Just before one o’clock on a Tuesday lunchtime last summer, about 30 men and three women were mingling at the bar of the Garrick Club in London’s theatre district. The broadcaster Jeremy Paxman was leaning back on a low sofa, chatting with a young man (in this context, young means under 50). Michael Gove, the Conservative chief whip, was surrounded by a small cluster of men. After a while, Paxman stood up to say hello to Gove; they talked for a moment, laughing. Shortly after, everyone – among them a former warden of Wadham College, Oxford, and a senior adviser to the government on privatisation – made their way out of the bar for lunch.

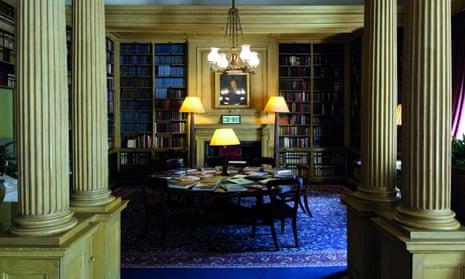

A long table – laden with silverware and glass, atop gleaming, polished wood – stretches down the middle of the club’s dining room. In front of each seat there is a starched linen napkin with “The Garrick” embroidered in red thread, and a stitched buttonhole, to help you to attach the napkin to the front of your shirt. Members who arrive by themselves gravitate to this central table. On that Tuesday, the head of the table, reserved for the oldest member of the club, was occupied by a venerable-looking individual with long grey hair and a white beard. Along the table were 10 other men (white), all in suits (dark), the most youthful perhaps in his mid-60s, their grey heads bent together in conversation.

Members love the Garrick passionately; when the Shakespearean actor Sir Donald Sinden died last year he was buried in a coffin painted with the club tie’s distinctive salmon and cucumber stripes. They cherish the club’s heritage: curious bits of theatrical memorabilia on display in glass cabinets by the entrance to the bar include a flower worn by the French actress Sarah Bernhardt and Noel Coward’s scent bottle. The club’s art collection was recently enhanced by the purchase, for £6m, of two 18th-century portraits by Johann Zoffany of the actor David Garrick, in whose honour the club was founded.

The Garrick is one of a handful of London’s gentlemen’s clubs that do not admit women as members. (“A club,” wrote Anthony Lejeune in his 1979 book, The Gentlemen’s Clubs of London, “is a place where a man goes to be among his own kind.”) Women can go as guests, but are not allowed to join in their own right, and club convention still dictates that they don’t sit at the central dining table. Members describe the club as a place of sanctuary, away from the 21st-century grime of Soho’s casinos and bars. Most enjoy the club’s maleness, explaining that it is a peaceful environment where men can relax, uninhibited by pressure to turn on the “peacock behaviour” that comes when there are women to be impressed.

But that could all change this summer. Beneath the grand staircase in the entrance hall, a collection of leather armchairs is arranged around a fireplace, where sleepy-looking men go for a rest. This under-the-stairs area is screened off from the club’s lobby behind a purple velvet curtain and is one of the areas that female guests are never allowed to enter. Pinned to a board in this private area are details of a motion by the lawyer and former Labour MP Bob Marshall-Andrews, proposing that women should be allowed to join the club.

The lists of names for and against the motion are peppered with distinguished acronyms: QC, Rt Hon, OBE, KCMG, CBE, MP. Those favouring admitting women are more instantly recognisable – the actors Stephen Fry and Hugh Bonneville, Michael Gove, journalists and broadcasters. The “against” list appears underneath a declaration punctuated by emphatic capitals and underlining: “The following members wish it to be known that they are OPPOSED to Bob Marshall-Andrews’s resolution in favour of admitting women members and instead wish to maintain the status quo.” The names include a couple of former Conservative MPs and 11 QCs; there is the owner of a rare-editions bookshop, an agent for classical musicians, a wine expert, a former chess grandmaster and a few doctors with private Harley Street practices. Their professions suggest gentlemen of a certain age. Both lists represent only a fraction of the club’s overall membership of about 1,400 – but this early show of hands suggests women may not get the chance to join any time soon: with 172 opposing the motion and 156 in favour. A two-thirds majority is required for change to be approved.

The protracted history of the fight to get women admitted to the Garrick stretches over two decades and, if past experience is anything to go by, it is likely that this summer’s battle will be bitter and divisive. At the last attempt, in 2011, when a woman’s name was inscribed in the nominations book, an irate member ripped the page from the leather-bound ledger and screwed it into a ball. “A small gang of diehards wrote some nasty things beneath the nomination – which was really rather ungentlemanly,” one member recalled.

The Garrick was founded in 1831 in Covent Garden as a place where “actors and men of refinement could meet on equal terms” – this was a time when actors were not generally considered to be respectable members of society. In the preceding decades, St James’s and Pall Mall had already been colonised by vast gentlemen’s clubs, each offering a haven for different tribes. White’s was for Tories, Brooks’s for their political rivals, the Whigs, and Boodle’s for the country set. The Athenaeum catered for “men of science, literature and art”, while the Travellers Club was a place where gentlemen who were able to show they had travelled 500 miles from London could discuss their experiences; the Carlton welcomed political conservatives; the Reform Club, for liberal supporters of the 1832 Reform Act, opened a little later in 1836.

Take a walk up St James’s, cutting through the area of London still known as clubland, and you can see the beautiful Palladian buildings that house Brooks’s and White’s. St James’s remains a curiously male part of London; specialist shops in nearby Jermyn Street sell expensive grooming paraphernalia for men – badger shaving brushes and sandalwood soaps. Nearby, one can also find John Lobb Bootmaker (est 1866) and Geo F Trumper, the gentleman’s barber (est 1875). Inside the gentlemen’s clubs, there are dark, wood-panelled entrances with green baize noticeboards, and rooms decorated with chandeliers and large mirrors. The bow window at the front of Boodle’s was once occupied by Winston Churchill, who liked to sit and smoke his cigar, attracting admiring crowds.

Members of the nearby clubs value their unchanging atmosphere. “A good club should be a refuge from the vulgarity of the outside world, a reassuringly fixed point, the echo of a more civilized way of living, a place where (as was once said of an Oxford college) people still prefer a silver salt cellar which doesn’t pour to a plastic one which does,” Lejeune wrote.

Until the mid-20th century, there was little question of women being admitted to these clubs, since, on the whole, there were almost no women in the professional and artistic fields from which members were drawn. Slowly, over recent decades, a few have begun to allow women in – the Reform Club in 1981, the Athenaeum in 2002, the Carlton Club in 2008. Many of these decisions were commercial – with rapidly ageing membership, new (female) blood helps bring in vital funds.

A few remain unrepentant about their men-only status. With the exception of the Queen, women are never allowed past the front door of White’s, London’s most aristocratic club. David Cameron’s father was chairman here, but Cameron decided to resign when he became leader of the Conservative party. (His stated view 18 months ago on all-male clubs was that they “look more to the past than they do to the future”.)

When I called Pratt’s Club to ask whether women were admitted, the friendly steward (a woman) explained that they were not, with a logic that wasn’t entirely easy to follow: “They still don’t allow women in because it is a supper club; we only open at seven at night. Only at private lunches – women are allowed then – as we do the lunches on a different floor.” She did not explain why seven is too late for women to venture out, or if there is a reason why women must have lunch on a different floor. At the Turf Club, the person who answered the phone would not confirm whether or not women are admitted (they aren’t), and promptly hung up.

Still, the question of reform does surface from time to time. In 2012, at the annual general meeting of the Travellers Club, members debated a modest proposal to allow “lady heads of some diplomatic missions in London to be accorded honorary membership for the duration of their tenure”. International diplomats and ambassadors use the club’s facilities, occasioning some members’ embarrassment that female ambassadors from around the world are not able to join along with their junior male colleagues. The motion was, however, firmly rejected.

Yet the issue refused to go away. The following year, Anthony Layden, then chairman of the Travellers Club, and a former ambassador to Libya and Morocco, proposed a consultation on the wider question of whether women should be admitted as members. In April 2014, after canvassing responses from almost 200 members, he delivered his 8,000-word report. Many of the candid responses he received reveal a dislike of women and unease in their company. One member said he would “find it distinctly inconvenient to have to sit up and look civilised because a lady might appear”. Another commented that his “experience of the club table at the Oxford and Cambridge Club, where one does unfortunately encounter lady members, is that their presence leads to very different and far less enjoyable themes of conversation”. Others worried that women would jeopardise the club’s status as a place where one can enjoy “male banter, without having to bother with the etiquette that one inevitably must adhere to in female company (whether it be offering her drinks, waiting for her to eat, or standing when she arrives or leaves)”.

Those in favour of change said: “It would be unimaginable to refuse membership on the basis of race or religion, and I cannot reconcile why doing so on the basis of gender is any more acceptable.” “If we do not change, normal men will cease to join: we shall gradually become a despised refuge for misogynists and eccentrics.” They were overruled.

A significant reason why women still can’t go to the Garrick is the worldwide affection for Winnie the Pooh. In 1956, AA Milne left a quarter of the royalties from his children’s books to his club. In 2000, Disney bought out the club’s share of the rights for £40m. While other clubs welcomed women members and their membership fees, the Garrick hasn’t needed them.

The efforts of a minority group to persuade fellow members to admit women to the Garrick have so far been futile and painful. The issue was first raised seriously in 1991, when the Royalty theatre (now the Peacock) was booked for a members’ debate on the subject. The broadcaster Melvyn Bragg and the writer John Mortimer tried, and failed, to influence fellow members. At the debate, one member recalls: “A barrister speaking against the motion [to admit women] said: ‘Every now and then I ask my wife for leave to have a night out at the Garrick with the chaps. If I were to ask for leave to go to the Garrick with the chaps and chappesses it would not be granted.’ There were huge guffaws of laughter. They thought it was hilarious. The result was 70% in favour of the status quo.”

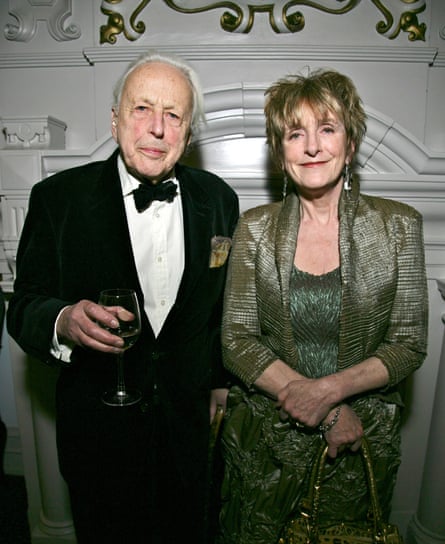

The subject wasn’t raised again for 20 years. “They were biding their time – things move slowly in this arena,” the member, who asked not to be identified, said. But in 2011, two women were nominated as prospective members: the actress Joanna Lumley, by Hugh Bonneville; and the arts broadcaster Lucinda Lambton, by her husband and former editor of the Sunday Telegraph, Sir Peregrine Worsthorne, and the economist and diplomat Peter Jay.

There was, in response, much studying of the club’s rules by senior lawyers on both sides (senior lawyers are not hard to find within the Garrick). These rules contained nothing that stipulated that women could not become members, so the arguments closed in on a discussion of whether there would be a breach of contract if an organisation that had described itself as a club “to further gentlemanly pursuits” began admitting women. The decision was that the spirit of the rules would be breached, and that the status quo should be maintained. Both Lumley and Bonneville declined to comment, but Worsthorne says the process was “very, very unpleasant”.

“Peter wrote Lucinda’s name in the candidates’ book – something that’s never been done before, in all the centuries that the Garrick has existed,” said Worsthorne, who is 90. “It caused an explosion of opinion. The club was very divided. It was really as if some crime had been committed. It was a terrible battle. Half the club got outraged that people should do this, put a woman in the book – the other half said, ‘Well, why shouldn’t they?’ It was very, very bitter. Needless to say in the end, the lawyers said it was unlawful.” He said all traces of Lambton’s nomination were snipped out of the candidates’ book with a pair of scissors.

Worsthorne and Lambton spoke to me by telephone from their house in the country, noisily correcting each other, passing the receiver from one to the other to add extra details.

“The members screwed the page up. Can you believe it?” Lambton recalled, still torn between outrage and a desire to laugh at the pettiness of it. “I suppose in the general world, it is not a major, major incident,” she said, laughing, before conceding that she had been dismayed. “I was very, very shocked by them doing it. It’s extraordinary ... It is perplexing. Very, very odd. Rubbish.”

Worsthorne was also bruised by the experience. “It did surprise me, the degree of anger. I had friends who had backed Lucy, just to be friendly to Lucy and me – and signed in our favour. They said they were treated with such rudeness by some other members, who would harangue them with anger and indignation as if they had let the side down. I didn’t think it would cause such a fracas. But I enjoy a fracas.

“It’s part of a historical growth,” he added. “At one point, all the interesting politicians were men, all the interesting judges, all the interesting doctors, writers were all men, so obviously the company of men could be very satisfactory without women being present. But nowadays, that has all changed; it’s just as likely that a woman could be a lord chief justice, so she would be interesting. Women are no longer uninteresting as professional comrades. It makes no sense to keep them out.”

Of his involvement in the failed attempt, Jay would only say (in an email): “The committee should elect those candidates who are most likely to contribute to the joy of life in it; and there is no reason to suppose that these are all men, still less that all men are so blessed.”

There is growing hostility among women in the legal profession towards a club that welcomes so many male QCs and judges, but excludes women. In 2011, Baroness Hale, Britain’s most senior female judge, the first and only woman among 12 supreme court judges – several of whom are Garrick Club members – told a law diversity forum: “I regard it as quite shocking that so many of my colleagues belong to the Garrick Club, but they don’t see what all the fuss is about.” Judges, she said, “should be committed to the principle of equality for all”.

Members protest strenuously that they glean no professional advantage from membership. However, a senior female QC, who did not wish to be named, told me that she was irritated by the continued male-only nature of the club. “Its continued predominance is one of the reasons why sexism in professions such as mine never quite goes away,” she said. She pointed out that male colleagues went from court to club, whereas female lawyers of her ranking had no time for clubs (even if they were invited to join) because they went directly home, to look after the children. The situation “is made much worse by the fact that the overwhelming majority of members have non-working wives who have devoted themselves to supporting their husbands and raising the children,” she said.

In October 2013, one north London magistrate, Jo Arden, decided to take action. At the AGM of the Magistrates’ Association, Arden proposed that three senior judges, who were Garrick members, have their honorary membership of the association removed. “Surely our association should be sending a message of inclusion, rather than honouring members of a club which practises social division,” Arden said at the meeting.

“If their lordships belonged to a club which excluded ethnic minorities, gay people, disabled people or others ... they would not have been allowed to sit on the bench. And yet there is a complete double standard when it comes to women.”

Her motion was narrowly defeated but, embarrassed, and concerned that the motion would be tabled again, the Magistrates’ Association’s trustees decided in April 2014 to abolish the notion of honorary members altogether. As a result of Arden’s campaign, Tony Blair’s lord chancellor, Lord Irvine of Lairg, the former president of the supreme court Lord Phillips, and the former lord chief justice Lord Woolf lost their honorary status.

“To say that to discriminate against women is somehow not as serious, is rubbish,” she said. She believes that the Garrick remains an influential institution. “The members tend to be very senior and they do have a very great deal of power.”

When the last Labour government drafted the 2010 Equality Act, there was some discussion of how the legislation could be used to make these clubs illegal, but this proved impossible. The legislation settled on banning clubs from excluding people on the basis of colour, but allowed them to continue rejecting women. Vera Baird, who as Labour’s solicitor general was involved in drafting the legislation, says: “We obviously looked with bared teeth at the prospect of getting rid of them [all-male gentlemen’s clubs].” However, very quickly they saw that this could not be done without also forcing a parallel ban of women’s swimming clubs or gay choirs.

Politically it was a disappointment. “Obviously you hope that an equality act is going to be able to root out inequality. As long as men are still the power brokers, having exclusive clubs just for them is going to boost that position again and again; if you allow men to recruit to their own private clubs they can continue to share that power amongst themselves, or not to share it.”

The appearance of new equalities legislation did make it illegal for the Garrick to make some areas of the club off limits to women. It is now illegal for the club to dictate that seats at the central table are just for men. Members were told about the impact of the legislation, but advised (according to a reformist member who asked not to be named) that “‘members may take women there, but the expectation is that they would feel very out of place and therefore we would advise not to bring them’. It worked – you rarely see a woman at that table.”

When members discuss why they want to preserve a men-only space, they express a wariness of women that suggests they haven’t been exposed to many as professional peers. One member said he would not be able to speak freely with people he did not consider “equals”. One member who opposes the extension of membership to women, talked about the “egalitarian atmosphere”. Those who enjoy this privileged company are not necessarily conscious that it is exclusive.

In the New Statesman last year, in a sharp portrait of the power of the great white male, the artist Grayson Perry wrote: “They dominate the upper echelons of our society, imposing, unconsciously or otherwise, their values and preferences on the rest of the population.” Perry noted that these white, middle-class, middle-aged, heterosexual men “will never admit to, or be fully aware of, the tribal advantages of [their] identity”.

For many of the members I spoke to, affection for their clubs was often rooted in a sense of nostalgia for their schooldays, with their communal dining and narrow membership base. “You’re talking about a lot of people who went to prep school with boys when they were seven, went to public school with boys when they were 12 or 13, went to university with men when they were 18 or 19, went to the inns of court with men in their 20s,” said one Garrick member.

“Women on the whole gossip about their intimate lives; men banter: they discuss things objectively in ways which are not emotional,” said the writer Tom Bower, who opposes allowing women members. “There are no personal confessions, things like that, which women spend a lot of time doing. There is laughter,” he said. “People don’t go there to have powerful discussions. When I go into the Garrick I feel the whole weight of the world is lifted off my shoulders.”

A few members of these clubs will admit that membership has been a useful gateway to influential people. A member of Brooks’s said the claim that no work or networking were done there was “nonsense”. But there is a concerted attempt by Garrick members to downplay the significance of what’s spoken about in the clubs. They generally prefer to portray the atmosphere as closer to Bertie Wooster’s Drones Club, where members while away their time throwing bread rolls at each other. “This is not a place where people are secretly controlling the destiny of the country. Maybe some members were operating the levers of power 10 years ago,” one member, who is in his 40s, told me (adding that “in Garrick terms, I’m a teenager”). He said the club was rather “like an old people’s home with wine”.

Members, serene with the self-confidence of entitlement, cheerfully rub along. “It’s really not about networking. Often I have no idea who the other members are and it’s deemed vulgar to ask what they do,” another member said. “You don’t say: ‘Hello, what do you do?’ I’ll be happily chatting to someone, and then later I’ll discover that they were the master of the rolls.”

The former Telegraph editor Max Hastings, a passionate defender of the institution of gentlemen’s clubs, believes they should be seen as “extremely pleasant backwaters. Modern West End clubs have nothing at all to do with real life in Britain in the 21st century.” This, he said, was what made them appealing. “Because I am old, and I come from a certain tradition, I like the mustiness of clubs. They have such wonderful staff. One is treated like family. Everybody trusts each other totally. Hardly any of us live in stately homes any more, but this is as near as one gets, in terms of having relationships over decades with very nice staff.”

He has appreciated spending time at Brooks’s while researching a book on the first world war. “Brooks’s is the great pre-first world war Liberal club. Every time I sit having lunch in the dining room, I think of those leaders lunching in that same room 100 years ago. One loves that – the weight of tradition.”

I asked if it wasn’t a bit of a shame that female historians writing about the same era couldn’t steep themselves in the same history. “I can’t make a rational defence,” he conceded. “I would fight to the death against discrimination in employment for instance; but clubs, inherently, they are leisure places. If peculiar, quirky old men choose to spend time in the company of each other, so be it.” (However, Hastings said, he would not dream of joining the Garrick “because of its incredible complacency and that horrible tie, all those boring old judges. I’d sooner have my toenails extracted with red hot pincers.”)

He acknowledged that the clubs he visits are almost uniformly white in their membership. “It is the nature of all clubs – whether working men’s clubs, or bowls clubs or gay clubs – is that people choose to gather together in the groups of people they feel comfortable with, and whom they know. You occasionally see a black or brown face as a guest – but very few people of other races are members. I don’t think that is because all members are racist. It’s because we choose to spend our leisure hours with people who are more or less from the same dreary old backgrounds as us.”

It isn’t just Garrick Club members who are impatient with the suggestion that women should be allowed to join. Ann Widdecombe, the former Conservative prisons minister, who was the first female member of the Carlton Club in 2008 when it changed its rules, dismissed the suggestion that all-male clubs are unfair.

“I am a 70s feminist, not a 90s, not a whimpering sort. The current feminism is all about victimhood, and I can’t bear it. It’s not what we were about – the roar that was feminism in the 1970s said: ‘You give us equality and we’ll prove we’re just as good as you.’ By the 1990s, this had diminished to a whimper that said: ‘We’re not making it – we want special privileges.’ That to me is anathema. Feminism to me is going out there and competing with men on equal terms. It’s not having your path smoothed for you. I’ve never had that grievance culture.”

Among those Garrick Club members in favour of reform there is some anxiety about whether they will garner enough votes for the required two-thirds majority in June. One reform-minded member pointed out that earlier this year, a vote on whether women should be allowed to join Oxford University’s elite sports club, Vincent’s, did not reach the two-thirds threshold. Women were told that they had Atalanta, the female equivalent – notwithstanding the fact that Atalanta doesn’t actually have a club house.

Melvyn Bragg, who backs women members, said it was more likely now than in 1991 that the vote would go in favour. “There are many younger members now; we live in a different London; we live in a different world. There has been a sea change in all sorts of things and I think the sea change will come through the doors of the Garrick.”

Bragg said he was occasionally “made to feel embarrassed” at being a member. “If I say ‘Why don’t you come for lunch at the Garrick?’ to some women, they will say no on principle,” he said. “I think it is anachronistic and unsustainable. I would be in favour of it changing tomorrow.”

Even if the Garrick votes to admit women, it will be some time before they are able to join in any number: there is a seven-year waiting list and a current member has to die before a new one can join. Still, time marches on: a board by the entrance to the dining room displays numerous typed death notices. Passing this momento mori, members and their guests go in to enjoy chicken consommé, turbot and thick slabs of beef, selected from a menu unsullied by modern culinary trends.

Follow the Long Read on Twitter: @gdnlongread

- This article was amended on 30 April. An earlier version mentioned the 2010 Equalities Act. It is in fact the 2010 Equality Act.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion