Unless government officials make a major U-turn in the next few days, many British scientists will soon be blocked from speaking out on key issues affecting the UK – from climate change to embryo research and from animal experiments to flood defences. This startling, and highly controversial, state of affairs follows a Cabinet Office decision, revealed by the Observer in February, that researchers who receive government grants will be banned, as of 1 May, from using the results of their work to lobby for changes in laws or regulations.

The aim of the Cabinet Office edict was to stop NGOs from lobbying politicians and Whitehall departments using the government’s own funds. The effect, say senior scientists, campaigners and research groups, will be to muzzle scientists from speaking out on important issues. The government move is a straightforward assault on academic freedom, they argue.

These critics highlight examples such as those of sociologists whose government-funded research shows new housing regulations are proving particularly damaging to the homeless; ecologists who discover new planning laws are harming wildlife; or climate scientists whose findings undermine government energy policy. All would be prevented from speaking out under the new grant scheme as it stands.

For its part, the Cabinet Office promised to consider the introduction of exemptions to the system – two months ago. Scientists receiving government grants could receive waivers that would allow them to publicly debate key issues raised by their work, it was suggested. Since then, nothing has happened. Officials now have two weeks before the original clause is implemented.

“This is extremely worrying,” says Cambridge zoologist Professor William Sutherland. “The government already has a bad track record for not following good scientific advice. Its moves over badger-culling and over the way it has tackled flooding in the Somerset levels are examples of the poor decisions it has made. If they go ahead with this new anti-lobbying clause – and they are leaving it very late if they are not going ahead – then we will have many more poor decisions being made by government for the simple reason that it will have starved itself of proper scientific advice.”

This point was backed by Fiona Fox, head of the Science Media Centre. “Politicians don’t have to agree with scientists, but does anyone believe we will make better decisions without hearing what the evidence says on flooding, climate change, statins and e-cigarettes?” she asked.

“The anti-lobbying clause will send some of our best researchers back to the relative safety of the laboratory and away from the media fray they already fear. That will be a victory for ignorance and a blow for the evidence-based policy that our politicians claim to want.”

Since its anti-lobbying plan was announced, the Cabinet Office has been deluged with protests, which include a petition launched by Bob Ward, policy and communications director at the Centre for Climate Change Economics and Policy. Signed by more than 12,000 people, it urges that the anti-lobbying clause be dropped immediately.

This demand was followed up last week by Ward in a letter to Matt Hancock, minister for the Cabinet Office, in which he argued that the government should not now use the political “purdah” of the forthcoming local elections as a reason for refusing to make any further statements on the issue. “I urge you to announce, without delay, that universities and research institutes will be exempt from the new anti-lobbying clause,” Ward writes. Hancock has yet to reply.

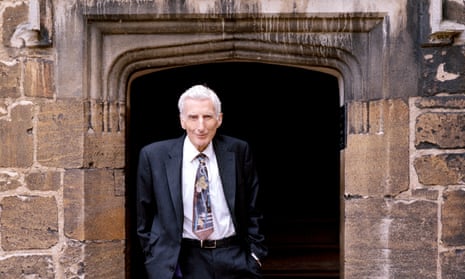

Not every scientist or campaigner believes it is too late, however. “I still think the government will come up with a solution,” said Sir Martin Rees, the astronomer royal. “It would be far too damaging to allow this clause to proceed and I think there will be an exemption made for scientists getting government grants.”

Sarah Main, director of the Campaign for Science and Engineering, has also been in close negotiations with the Cabinet Office over the issue and is also hopeful. “Scientists have been understandably vexed about this, but I have great hope that the government will soon provide us with a solution that will allow researchers to continue to lobby and give advice.”

Certainly, negotiations appear to be continuing. Last week a spokesman for the Department for Business Innovation and Skills – which is in charge of science grant administration – told the Observer that it was still discussing with the research community “what clarification may be necessary to ensure that research is not adversely affected in any way” by the anti-lobbying clause.

Such a clarification will not get the Cabinet Office off the hook, however – for, as both Rees and Main point out, even if lobbying waivers are agreed in the next two weeks, a great deal of harm has already been done over the past two months. In particular, relations between scientists and government have been soured and a great deal of unnecessary time has been wasted.

“This whole process has been very worrying – unnecessarily so as well,” says Rees. “And I think there will be a legacy. Young scientists who are just getting their first grants will be seriously concerned that their views and opinions are not going to be welcomed by government. This is not going to encourage them to speak out in future.”

We therefore face one of two outcomes over the next two weeks. The best we can expect is an announcement in a few days that scientists are to be exempted in some way from the proposed anti-lobbying clause. According to this scenario, the government merely bungled its policymaking and introduced a rule without contemplating its consequences. Then, in dragging its heels in putting right its mistake, it caused considerable damage to its relations with its scientists. That is the best-case scenario.

The alternative outcome would be one in which the government proceeds with its anti-lobbying stance and makes our scientists comply with its new clause in order to stop them from embarrassing government projects in future. That would indeed be an assault on academic freedom.

So let’s hope this is not really a conspiracy – just another government cock-up.