The Man Who Wouldn’t Die

The plot to kill Michael Malloy for life-insurance money seemed foolproof—until the conspirators actually tried it

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20120207104107new-yorks-fantastic-murder.jpg)

The plot was conceived over a round of drinks. One afternoon in July 1932, Francis Pasqua, Daniel Kriesberg and Tony Marino sat in Marino’s eponymous speakeasy and raised their glasses, sealing their complicity, figuring the job was already half-finished. How difficult could it be to push Michael Malloy to drink himself to death? Every morning the old man showed up at Marino’s place in the Bronx and requested “Another mornin’s morning, if ya don’t mind” in his muddled brogue; hours later he would pass out on the floor. For a while Marino had let Malloy drink on credit, but he no longer paid his tabs. “Business,” the saloonkeeper confided to Pasqua and Kriesberg, “is bad.”

Pasqua, 24, an undertaker by trade, eyed Malloy’s sloping figure, the glass of whiskey hoisted to his slack mouth. No one knew much about him—not even, it seemed, Malloy himself—other than that he had come from Ireland. He had no friends or family, no definitive date of birth (most guessed him to be about 60), no apparent trade or vocation beyond the occasional odd job sweeping alleys or collecting garbage, happy to be paid in alcohol instead of money. He was, wrote the Daily Mirror, just part of the “flotsam and jetsam in the swift current of underworld speakeasy life, those no-longer-responsible derelicts who stumble through the last days of their lives in a continual haze of ‘Bowery Smoke.’ ”

“Why don’t you take out insurance on Malloy?” Pasqua asked Marino that day, according to another contemporary newspaper report. “I can take care of the rest.”

Marino paused. Pasqua knew he’d pulled off such a scheme once before. The prior year, Marino, 27, had befriended a homeless woman named Mabelle Carson and convinced her to take out a $2,000 life insurance policy, naming him as the beneficiary. One frigid night he force-fed her alcohol, stripped off her clothing, doused the sheets and mattress with ice water, and pushed the bed beneath an open window. The medical examiner listed the cause of death as bronchial pneumonia, and Marino collected the money without incident.

Marino nodded and motioned to Malloy. “He looks all in. He ain’t got much longer to go anyhow. The stuff is gettin’ him.” He and Pasqua glanced over at Daniel Kriesberg. The 29-year-old grocer and father of three would later say he participated for the sake of his family. He nodded, and the gang set into motion a macabre chain of events that would earn Michael Malloy cult immortality by proving him nearly immortal.

Pasqua offered to do the legwork, paying an unnamed acquaintance to accompany him to meetings with insurance agents. This acquaintance called himself Nicholas Mellory and gave his occupation as florist, a detail that one of Pasqua’s colleagues in the funeral business was willing to verify. It took Pasqua five months (and a connection with an unscrupulous agent) to secure three policies—all offering double indemnity—on Nicholas Mellory’s life: two with Prudential Life Insurance Company and one with Metropolitan Life Insurance Company. Pasqua recruited Joseph Murphy, a bartender at Marino’s, to identify the deceased as Michael Malloy and claim to be his next of kin and beneficiary. If all went as planned, Pasqua and his cohorts would split $3,576 (about $54,000 in today’s dollars) after Michael Malloy died as uneventfully and anonymously as he had lived.

The “Murder Trust,” as the press would call them, now included a few other Marino’s regulars, including petty criminals John McNally and Edward “Tin Ear” Smith (so-called even though his artificial ear was made of wax), “Tough Tony” Bastone and his slavish sidekick, Joseph Maglione. One night in December 1932 they all gathered at the speakeasy to commence the killing of Michael Malloy.

The Murder Trust (clockwise from top left): Daniel Kreisberg, Joseph Murphy, Frank Pasqua, and Tony Marino. From On the House.

To Malloy’s undisguised delight, Tony Marino granted him an open-ended tab, saying competition from other saloons had forced him to ease the rules. No sooner did Malloy down a shot than Marino refilled his glass. “Malloy had been a hard drinker all his life,” one witness said, “and he drank on and on.” He drank until Marino’s arm tired from holding the bottle. Remarkably, his breathing remained steady; his skin retained its normally ruddy tinge. Finally, he dragged a grungy sleeve across his mouth, thanked his host for the hospitality, and said he’d be back soon. Within 24 hours, he was.

Malloy followed this pattern for three days, pausing only long enough to eat a complimentary sardine sandwich. Marino and his accomplices were at a loss. Maybe, they hoped, Malloy would choke on his own vomit or fall and slam his head. But on the fourth day Malloy stumbled into the bar. “Boy!” he exclaimed, nodding at Marino. “Ain’t I got a thirst?”

Tough Tony grew impatient, suggesting someone simply shoot Malloy in the head, but Murphy recommended a more subtle solution: exchanging Malloy’s whiskey and gin with shots of wood alcohol. Drinks containing just four percent wood alcohol could cause blindness, and by 1929 more than 50,000 people nationwide had died from the effects of impure alcohol. They would serve Malloy not shots tainted with wood alcohol, but wood alcohol straight up.

Marino thought it a brilliant plan, declaring he would “give all of the drink he wants…and let him drink himself to death.” Kriesberg allowed a rare display of enthusiasm. “Yeah,” he added, “feed ’im wood alcohol cocktails and see what happens.” Murphy bought a few ten-cent cans of wood alcohol at a nearby paint shop and carried them back in a brown paper bag. He served Malloy shots of cheap whiskey to get him “feeling good,” and then made the switch.

The gang watched, rapt, as Malloy downed several shots and kept asking for more, displaying no physical symptoms other than those typical of inebriation. “He didn’t know that what he was drinking was wood alcohol,” reported the New York Evening Post, “and what he didn’t know apparently didn’t hurt him. He drank all the wood alcohol he was given and came back for more.”

Night after night the scene repeated itself, with Malloy drinking shots of wood alcohol as fast as Murphy poured them, until the night he crumpled without warning to the floor. The gang fell silent, staring at the jumbled heap by their feet. Pasqua knelt by Malloy’s body, feeling the neck for a pulse, lowering his ear to the mouth. The man’s breath was slow and labored. They decided to wait, watching the sluggish rise and fall of his chest. Any minute now. Finally, there was a long, jagged breath—the death rattle?—but then Malloy began to snore. He awakened some hours later, rubbed his eyes, and said, “Gimme some of th’ old regular, me lad!”

The storefront for Tony Marino's speakeasy, 1933. From On the House. (Ossie LeViness, New York Daily News photographer.)

The plot to kill Michael Malloy was becoming cost-prohibitive; the open bar tab, the cans of wood alcohol and the monthly insurance premiums all added up. Marino fretted that his speakeasy would go bankrupt. Tough Tony once again advocated brute force, but Pasqua had another idea. Malloy had a well-known taste for seafood. Why not drop some oysters in denatured alcohol, let them soak for a few days, and serve them while Malloy imbibed? “Alcohol taken during a meal of oysters,” Pasqua was quoted as saying, “will almost invariably cause acute indigestion, for the oysters tend to remain preserved.” As planned, Malloy ate them one by one, savoring each bite, and washed them down with wood alcohol. Marino, Pasqua and the rest played pinochle and waited, but Malloy merely licked his fingers and belched.

At this point killing Michael Malloy was just as much about pride as about a payoff—a payoff, they all griped, that would be split among too many conspirators. Murphy tried next. He let a tin of sardines rot for several days, mixed in some shrapnel, slathered the concoction between pieces of bread and served Malloy the sandwich. Any minute, they thought, the metal would start slashing through his organs. Instead, Malloy finished his tin sandwich and asked for another.

The gang called an emergency conference. They didn’t know what to make of this Rasputin of the Bronx. Marino recalled his success with Mabelle Carlson and suggested that they ice Malloy down and leave him outside overnight. That evening Marino and Pasqua tossed Malloy into the back seat of Pasqua’s roadster, drove in silence to Crotona Park and lugged the unconscious man through heaps of snow. After depositing him on a park bench, they stripped off his shirt and dumped bottles of water on his chest and head. Malloy never stirred. When Marino arrived at his speakeasy the following day, he found Malloy’s half-frozen form in the basement. Somehow Malloy had trekked the half-mile back and persuaded Murphy to let him in. When he came to, he complained of a “wee chill.”

February neared. Another insurance payment was due. One of the gang, John McNally, wanted to run Malloy over with a car. Tin Ear Smith was skeptical, but Marino, Pasqua, Murphy and Kriesberg were intrigued. John Maglione offered the services of a cabdriver friend named Harry Green, whose cut from the insurance money would total $150.

They all piled into Green’s cab, a drunken Malloy strewn across their feet. Green drove a few blocks and stopped. Bastone and Murphy dragged Malloy down the road, holding him up, crucifixion-style, by his outstretched arms. Green gunned the engine. Everyone braced. From the corner of his eye, Maglione saw a quick flash of light.

“Stop!” he yelled.

The cab lurched to a halt. Green determined it had just been a woman turning on the light in her room, and he prepared for another go. Malloy managed to leap out of the way—not once, but twice. On the third attempt Green raced toward Malloy at 50 miles per hour. Maglione watched through splayed fingers. With every second Malloy loomed larger through the windshield. Two thuds, one loud and one soft, the body against the hood and then dropping to the ground. For good measure, Green backed up over him. The gang was confident Malloy was dead, but a passing car scared them from the scene before they could confirm.

It fell to Joseph Murphy, who had been cast as Nicholas Mellory’s brother, to call morgues and hospitals in an attempt to locate his missing “sibling.” No one had any information, nor were there any reports of a fatal accident in the newspapers. Five days later, as Pasqua plotted to kill another anonymous drunk—any anonymous drunk—and pass him off as Nicholas Mellory, the door to Marino’s speakeasy swung open and in limped a battered, bandaged Michael Malloy, looking only slightly worse than usual.

His greeting: “I sure am dying for a drink!”

What a story he had to tell—what he could remember of it, anyway. He recalled the taste of whiskey, the cold slap of night air, the glare of rushing lights. Then, blackness. Next thing he knew he woke up in a warm bed at Fordham Hospital and wanted only to get back to the bar.

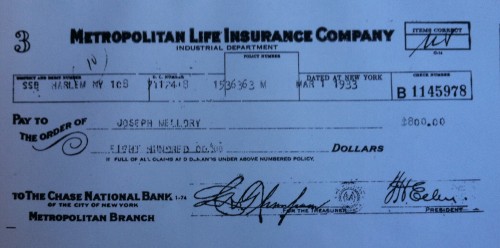

A check for $800 from the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company, the only money the Murder Trust collected. From On The House.

On February 21, 1933, seven months after the Murder Trust first convened, Michael Malloy finally died in a tenement near 168th Street, less than a mile from Marino’s speakeasy. A rubber tube ran from a gas light fixture to his mouth and a towel was wrapped tightly around his face. Dr. Frank Manzella, a friend of Pasqua’s, filed a phony death certificate citing lobar pneumonia as the cause. The gang received only $800 from Metropolitan Life Insurance Company. Murphy and Marino each spent their share on a new suit.

Pasqua arrived at the Prudential office confident he would collect the money from the other two policies, but the agent surprised him with a question: “When can I see the body?”

Pasqua replied that he was already buried.

An investigation ensued; everyone began talking, and everyone eventually faced charges. Frank Pasqua, Tony Marino, Daniel Kriesberg and Joseph Murphy were tried and convicted of first-degree murder. “Perhaps,” one reporter mused, “the grinning ghost of Mike Malloy was present in the Bronx County Courthouse.” The charter members of the Murder Trust were sent to the electric chair at Sing Sing, which killed them all on the very first try.

Sources:

Books: Simon Read, On the House: The Bizarre Killing of Michael Malloy. New York: Berkley Books, 2005; Deborah Blum, The Poisoner’s Handbook: Murder and the Birth of Forensic Medicine. New York: Penguin Press, 2010. Alan Hynd, Murer, Mayhem and Mystery: An Album of American Crime. New York: Barnes, 1958.

Articles: “Malloy the Mighty,” by Edmund Pearson. The New Yorker, September 23, 1933; “When Justice Triumphed.” Atlanta Constitution, November 19, 1933; “Weird Killing Plot Unfolded.” Los Angeles Times, May 14, 1933; “Killed for Insurance.” The Washington Post, May 13, 1933; “Police Think Ring Slew Capital Girl.” The Washington Post, May 14, 1933; “Four to Die for Killing by Gas After Auto, Rum, Poison Fail.” The Washington Post, October 20, 1933; “Last Malloy Killer Will Die Tomorrow.” New York Times, July 4, 1934. “3 Die At Sing Sing for Bronx Murder.” New York Times, June 8, 1934; “Murder Trial Is Told of Insurance Dummy.” New York Times, October 6, 1933; “The Durable Malloy.” The Hartford Courant, September 22, 1934; “Last Malloy Killer Will Die Tomorrow.” New York Times, July 4, 1934.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/karen-abbot-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/karen-abbot-240.jpg)