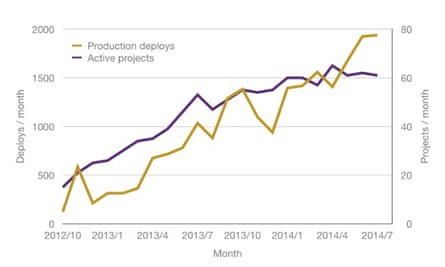

In 2011 the Guardian deployed the software behind the website 25 times. It was a laborious and fairly manual process. In 2014 we made more than 24,000 highly automated production deployments. Why and how did we do it?

Why deploy so frequently?

Continuous Delivery is the ability to ship working software to production at any point. We believe that the only way to categorically prove software is production ready is to deploy it to production. Automated testing and pre-production environments can increase your confidence, but they can never account for everything that can possibly go wrong.

Before we moved to Continuous Delivery, releasing to production was a slow, cumbersome process that involved a round of regression testing, collating a list of all the changes and a 12 step semi-automated process performed by a team who weren’t involved in making those changes. If we needed to make an urgent change or fix, it needed to be applied to multiple branches and there was nervousness around whether the deployment process itself might cause issues.

We relied on pre-production environments to try to gather feedback, but nobody takes staging environments seriously. It is unreasonable to expect people with busy day jobs to use pre-production tools in a way that even closely resembles real use. Small groups of user testers for a website are never a substitute for a global audience.

One of the most frequently quoted reasons for adopting Continuous Delivery is to deliver the value of software sooner by releasing earlier. Whilst this is a benefit, given that we had been releasing once a fortnight the incremental value of doing so wouldn’t have justified the effort involved.

What has been transformative for us is the massive reduction in the amount of time to get feedback from real users. Practices like Test Driven Development and Continuous Integration can go some way to providing shorter feedback loops on whether code is behaving as expected, but what is much more valuable is a short feedback loop showing whether a feature is actually providing the expected value to the users of the software.

The other major benefit is reduced risk. Having a single feature released at a time makes identifying the source of a problem much quicker and the decision over whether or not to rollback much simpler. Deploying much more frequently hardens the deployment process itself. When you’re deploying to production multiple times a day, there’s a lot more opportunity and incentive for making it a fast, reliable and smooth process. Having a hardened deploy process also means that pushing out a fix for a bug at 5pm on a Friday afternoon becomes a low risk, routine activity.

Not everyone was convinced from the outset, though. It can be counter-intuitive to suggest that releasing more often reduces risk.

How did we make it a reality?

In order to convince everyone of the value of Continuous Delivery, we rolled out the new release process slowly. We started with lower profile, less risky systems using Google App Engine which made deploying frequently much easier. Once we had this in place, we made sure to make the most of it. We deployed frequently and sought opportunities to provide small features or fixes rapidly. This meant that users became advocates for Continuous Delivery, asking why other software couldn’t be delivered in the same way.

Introducing Continuous Delivery involves a carefully choreographed combination of both cultural and technical change. We knew that in order to make Continuous Delivery work for us we needed to improve the integration between our development and operations teams, and make sure they both understood and were working towards the goals of the organisation as a whole. Practically, there seemed little point moving to Continuous Delivery without breaking away from the culture of a fortnightly release cycle. In hindsight this was at odds with the success we’d had introducing Google App Engine, but we found ourselves waiting for a cultural change before implementing tooling to support Continuous Delivery. As a result the adoption of Continuous Delivery stagnated.

We eventually decided to start work on the tooling anyway. Whilst we haven’t reached DevOps nirvana, once developers were deploying to production more frequently they became a lot more interested in how their code actually behaved in that environment. Tooling changes and cultural changes moved forwards in parallel and reinforced each other.

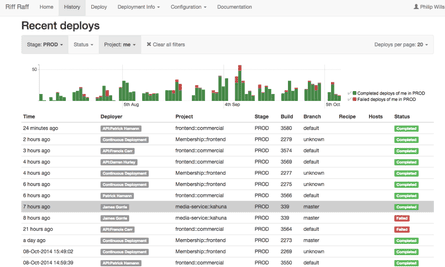

RiffRaff, a tool for simple deployment

We were already using TeamCity as an off-the-shelf Continuous Integration server, but we were clear that building and testing a deployable artifact wasn’t something we wanted to mix with the act of actually deploying it. In order to deploy everything we wanted to, we knew some processes would be different but we wanted to limit the number of possible deploy methods so that similar systems were deployed in the same way. We couldn’t find a tool which fit our needs, so we started writing one ourselves known as RiffRaff.

Again, we took an incremental approach. At first it was a command line tool which could only deploy Java webapps within our data centres. It’s now a push button webapp that can deploy a variety of different types of application to internal and cloud hosts as well as uploading files to S3, applying CloudFormation templates and pushing CDN configuration updates. It was started by members of our development team and is written in Scala, which isn’t well known as a systems language. We were lucky enough to have a member of the operations team with a background in development who was keen to learn and took over leading its direction.

This operational focus helped us to identify and eliminate a deployment antipattern. Prior to RiffRaff the operations team would carry out all deployments. A developer would raise a ticket for operations to deploy a particular version of an application into production. Operations would pick up the ticket within an hour or so, carry out the deployment according to instructions maintained on a wiki and then contact the developer so that they could test the deployment had worked. Whilst it was important that operations knew that a deploy had happened in case a deploy broke something, they didn’t really add anything to the process. Operations simply held the keys and acted as gatekeeper. When RiffRaff was developed to give developers direct access to production deployments, concerns like traceability were front and centre. When things have gone wrong, identifying who changed what and when has been trivial.

One of the strengths of RiffRaff has been the flexibility provided by the integration endpoints. A comprehensive API including web-hooks allows developers to integrate RiffRaff information into dashboards, and easily start and monitor deploys from their own tool chains. So whilst we are providing a deployment platform for people to use, teams are able to use it as they see fit.

Monitoring and alerting

Smaller releases make it simpler to identify the cause of incidents, and having the codebase always ready to deploy makes applying fixes to problems easier. What isn’t addressed directly by Continuous Delivery is the time to detect that there is an incident in the first place. To aid that we’ve put a different focus on monitoring and alerting. Whilst gathering vast numbers of metrics can be useful during diagnosis, monitoring what people are actively looking at or alerting from fewer metrics are better. High level, business-focused metrics have produced fewer false positives, whilst capturing a wider range of issues than other approaches we’ve tried.

We view an application with a long uptime as a risk. It can be a sign that there’s fear to deploy it, or that a backlog of changes is building up, leading to a more risky release. Even for systems that are not being actively developed, there’s value in deploying with some regularity to make sure we still have confidence in the process. One note of caution: deploying so frequently can mask resource leaks. We once had a service fail over a bank holiday weekend, as it had never previously run for three days without being restarted by a deploy!

Why not Continuous Deployment?

Continuous Delivery often gets confused with Continuous Deployment, which is the practice of releasing to production automatically on each commit. Given how often we deploy it would be reasonable to ask why we don’t go the whole hog and move to Continuous Deployment. While RiffRaff is used by many projects for Continuous Deployment in pre-production environments, only a few use it to push automatically into production. The automated checks to validate a deploy are not mature enough to rely on, and we found that when people didn’t manually initiate a deploy they were less likely to monitor metrics during and after it.

As an example, we experimented with Continuously Deploying some components of our new website, including a component responsible for rendering all of the football pages. To push out a new feature to production, a developer could simply merge their feature branch to master and rely on the Continuous Deployment pipeline. Some time after this was put in place part of the pipeline broke - whilst it appeared to be working, new releases were not actually being pushed into production. Developers continued to work on the assumption their changes were available to end users and it took two weeks before anyone noticed.

Roles and responsibilities

With Continuous Delivery tooling in place, the culture of project teams and the roles of team members began to shift. We’ve noticed changes in three roles:

- Developers are doing operations and support as products shift to full stack ownership

- QA have shifted from manual regression testing to automated tests and exploratory testing

- Operations have shifted from running products and being production gatekeepers to being consultants and watchmen (auditing product implementations)

- Release management is no longer a dedicated role, with each product team able to release when they like and RiffRaff providing centralised reporting

Adopting Continuous Delivery has not been simple, quick, or cheap. We’ve spent at least a year’s worth of a developer’s time on deployment tools alone. We believe this cost has been more than justified by massively reducing regression testing cycles and eliminating the dedicated release manager role, even before taking account of the less tangible benefits of a faster feedback cycle. Continuous Delivery has made us more resilient, allowed us to build more valuable software, and also made delivering software more fun. Hearing a suggestion from a user, delivering some approximation of it an hour later, and then iterating with them to make the most of it is a hugely rewarding way of producing software.

- This was first published as part of the Build Quality In anthology of Continuous Delivery and DevOps experience reports.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion