Which is it? Are we witnessing the death of Labour, as Tony Blair warned this week? Or is it the party’s rebirth, as Jeremy Corbyn’s followers hope? The truth, as ever, will lie somewhere in between. Something will die, or at least be placed on life-support, if Corbyn wins – the prospect of Labour as a single-party alternative government. That’s a historic change. But Labour will survive in some form if Corbyn wins. A significant number of people will go on voting for it, some with enthusiasm. It will be a strange sort of death.

When Labour lost the general election, the phrase “the strange death of Labour Britain” surfaced in several postmortems. Readers of a certain age who have studied 20th-century British political history will know where the phrase comes from. It comes from George Dangerfield’s 1935 book The Strange Death of Liberal England, which traced the astonishingly rapid collapse of the party and culture that appeared to command the country just before the first world war.

Dangerfield’s thesis was that the death of the Liberals was not, as many of his era suggested, the result of the first world war. He argued instead that Liberal England was already decaying before the war under the impact of large political and social changes to which the Liberal party had no effective or adaptive answer. Its landslide win in 1906 was a victory, he argued, from which the Liberals never recovered.

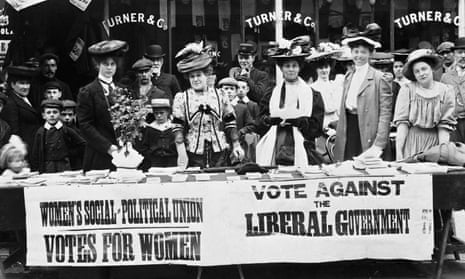

Dangerfield identified three such changes in particular: Ireland, where the Liberals were powerless to prevent violence and revolt; the rise of the labour movement, whose interests the Liberals could not bring themselves to embrace adequately; and votes for women, a radical demand for equality over which the Liberal party fatally hesitated.

Over the years, Dangerfield’s book became a classic. As politics moved through the 20th century, a variety of “strange death” theories emerged in echo of Dangerfield. In 1968 the philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre wrote about the strange death of social democratic England. In 1993, the historian Kevin Jeffreys marked the strange death of Labour England. In 2005, it was the turn of the Conservatives, with Geoffrey Wheatcroft obituarising the strange death of Tory England. In 2012 Gerry Hassan and Eric Shaw wrote of the strange death of Labour Scotland.

It is tempting to say that these efforts were all open to the charge that they were clever titles in search of a convincing thesis. Dangerfield, after all, had the advantage that the death of which he wrote was not in question. Liberal England had indeed died by 1935, whereas there was vigorous life in Labour England and Tory England after they were obituarised.

It is still not self-evident, even in 2015, that Labour Britain – or Labour England, and perhaps even Labour Scotland – can be pronounced dead and buried. Labour’s more grisly fate may be to survive, not perish. Its condition under and post-Corbyn could just as easily be a kind of living death, with the party retaining enough core working-class and Guardianista loyalties in various parts of the country to remain a factor, yet never doing well enough to challenge the Conservatives or badly enough to decide to head for the political Dignitas clinic.

After the general election, I went back to my dog-eared copy of Dangerfield and re-read it. The parallels between Labour’s situation and the fate of the Liberals were far more striking than the disjunctions. To pick just one, Labour’s great victory in 1997 now increasingly looks like what Dangerfield saw in the Liberal landslide of 1906 – a victory from which the party never recovered.

But there is also an echo in the central thesis. It wasn’t the war, wrote Dangerfield, that killed the Liberals, it was what was already happening before the war. That could be true of the modern Labour party too. Lots of people talk as if Iraq was the watershed moment, the sin that marked New Labour’s fall. But, as with the Liberals in 1914, Labour in 2003 was already losing its support and its grip for a lot of other reasons.

Those other reasons are themselves foreshadowed in Dangerfield’s account. The first was Ireland and the future of the union. Asquith’s government bottled it on Ireland and thus handed the initiative to the nationalists. Labour’s handling of Scotland has echoed the Liberals’ handling of Ireland, giving the initiative to the nationalists. Labour’s early-21st-century vision of a devolved union has proved as unstable as the Liberals’ early-20th-century vision of a home rule-based union, with the additional problem that the success of the SNP has helped to unleash Corbynism as a serious force.

The second issue is the labour movement, whose growing power and demands the Liberals could not embrace a century ago. A Labour party explicitly bound to the labour movement’s interests was the result. Yet today Labour remains bound to a labour movement in historic decline. Just as the Liberals in the last century were unable to embrace labour, so the Labour party today is unable to free itself. In post-industrial Britain, the embrace is fatal. It makes that kind of Labour party a minority party, as a Corbyn-led party is likely to find.

Then there’s the third issue that broke the Liberals – women’s rights. I admit that this could wreck my theory about Dangerfield’s modern pertinence. Labour, after all, is a party of women’s rights. But if we reframe the suffragette challenge as an essentially democratic, rather than a gender, issue, the parallel is much clearer. Labour does not do modern democracy. Labour won’t reform the voting system, won’t revive local government, won’t abolish the House of Lords, won’t energise industrial and corporate democracy and won’t revive its own internal party democracy either. It is a top-down party, much as the Asquith Liberal party was.

It would be too simplistic to say that Scottish nationalism, the decline of the labour movement and the failure to embrace democratic reforms are between them the only reasons why Labour today is struggling to be the national movement or the plausible alternative government that it once was. But they are undoubtedly three very strong examples of why Labour’s problems will not begin if Corbyn wins – though they will worsen – and did not begin when Blair invaded Iraq either.

The problems were there all along. They still are. The failure to resolve them is at the heart of the strange death of Labour Britain. It is an event that our generation is witnessing with a similar incredulity to that with which our forebears watched the death of Liberal England.