A radio host recently "referred to me as a Communist," says Musopen's Aaron Dunn. Music professors berate him by e-mail because his project is "like Napster." Dunn's crime? Setting music free.

In fact, though, Dunn's version of "freedom" looks little like Napster. Instead of distributing a recording without permission, Dunn raises money, hires orchestras to record terrific classical music ("I was a bassoon student," he says) that has fallen into the public domain, and then makes those recordings available to anyone, for any reason.

Those reasons might include using Beethoven's "Für Elise" in an indie film—indie filmmakers being some of Musopen's heaviest users—but Dunn has heard from shows like Mythbusters who also needed a bit of classical music for a segment. Wikipedia uses Musopen music to illustrate its entries on classical music.

People are willing to fund the idea. "Someone offered me $1,000 yesterday and asked how much Smetana I could record," Dunn told me, but funding for the part-time project has been sporadic to date.

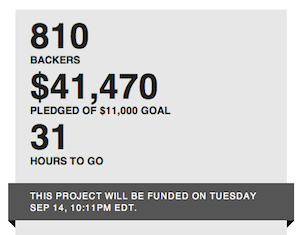

To drum up the excitement and donor base needed to give Musopen ongoing life, Dunn put the project on Kickstarter, seeking $11,000 to "hire an internationally renowned orchestra to record and release the rights to: the Beethoven, Brahms, Sibelius, and Tchaikovsky symphonies. We have price quotes from several orchestras and are ready to hire one, pending the funds." The project had a goal, a deadline, and a sense of urgency, all elements that Musopen's fundraising has lacked in the past.

With one day left to go, the Kickstarter projected has now secured more than $41,000, much of it after recently being featured on Slashdot. Intoxicated with the support and the promise of cash, Dunn has big dreams. He could hire a "brand-name" orchestra like the London Philharmonic, for instance. Sure, it would burn up all of the money and only generate a single symphony, but what a symphony it would be.

The other main alternative is to look "east"—Eastern Europe boasts tremendous orchestras that will record for a fraction of the price charged by their big-name Western counterparts. Hiring Prague's terrific philharmonic would cost only $10,000 to $15,000, for instance, but the recording wouldn't give Musopen the same cachet and publicity—both important considerations as Dunn tries to turn his baby into a truly sustainable organization.

And, as Dunn is learning, when you raise money socially, your donors have... strong ideas, and they can be quite vocal in expressing them. The donors will soon get to vote on how the money should be allocated, with Dunn planning a blind orchestral listening test to help people decide.

This is significant step up for Musopen. When we first profiled the site back in 2008, most of its recordings came from groups like the Davis High School Symphony Orchestra and Oldham Music Centre Youth Wind Band—fine institutions, but not quite the same as a big professional orchestra. Now Dunn is entertaining the idea of using the London Philharmonic, even as he ponders his many other projects: an open-source music theory textbook is in the work, for instance.

He has heard from musicians skeptical about Musopen. If it takes off, they fear that Musopen will harm the market for orchestral recordings and licensing, a key source of revenue for cash-strapped orchestras. But Dunn isn't out to make life more difficult for musicians, and he argues that "Glen Gould will always be the default" when it comes to Bach's Goldberg Variations, for instances. As for their bread-and-butter, live performances, Dunn hopes that more accessible music will lead to more interest in live concerts.

Besides, any pain that such a model causes must be set next to the huge upside for consumers, indie filmmakers, libraries, and universities: free access to high-quality recordings of some of the West's best music.

Dunn's highest hope now is that he might improbably raise more than $50,000—five times the hoped-for amount—by the time his Kickstarter project closes.

reader comments

85