic—and ripe for exploitation by a savvy demagogue who can make himself heard above the din, as Donald Trump has so shrewdly proved.

We reformed Congress. For a long time, seniority ruled on Capitol Hill. To exercise power, you had to wait for years, and chairs ran their committees like fiefs. It was an arrangement that hardly seemed either meritocratic or democratic. Starting with a rebellion by the liberal post-Watergate class in the ’70s, and then accelerating with the rise of Newt Gingrich and his conservative revolutionaries in the ’90s, the seniority and committee systems came under attack and withered. Power on the Hill has flowed both up to a few top leaders and down to individual members. Unfortunately, the reformers overlooked something important: Seniority and committee spots rewarded teamwork and loyalty, they ensured that people at the top were experienced, and they harnessed hundreds of middle-ranking members of Congress to the tasks of legislating. Compounding the problem, Gingrich’s Republican revolutionaries, eager to prove their anti-Washington bona fides, cut committee staffs by a third, further diminishing Congress’s institutional horsepower.

Congress’s attempts to replace hierarchies and middlemen with top-down diktat and ad hoc working groups have mostly failed. More than perhaps ever before, Congress today is a collection of individual entrepreneurs and pressure groups. In the House, disintermediation has shifted the balance of power toward a small but cohesive minority of conservative Freedom Caucus members who think nothing of wielding their power against their own leaders. Last year, as House Republicans struggled to agree on a new speaker, the conservatives did not blush at demanding “the right to oppose their leaders and vote down legislation without repercussions,” as Time magazine reported. In the Senate, Ted Cruz made himself a leading presidential contender by engaging in debt-limit brinkmanship and deriding the party’s leadership, going so far as to call Majority Leader Mitch McConnell a liar on the Senate floor. “The rhetoric—and confrontational stance—are classic Cruz,” wrote Burgess Everett in Politico last October: “Stake out a position to the right of where his leaders will end up, criticize them for ignoring him and conservative grass-roots voters, then use the ensuing internecine fight to stoke his presidential bid.” No wonder his colleagues detest him. But Cruz was doing what makes sense in an age of maximal political individualism, and we can safely bet that his success will inspire imitation.

We reformed closed-door negotiations. As recently as the early 1970s, congressional committees could easily retreat behind closed doors and members could vote on many bills anonymously, with only the final tallies reported. Federal advisory committees, too, could meet off the record. Understandably, in the wake of Watergate, those practices came to be viewed as suspect. Today, federal law, congressional rules, and public expectations have placed almost all formal deliberations and many informal ones in full public view. One result is greater transparency, which is good. But another result is that finding space for delicate negotiations and candid deliberations can be difficult. Smoke-filled rooms, whatever their disadvantages, were good for brokering complex compromises in which nothing was settled until everything was settled; once gone, they turned out to be difficult to replace. In public, interest groups and grandstanding politicians can tear apart a compromise before it is halfway settled.

Despite promising to televise negotiations over health-care reform, President Obama went behind closed doors with interest groups to put the package together; no sane person would have negotiated in full public view. In 2013, Congress succeeded in approving a modest bipartisan budget deal in large measure because the House and Senate Budget Committee chairs were empowered to “figure it out themselves, very, very privately,” as one Democratic aide told Jill Lawrence for a 2015 Brookings report. TV cameras, recorded votes, and public markups do increase transparency, but they come at the cost of complicating candid conversations. “The idea that Washington would work better if there were TV cameras monitoring every conversation gets it exactly wrong,” the Democratic former Senate majority leader Tom Daschle wrote in 2014, in his foreword to the book City of Rivals. “The lack of opportunities for honest dialogue and creative give-and-take lies at the root of today’s dysfunction.”

We reformed pork. For most of American history, a principal goal of any member of Congress was to bring home bacon for his district. Pork-barrel spending never really cost very much, and it helped glue Congress together by giving members a kind of currency to trade: You support my pork, and I’ll support yours. Also, because pork was dispensed by powerful appropriations committees with input from senior congressional leaders, it provided a handy way for the leadership to buy votes and reward loyalists. Starting in the ’70s, however, and then snowballing in the ’90s, the regular appropriations process broke down, a casualty of reforms that weakened appropriators’ power, of “sunshine laws” that reduced their autonomy, and of polarization that complicated negotiations. Conservatives and liberals alike attacked pork-barreling as corrupt, culminating in early 2011, when a strange-bedfellows coalition of Tea Partiers and progressives banned earmarking, the practice of dropping goodies into bills as a way to attract votes—including, ironically, votes for politically painful spending reductions.

Congress has not passed all its annual appropriations bills in 20 years, and more than $300 billion a year in federal spending goes out the door without proper authorization. Routine business such as passing a farm bill or a surface-transportation bill now takes years instead of weeks or months to complete. Today two-thirds of federal-program spending (excluding interest on the national debt) runs on formula-driven autopilot. This automatic spending by so-called entitlement programs eludes the discipline of being regularly voted on, dwarfs old-fashioned pork in magnitude, and is so hard to restrain that it’s often called the “third rail” of politics. The political cost has also been high: Congressional leaders lost one of their last remaining tools to induce followership and team play. “Trying to be a leader where you have no sticks and very few carrots is dang near impossible,” the Republican former Senate Majority Leader Trent Lott told CNN in 2013, shortly after renegade Republicans pointlessly shut down the government. “Members don’t get anything from you and leaders don’t give anything. They don’t feel like you can reward them or punish them.”

Like campaign contributions and smoke-filled rooms, pork is a tool of democratic governance, not a violation of it. It can be used for corrupt purposes but also, very often, for vital ones. As the political scientist Diana Evans wrote in a 2004 book, Greasing the Wheels: Using Pork Barrel Projects to Build Majority Coalitions in Congress, “The irony is this: pork barreling, despite its much maligned status, gets things done.” In 1964, to cite one famous example, Lyndon Johnson could not have passed his landmark civil-rights bill without support from House Republican leader Charles Halleck of Indiana, who named his price: a nasa research grant for his district, which LBJ was glad to provide. Just last year, Republican Senator John McCain, the chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee, was asked how his committee managed to pass bipartisan authorization bills year after year, even as the rest of Congress ground to a legislative standstill. In part, McCain explained, it was because “there’s a lot in there for members of the committees.”

Party-dominated nominating processes, soft money, congressional seniority, closed-door negotiations, pork-barrel spending—put each practice under a microscope in isolation, and it seems an unsavory way of doing political business. But sweep them all away, and one finds that business is not getting done at all. The political reforms of the past 40 or so years have pushed toward disintermediation—by favoring amateurs and outsiders over professionals and insiders; by privileging populism and self-expression over mediation and mutual restraint; by stripping middlemen of tools they need to organize the political system. All of the reforms promote an individualistic, atomized model of politics in which there are candidates and there are voters, but there is nothing in between. Other, larger trends, to be sure, have also contributed to political disorganization, but the war on middlemen has amplified and accelerated them.

Pathogens

Donald Trump and other viruses

By the beginning of this decade, the political system’s organic defenses against outsiders and insurgents were visibly crumbling. All that was needed was for the right virus to come along and exploit the opening. As it happened, two came along.

In 2009, on the heels of President Obama’s election and the economic-bailout packages, angry fiscal conservatives launched the Tea Party insurgency and watched, somewhat to their own astonishment, as it swept the country. Tea Partiers shared some of the policy predilections of loyal Republican partisans, but their mind-set was angrily anti-establishment. In a 2013 Pew Research poll, more than 70 percent of them disapproved of Republican leaders in Congress. In a 2010 Pew poll, they had rejected compromise by similar margins. They thought nothing of mounting primary challenges against Republican incumbents, and they made a special point of targeting Republicans who compromised with Democrats or even with Republican leaders. In Congress, the Republican House leadership soon found itself facing a GOP caucus whose members were too worried about “getting primaried” to vote for the compromises necessary to govern—or even to keep the government open. Threats from the Tea Party and other purist factions often outweigh any blandishments or protection that leaders can offer.

So far the Democrats have been mostly spared the anti-compromise insurrection, but their defenses are not much stronger. Molly Ball recently reported for The Atlantic’s Web site on the Working Families Party, whose purpose is “to make Democratic politicians more accountable to their liberal base through the asymmetric warfare party primaries enable, much as the conservative movement has done to Republicans.” Because African Americans and union members still mostly behave like party loyalists, and because the Democratic base does not want to see President Obama fail, the Tea Party trick hasn’t yet worked on the left. But the Democrats are vulnerable structurally, and the anti-compromise virus is out there.

A second virus was initially identified in 2002, by the University of Nebraska at Lincoln political scientists John R. Hibbing and Elizabeth Theiss-Morse, in their book Stealth Democracy: Americans’ Beliefs About How Government Should Work. It’s a shocking book, one whose implications other scholars were understandably reluctant to engage with. The rise of Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders, however, makes confronting its thesis unavoidable.

Using polls and focus groups, Hibbing and Theiss-Morse found that between 25 and 40 percent of Americans (depending on how one measures) have a severely distorted view of how government and politics are supposed to work. I think of these people as “politiphobes,” because they see the contentious give-and-take of politics as unnecessary and distasteful. Specifically, they believe that obvious, commonsense solutions to the country’s problems are out there for the plucking. The reason these obvious solutions are not enacted is that politicians are corrupt, or self-interested, or addicted to unnecessary partisan feuding. Not surprisingly, politiphobes think the obvious, commonsense solutions are the sorts of solutions that they themselves prefer. But the more important point is that they do not acknowledge that meaningful policy disagreement even exists. From that premise, they conclude that all the arguing and partisanship and horse-trading that go on in American politics are entirely unnecessary. Politicians could easily solve all our problems if they would only set aside their craven personal agendas.

If politicians won’t do the job, then who will? Politiphobes, according to Hibbing and Theiss-Morse, believe policy should be made not by messy political conflict and negotiations but by ensids: empathetic, non-self-interested decision makers. These are leaders who will step forward, cast aside cowardly politicians and venal special interests, and implement long-overdue solutions. ensids can be politicians, technocrats, or autocrats—whatever works. Whether the process is democratic is not particularly important.

Chances are that politiphobes have been out there since long before Hibbing and Theiss-Morse identified them in 2002. Unlike the Tea Party or the Working Families Party, they aren’t particularly ideological: They have popped up left, right, and center. Ross Perot’s independent presidential candidacies of 1992 and 1996 appealed to the idea that any sensible businessman could knock heads together and fix Washington. In 2008, Barack Obama pandered to a center-left version of the same fantasy, promising to magically transcend partisan politics and implement the best solutions from both parties.

No previous outbreak, however, compares with the latest one, which draws unprecedented virulence from two developments. One is a steep rise in antipolitical sentiment, especially on the right. According to polling by Pew, from 2007 to early 2016 the percentage of Americans saying they would be less likely to vote for a presidential candidate who had been an elected official in Washington for many years than for an outsider candidate more than doubled, from 15 percent to 31 percent. Republican opinion has shifted more sharply still: The percentage of Republicans preferring “new ideas and a different approach” over “experience and a proven record” almost doubled in just the six months from March to September of 2015.

The other development, of course, was Donald Trump, the perfect vector to concentrate politiphobic sentiment, intensify it, and inject it into presidential politics. He had too much money and free media to be spent out of the race. He had no political record to defend. He had no political debts or party loyalty. He had no compunctions. There was nothing to restrain him from sounding every note of the politiphobic fantasy with perfect pitch.

Democrats have not been immune, either. Like Trump, Bernie Sanders appealed to the antipolitical idea that the mere act of voting for him would prompt a “revolution” that would somehow clear up such knotty problems as health-care coverage, financial reform, and money in politics. Like Trump, he was a self-sufficient outsider without customary political debts or party loyalty. Like Trump, he neither acknowledged nor cared—because his supporters neither acknowledged nor cared—that his plans for governing were delusional.

Trump, Sanders, and Ted Cruz have in common that they are political sociopaths—meaning not that they are crazy, but that they don’t care what other politicians think about their behavior and they don’t need to care. That three of the four final presidential contenders in 2016 were political sociopaths is a sign of how far chaos syndrome has gone. The old, mediated system selected such people out. The new, disintermediated system seems to be selecting them in.

Symptoms

The disorder that exacerbates all other disorders

There is nothing new about political insurgencies in the United States—nor anything inherently wrong with them. Just the opposite, in fact: Insurgencies have brought fresh ideas and renewed participation to the political system since at least the time of Andrew Jackson.

There is also nothing new about insiders losing control of the presidential nominating process. In 1964 and 1972, to the dismay of party regulars, nominations went to unelectable candidates—Barry Goldwater for the Republicans in 1964 and George McGovern for the Democrats in 1972—who thrilled the parties’ activist bases and went on to predictably epic defeats. So it’s tempting to say, “Democracy is messy. Insurgents have fair gripes. Incumbents should be challenged. Who are you, Mr. Establishment, to say the system is broken merely because you don’t like the people it is pushing forward?”

The problem is not, however, that disruptions happen. The problem is that chaos syndrome wreaks havoc on the system’s ability to absorb and channel disruptions. Trying to quash political disruptions would probably only create more of them. The trick is to be able to govern through them.

Leave aside the fact that Goldwater and McGovern, although ideologues, were estimable figures within their parties. (McGovern actually co-chaired a Democratic Party commission that rewrote the nominating rules after 1968, opening the way for his own campaign.) Neither of them, either as senator or candidate, wanted to or did disrupt the ordinary workings of government.

Jason Grumet, the president of the Bipartisan Policy Center and the author of City of Rivals, likes to point out that within three weeks of Bill Clinton’s impeachment by the House of Representatives, the president was signing new laws again. “While they were impeaching him they were negotiating, they were talking, they were having committee hearings,” Grumet said in a recent speech. “And so we have to ask ourselves, what is it that not long ago allowed our government to metabolize the aggression that is inherent in any pluralistic society and still get things done?”

I have been covering Washington since the early 1980s, and I’ve seen a lot of gridlock. Sometimes I’ve been grateful for gridlock, which is an appropriate outcome when there is no working majority for a particular policy. For me, however, 2011 brought a wake-up call. The system was failing even when there was a working majority. That year, President Obama and Republican House Speaker John Boehner, in intense personal negotiations, tried to clinch a budget agreement that touched both parties’ sacred cows, curtailing growth in the major entitlement programs such as Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security by hundreds of billions of dollars and increasing revenues by $800 billion or more over 10 years, as well as reducing defense and nondefense discretionary spending by more than $1 trillion. Though it was less grand than previous budgetary “grand bargains,” the package represented the kind of bipartisan accommodation that constitutes the federal government’s best and perhaps only path to long-term fiscal stability.

People still debate why the package fell apart, and there is blame enough to go around. My own reading at the time, however, concurred with Matt Bai’s postmortem in The New York Times: Democratic leaders could have found the rank-and-file support they needed to pass the bargain, but Boehner could not get the deal past conservatives in his own caucus. “What’s undeniable, despite all the furious efforts to peddle a different story,” Bai wrote, “is that Obama managed to persuade his closest allies to sign off on what he wanted them to do, and Boehner didn’t, or couldn’t.” We’ll never know, but I believe that the kind of budget compromise Boehner and Obama tried to shake hands on, had it reached a vote, would have passed with solid majorities in both chambers and been signed into law. The problem was not polarization; it was disorganization. A latent majority could not muster and assert itself.

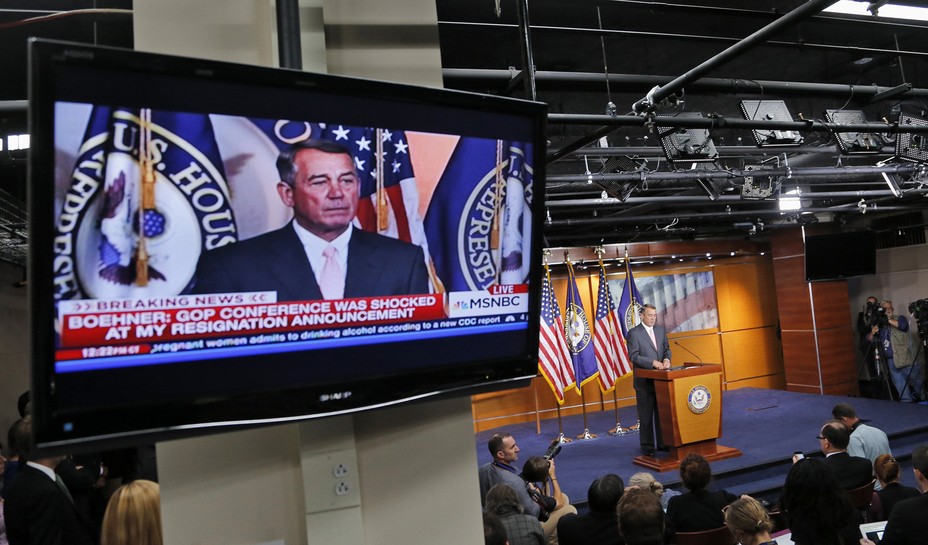

As soon became apparent, Boehner’s 2011 debacle was not a glitch but part of an emerging pattern. Two years later, the House’s conservative faction shut down the government with the connivance of Ted Cruz, the very last thing most Republicans wanted to happen. When Boehner was asked by Jay Leno why he had permitted what the speaker himself called a “very predictable disaster,” he replied, rather poignantly: “When I looked up, I saw my colleagues going this way. You learn that a leader without followers is simply a man taking a walk.”

Boehner was right. Washington doesn’t have a crisis of leadership; it has a crisis of followership. One can argue about particulars, and Congress does better on some occasions than on others. Overall, though, minority factions and veto groups are becoming ever more dominant on Capitol Hill as leaders watch their organizational capacity dribble away. Helpless to do much more than beg for support, and hostage to his own party’s far right, an exhausted Boehner finally gave up and quit last year. Almost immediately, his heir apparent, Majority Leader Kevin McCarthy, was shot to pieces too. No wonder Paul Ryan, in his first act as speaker, remonstrated with his own colleagues against chaos.

Nevertheless, by spring the new speaker was bogged down. “Almost six months into the job, Ryan and his top lieutenants face questions about whether the Wisconsin Republican’s tenure atop the House is any more effective than his predecessor,” Politico’s Web site reported in April. The House Republican Conference, an unnamed Republican told Politico, is “unwhippable and unleadable. Ryan is as talented as you can be: There’s nobody better. But even he can’t do anything. Who could?”

Of course, Congress’s incompetence makes the electorate even more disgusted, which leads to even greater political volatility. In a Republican presidential debate in March, Ohio Governor John Kasich described the cycle this way: The people, he said, “want change, and they keep putting outsiders in to bring about the change. Then the change doesn’t come … because we’re putting people in that don’t understand compromise.” Disruption in politics and dysfunction in government reinforce each other. Chaos becomes the new normal.

Being a disorder of the immune system, chaos syndrome magnifies other problems, turning political head colds into pneumonia. Take polarization. Over the past few decades, the public has become sharply divided across partisan and ideological lines. Chaos syndrome compounds the problem, because even when Republicans and Democrats do find something to work together on, the threat of an extremist primary challenge funded by a flood of outside money makes them think twice—or not at all. Opportunities to make bipartisan legislative advances slip away.

Or take the new technologies that are revolutionizing the media. Today, a figure like Trump can reach millions through Twitter without needing to pass network‑TV gatekeepers or spend a dime. A figure like Sanders can use the Internet to reach millions of donors without recourse to traditional fund-raising sources. Outside groups, friendly and unfriendly alike, can drown out political candidates in their own races. (As a frustrated Cruz told a supporter about outside groups ostensibly backing his presidential campaign, “I’m left to just hope that what they say bears some resemblance to what I actually believe.”) Disruptive media technologies are nothing new in American politics; they have arisen periodically since the early 19th century, as the historian Jill Lepore noted in a February article in The New Yorker. What is new is the system’s difficulty in coping with them. Disintermediating technologies bring fresh voices into the fray, but they also bring atomization and cacophony. To organize coherent plays amid swarms of attack ads, middlemen need to be able to coordinate the fund-raising and messaging of candidates and parties and activists—which is what they are increasingly hard-pressed to do.

Assembling power to govern a sprawling, diverse, and increasingly divided democracy is inevitably hard. Chaos syndrome makes it all the harder. For Democrats, the disorder is merely chronic; for the Republican Party, it is acute. Finding no precedent for what he called Trump’s hijacking of an entire political party, Jon Meacham went so far as to tell Joe Scarborough in The Washington Post that George W. Bush might prove to be the last Republican president.

Nearly everyone panned party regulars for not stopping Trump much earlier, but no one explained just how the party regulars were supposed to have done that. Stopping an insurgency requires organizing a coalition against it, but an incapacity to organize is the whole problem. The reality is that the levers and buttons parties and political professionals might once have pulled and pushed had long since been disconnected.

Prognosis and Treatment

Chaos syndrome as a psychiatric disorder

I don’t have a quick solution to the current mess, but I do think it would be easy, in principle, to start moving in a better direction. Although returning parties and middlemen to anything like their 19th-century glory is not conceivable—or, in today’s America, even desirable—strengthening parties and middlemen is very doable. Restrictions inhibiting the parties from coordinating with their own candidates serve to encourage political wildcatting, so repeal them. Limits on donations to the parties drive money to unaccountable outsiders, so lift them. Restoring the earmarks that help grease legislative success requires nothing more than a change in congressional rules. And there are all kinds of ways the parties could move insiders back to the center of the nomination process. If they wanted to, they could require would-be candidates to get petition signatures from elected officials and county party chairs, or they could send unbound delegates to their conventions (as several state parties are doing this year), or they could enhance the role of middlemen in a host of other ways.

Building party machines and political networks is what career politicians naturally do, if they’re allowed to do it. So let them. I’m not talking about rigging the system to exclude challengers or prevent insurgencies. I’m talking about de-rigging the system to reduce its pervasive bias against middlemen. Then they can do their job, thereby making the world safe for challengers and insurgencies.

Unfortunately, although the mechanics of de-rigging are fairly straightforward, the politics of it are hard. The public is wedded to an anti-establishment narrative. The political-reform community is invested in direct participation, transparency, fund-raising limits on parties, and other elements of the anti-intermediation worldview. The establishment, to the extent that there still is such a thing, is demoralized and shattered, barely able to muster an argument for its own existence.

But there are optimistic signs, too. Liberals in the campaign-finance-reform community are showing new interest in strengthening the parties. Academics and commentators are getting a good look at politics without effective organizers and cohesive organizations, and they are terrified. On Capitol Hill, conservatives and liberals alike are on board with restoring regular order in Congress. In Washington, insiders have had some success at reorganizing and pushing back. No Senate Republican was defeated by a primary challenger in 2014, in part because then–Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, a machine politician par excellence, created a network of business allies to counterpunch against the Tea Party.

The biggest obstacle, I think, is the general public’s reflexive, unreasoning hostility to politicians and the process of politics. Neurotic hatred of the political class is the country’s last universally acceptable form of bigotry. Because that problem is mental, not mechanical, it really is hard to remedy.

In March, a Trump supporter told The New York Times, “I want to see Trump go up there and do damage to the Republican Party.” Another said, “We know who Donald Trump is, and we’re going to use Donald Trump to either take over the G.O.P. or blow it up.” That kind of anti-establishment nihilism deserves no respect or accommodation in American public life. Populism, individualism, and a skeptical attitude toward politics are all healthy up to a point, but America has passed that point. Political professionals and parties have many shortcomings to answer for—including, primarily on the Republican side, their self-mutilating embrace of anti-establishment rhetoric—but relentlessly bashing them is no solution. You haven’t heard anyone say this, but it’s time someone did: Our most pressing political problem today is that the country abandoned the establishment, not the other way around.