Champagne corks would have popped in the offices of EMI and Universal on Monday, when the EU ratified a new law – "Cliff's law", after Cliff Richard – that extended the copyright in music recordings from 50 years to 70 years. The wealth of British music from the 1960s, even now largely untapped by the major labels, will almost certainly remain in their grasp for another two decades.

Thirty years ago, the music industry complained home taping was killing music, and came up with a natty crossbones logo that scarred every album's inner sleeve for the next few years. Of course, it wasn't, and the industry was flush. Then, while milking the nascent CD market with expensive, poorly mastered reissues, the major labels splurged their huge profits on office extravagances and hugely expensive videos that, pre-YouTube, disappeared after a handful of views. Still the labels whined: "Please feel sorry for us."

Now the industry really is dying, or at least shape-shifting and shrinking. Having cried wolf once, it is hard to feel sympathetic. And so, it insisted the 50-year copyright term would have hurt the artists, not the record companies.

Paul McGuinness, manager of U2, wrote in the Daily Telegraph earlier this summer about "the systemic copyright infringement that has helped wipe out so many musicians, bands and labels in recent years". I can't think of a single artist or band who has split up or retired in protest at illegal downloading. Without changes to copyright laws, McGuinness asked: "Where is the investment going to come from to fund the next generation of bands such as U2 and Coldplay?" Fran Nevrkla, chairman of the music licensing body PPL, welcomed the EU ruling, saying the "enhanced copyright framework will enable the record companies, big and small, to continue investing in new recordings and new talent". Not everyone agreed. According to media and intellectual property lawyer Daniel Byrne, the royalty pot "will not get substantially larger", but "the available money will be split more ways (and now to more estates of deceased performers). This rewards unproductive performers and means there is less available to support younger acts."

When you hear Jools Holland claiming "artists put their hearts and souls into creating music, and it is only fair that they are recompensed in line with the rest of Europe – it's important that creators get paid for the work they do", you wonder if he has ever asked his accountant about Squeeze royalties, or never encountered a musician who has been screwed over by his label.

Maybe Jools should speak to Nic Jones. His 1980 album Penguin Eggs was voted second-best folk album of all time by listeners of Mike Harding's Radio 2 show. In 1982 Jones was almost killed in a car crash, and was so badly injured he has found it almost impossible to play the guitar or fiddle since. Income from his old albums would have been welcome but, because Jones doesn't own the recordings, he has received nothing. His first three albums were recorded for Bill Leader's Trailer label which, after it went bankrupt, was bought by a company called Celtic Music. Celtic Music's owner Dave Bulmer has sat on the entire Trailer catalogue – outside of Topic, the most significant British folk label of the 70s – with only the occasional record sneaking out. Why? He could be holding out for a folk revival during which he could sell the label on and make the proverbial killing. Whatever the reason, Jones could do with the income from reissues of his albums.

The copyright laws, as they stood, meant Jones's first two albums would have become public domain within 10 years time – at which point he could have reissued them himself. They would have belonged to the public. Instead, as part of the Trailer catalogue, they will stay in the hands of Dave Bulmer for another 30 years. It's hard to tally this with Nevrkla's claim that the change will benefit "the whole community of recording artists, orchestral players, session musicians, backing singers and other performers … which is so important, especially when those individuals reach ripe old age".

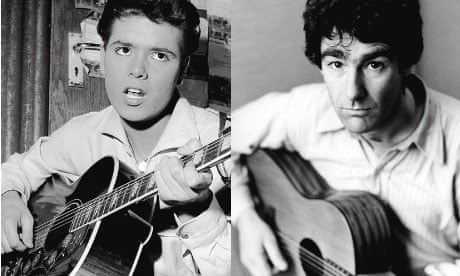

Pop stars of the late 50s and early 60s may have reached a ripe old age, but are often still in business. Take Craig Douglas, who racked up a string of top 10 hits, including a 1959 No 1, Only Sixteen. The "singing milkman" isn't used to having his hits used in car adverts or even getting much airplay, aside from the odd track on Radio 2's Sounds of the 60s. Instead, he is reliant on playing shows to people who were there at the time and remember the likes of Pretty Blue Eyes. As the copyright laws stood, Douglas would have been able to press CDs of his own hits and sell them at his shows without having to go through EMI, the record company that has owned them since they were recorded. If he only sold 10 a night, that could be £100 in his pocket. Compare that to the figures estimated by a group of economists, intellectual property experts and music academics who studied the effects of copyright term extension: "Consolidating the figures published in the annual reports of various collecting societies, our best estimate is that for the typical performing artist, the annual payout is in the lower hundreds of pounds and will not increase from extension … £250 a year is not a pension."

What really set the industry lobbying for term extensions was not the desire to do right by Craig Douglas or Nic Jones. It was the realisation that the single biggest revenue generator in British pop – the Beatles' catalogue – was about to start falling out of copyright. The EU ruling has been labelled "Cliff's law", but Paul McCartney pushed just as hard for it.

Of course, you can see Cliff and Macca's point – who would want to see their precious work repackaged cheaply and shoddily by fly-by-night companies? But the flipside of the public domain argument is that genuine enthusiasts can use out-of-copyright material to make extraordinary new compilations to the benefit of the listening public. One of the most exciting series of the last few years has been the British Hit Parade, an annual roundup of every single to make the UK charts since they began in 1952. Like BBC4's Top of the Pops reruns, this is history played back in real time; you can appreciate the true impact of Heartbreak Hotel as a new entry in 1956, sandwiched between Frankie Laine's Hell Hath No Fury and Don Robertson's The Happy Whistler. Given this context, it's much easier to understand why people really did think Little Richard sounded like an alien. Odd, forgotten crazes become apparent – not only things like the mambo (1954) or songs about babies (1953), but a string of cowboy hits in 1955, predating the UK's taste for something equally American but a little more visceral. Was 1960 really pop's worst-ever year, worse even than 1976? You can listen to the 12-disc 1960 British Hit Parade and decide for yourself. (Answer: yes it was.)

Expiring copyrights have also led to "lost" recordings being dug up by musical archeologists such as Jonny Trunk. Kenny Graham's Moondog and Suncat Suite was a 1958 tribute to the New York street musician Moondog, played by Graham, a British jazzer, and engineered by Joe Meek. It's other-worldly, quite beautiful and, in its initial vinyl pressing, extremely rare. "It's good for the whole industry, it's good for the economy to make it public and make it all available," Trunk says. "Half the time the majors don't want to release this stuff. The Kenny Graham album became public domain; no one released it. I did, then it gets on TV in an ad for Terry's Chocolate Orange – if I hadn't issued it, it would have remained hidden. Now with the money from the ad, Graham's daughter has the opportunity to leave work and become a gardener." MGM, Graham's original label, had the album in its possession for half a century and did nothing with it.

The real money for musicians remains, as ever, in publishing; you write the songs, you get paid whenever your song is played in public, and the copyright for composers already lasts for their lifetime and then 70 years. When Jonny Trunk got into a conversation with Noel Gallagher about copyright laws recently, the writer of Wonderwall said he "didn't give a shit" about his recordings becoming public domain. "He knows it's about publishing," says Trunk. "The money isn't in making new Beatles albums. That's over."

Unlike Paul McCartney, Cliff Richard only ever wrote the odd song, and none of his A-sides; he would never make a living from publishing, so it's easier to understand his grievances with copyright term. However, the EU ruling doesn't attempt to solve the biggest problem for older performers: they are dependent on the terms of their recording contracts, drawn up years ago by record companies. Cliff, in a position of strength, will have renegotiated his deal with EMI many times over the years. Craig Douglas, in a position of weakness, almost certainly won't.

The pioneering work in high-end reissues of public domain recordings will now be stemmed, along with the petrol-station cheapies. The recordings they have salvaged will no longer belong to the public. Craig Douglas and the other minor stars of the 60s won't get the chance to reissue their own recordings and make money for themselves. That sounds like copyright theft to me.

Public domain: Three great albums that depended on the lack of copyright

Round the Town: Following Grandfather's Footsteps – A Night at the London Music Hall (Bear Family, 2000)

A definitive four disc box with a hardback book that states a case for music hall as Britain's equivalent of the blues. Some of it is mawkish, some very funny (Sam Mayo's Things Are Worse in Russia), some quite filthy (May Moore Duprez's Won't You Come Dear Into the Park?) but it is compiled from such a wide array of labels, many long defunct, that to license every track individually would have been almost impossible. With public domain recordings, the story can be told.

The First British Hit Parade (Acrobat, 2003)

More a social history document than a CD. Al Martino's Here In My Heart is widely known as the first No 1, but who was at No 2 that week in 1952? It was Jo Stafford's sensual and exotic You Belong To Me. In fact, Al's Neapolitan ballad is possibly the worst song in this whole chart, made up of just 15 songs. There's wild west drama from Frankie Laine (High Noon), a melty Rosemary Clooney ballad (Half As Much), and even a revival for Vera Lynn, cheering on our boys in Korea with the rather sweet Forget Me Not. Just four years later, pop had changed completely.

We're Gonna Rock, We're Gonna Roll (Proper, 2005)

The roots of modern pop over a four-disc set. Many historians still hail Ike Turner and Jackie Brenston's Rocket 88 as the first rock'n'roll record, but here are dozens of other postwar claimants, divided into hillbilly bop, blues and doo wop, with a chronological fourth disc of tracks that blend all three, peaking with Elvis's That's All Right Mama and Bill Haley's Rock Around the Clock in 1954. The title is taken from a prophetic and rumbustious 1947 Wild Bill Moore recording. I'll give him the gold medal.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion